Written by Guest Blogger, Kate Foster

Written by Guest Blogger, Kate Foster

The Avenue is a small, but significant, historically Black community at the end of Crichton Avenue in Dartmouth. Only a handful of Black families live there today, but the community was once home to over 130 residents and spread over a larger area of land, near Mic Mac Mall. The community’s rich history lives on in the experiences and memories of its members, like Carolyn Fowler, who was born and raised in The Avenue. I came to know Carolyn after I was inspired to write a short story set in her community.

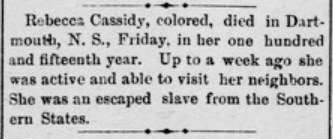

By chance, I had read—in The Story of Dartmouth by John P. Martin [1]—about Rebecca Cassidy, who had lived on the Colored Meeting House Road, now Crichton Avenue. Rebecca was said to have been 115 years old when she died in 1885 and had been born a slave in the United States. I was intrigued and wanted to know more. Rebecca would have been an early member of the Crichton Avenue Black community, of which I had known little, despite living nearby. Both local and US newspapers [2] reported her death, noting her age and that she had escaped slavery in the Southern States. Nova Scotia census records show she was more likely between 92 and 94 years old. But who was she and what was her legacy? Was she related to the existing community?

As a Black person who grew up in an all-white environment, I often sought connections with Black culture through history and stories. I read all I could find about Rebecca, and although a lot was missing, I thought she deserved more than a brief mention in history. I wrote a story about her, [3] set in The Avenue, hoping to highlight Rebecca and add to awareness of this early Black history in Dartmouth.[4]

I was writing fiction but wanted to be respectful and accurate, and I sought out Avenue community members for feedback on the story and having an outsider write about the community. Dartmouth hair salon owner Tracey Crawley kindly put me in touch with Carolyn, and we met soon after. Over many conversations, Carolyn described her family history, which gave me a deeper understanding, helped to expand my story and led to friendship. In the process of researching Rebecca and interviewing Carolyn, I learned interesting facts about the past and present Avenue.

Racism and development

Originally isolated by woods on the outskirts of Dartmouth, The Avenue was subject to the racism experienced by other Black Nova Scotian settlements. There were no municipal services, but town operations were placed there—the stone crusher in the 1930s and the dump in the 1940s. As Dartmouth expanded, including the relatively well-off Crichton Park neighbourhood, the land around The Avenue became increasingly valuable, and the stone crusher and dump were moved. Since then, the community has been gradually surrounded by residential, commercial, and recreational development. Construction of a highway and the Kings Arms apartment complex in the 1970s and, recently, high-rise housing have consumed some of the land once occupied by Avenue residents and hemmed in the remaining, small stretch of single-family homes.

From refugees to landowners

It is hard to determine when settlement in the area started, but one of the earliest known landowners in The Avenue was Rebecca Cassidy’s husband Louis,[5] who, in 1824, bought 8 acres of land from White farmer Henry Kaler (later spelled Keeler) for 8 pounds.[6]

Like Rebecca, many of the community’s earliest settlers were Black Refugees—and their descendants—who had fled slavery in the United States during and after the War of 1812 and came to Halifax on British navy ships between 1813-18. A Halifax newspaper reported that Rebecca arrived in Nova Scotia in 1812; if accurate, she was among the earliest Refugees to Halifax.[7]

Property ownership for Black Refugees soon after their arrival was not common; many lived on land belonging to others or held licenses to occupy instead of land grants. Some Refugees who were first settled in Preston moved to Dartmouth after being unable to farm nonarable land.[8] After her husband’s death,[9] Rebecca owned the 8-acre piece of land until 1880, when she sold it for $150 to a White accountant and civil servant named Louis Parker.[10] She continued to live in The Avenue until her death 5 years later.

Original families and endurance

Later Avenue residents often came from downtown Dartmouth and nearby Black communities, moving in for work or family. Descendants of at least five long-term families still live in The Avenue, evidence of the strength of the community despite nearly 200 years of racism, discrimination, and neglect.

A descendant of early residents, Carolyn is one of few Black elders living on land that has been in her family for at least four generations. Carolyn’s family tree—through a Tynes relative—might even extend back to Rebecca Cassidy. As a widow, Rebecca was the head of a Tynes family in The Avenue. An active and thoughtful 80-year-old, Carolyn is proud of her ancestors’ resilience: “We weren’t meant to survive…. Many built good lives for themselves, learned trades, worked, built property…. They paved the way through their perseverance.”

Black and proud

When Carolyn was growing up, it was “an all-Black community, at the edge of the city, without water, without sewer, without paved roads. The incinerator was here. People didn’t have deeds to their property.” Carolyn only became aware of the stigma imposed on the community when she was older. “We didn’t live by the dump, they put the dump beside us.”

Yet for Carolyn, The Avenue of her childhood was idyllic. “Dartmouth was the city. We were in the country. We were surrounded by trees and greenery.” The Avenue was filled with lilacs, fruit trees and blueberries. She learned to swim and skate at Lake Banook. Life in the tight-knit community was positive, stable, and loving. Neighbours watched out for and helped raise community children. Church was mandatory, and there was always music, laughter, and camaraderie. Family and neighbours often gathered in her parents’ kitchen to sing and banter about community politics. Her upbringing in The Avenue created life-long friendships and strong feelings of belonging and pride.

Hard work and life lessons

Carolyn’s parents and other community members emphasized education and hard work, values that enabled her “to live a quality life.” Her father, a CN railway porter on the Halifax-Montreal route, became bilingual, a service instructor and union leader. Her mother, Vivian, raised Carolyn and her sister Joanne and was the family “glue” and caregiver. Vivian also worked part-time as a domestic for White families, work she “hated,” but was common at a time when opportunities for Black women were extremely limited. Carolyn earned a Master of Education and was among The Avenue’s first university graduates. Many from The Avenue had successful careers in the military and government, as actors, entertainers, and private sector professionals.

A childhood lesson from her mother is still vivid in Carolyn’s memory. One day, her mother sent her on an errand to buy something at Lynch’s store on Crichton Avenue. While there, Mrs. Lynch said to Carolyn, “When you get home, tell your mother that I’m looking for someone to do housecleaning. Does she know anyone?” Carolyn returned home and told her mother, who replied indignantly, “You go right back down to that store and tell Mrs. Lynch I’m looking for someone too.” Carolyn did as she was told and, years later, admired her mother’s quick-witted response.

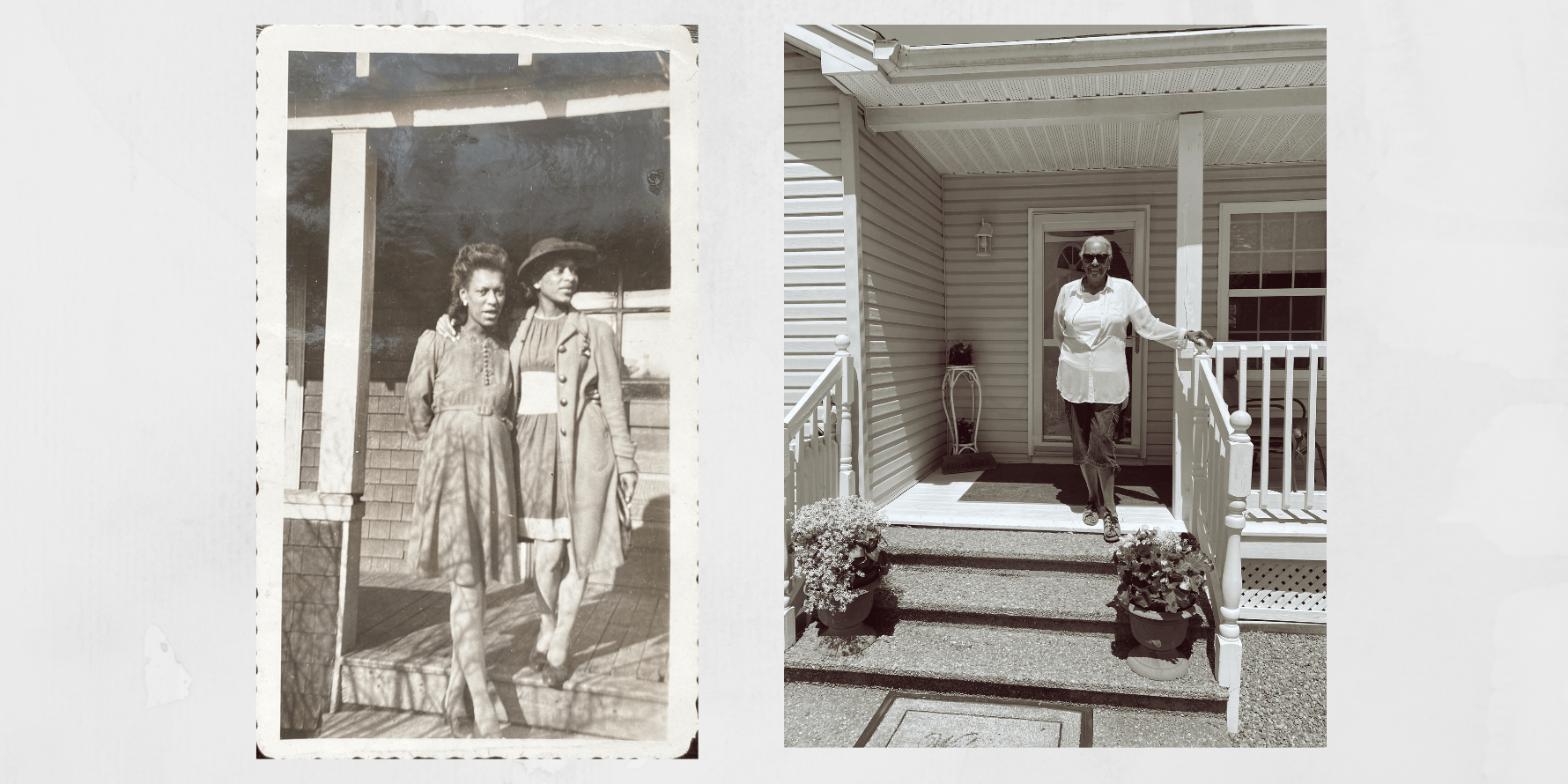

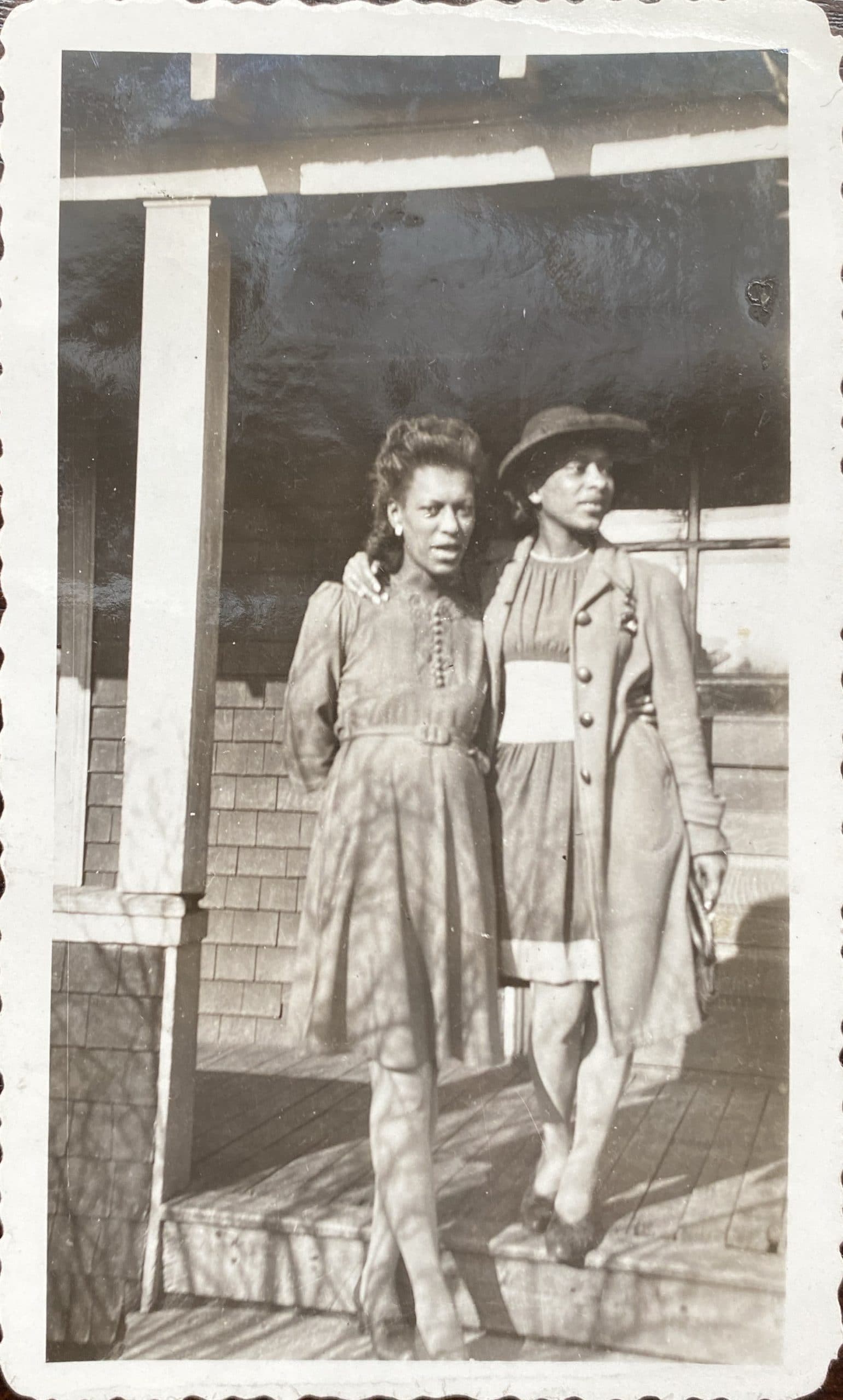

The Fowler-Samuels homestead

Carolyn’s roots in the community are deep. She grew up in the house at 238 Crichton Avenue, built in 1921 by her grandfather Wilfred Samuels. Born in Antigua, Samuels was a railway porter who married Edith Bauld. Both Edith’s parents and grandparents lived in the community and were married at the African Meeting House, The Avenue’s first church and the centre of community life. Carolyn’s father, Frank, bought the house at 238 from her grandmother Bauld, ensuring it would stay in the family.

Except for a few years in Halifax, Carolyn lived in The Avenue until she was married. She later returned to care for her mother, eventually building a new home on her mother’s land in 2005. Her mother—who had always kept her house well-maintained—agreed to move into the new house with her, as long as Carolyn promised the old family home would be preserved and not torn down. At the new house, which overlooked the old one, Vivian would sit on the veranda and tell stories about her youth and experiences in The Avenue. “It was a mini history course,” and Carolyn treasured those times with her mother.

Early beginnings: The Church and Reverend Preston

The oral history passed on by Carolyn’s mother included her always saying there had been two church buildings in The Avenue. Property records confirm there were two early churches. Sadly, both were destroyed by fire.

The Avenue church, where Carolyn’s great-grandparents were married in 1887, was officially organized in 1844 by Reverend Richard Preston. This Dartmouth church was a branch of the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church (now New Horizons Baptist Church), founded in 1832 and the Mother Church of the African Baptist Association of churches, both established by Reverend Preston.[11]

Prior to this, however, residents of The Avenue had been gathering to worship, and Reverend Preston had helped found a small meeting house in the community. In 1827, Trustees of the African Baptist Church in Dartmouth—Jacob Allen, Richard Preston, and James Slaughter—bought land from Henry Kaler for 5 shillings. This was the same Kaler who had sold land to Louis Cassidy three years earlier. According to the Trust Deed, Kaler sold the land, in part, due to his “wish that a Church or religious House of worship upon the principles of the Baptist faith should be established at Dartmouth… among such people of colour as may hereafter become Members of the said Church.”[12]

The first Pastor of this Church, Preston was a charismatic preacher who attracted large congregations and converted many in Dartmouth. Rebecca Cassidy—a founding member— would have been among the first worshippers listening to Reverend Preston. Close in age, Preston would have followed a similar path as Rebecca; he was born a slave in Virginia and arrived in Halifax about 1816.

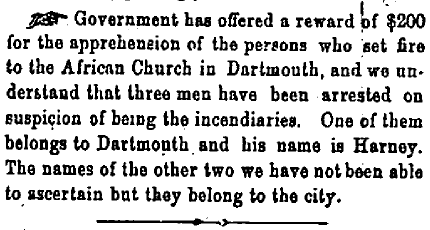

In 1865, arsonists set fire to the original Church. Three men were arrested, but it is unknown if they were charged.[13] After the Church was burnt down, another location was selected to build a new Church, and Trustees of the Church sold the land that the original Church had been situated on back to Henry Kaler’s son William in 1869 for $40. [14]

The second African Meeting House burnt down in 1896, and for almost 10 years the community did not have a designated place of worship; despite this, the congregation continued church activities. In 1905, the Anglican Christ Church in downtown Dartmouth donated its old Sunday school building to the community. The building was moved to Victoria Road, became known as the Victoria Road United Baptist Church, and continued to serve The Avenue and its extended community.

The community was never officially named, but the Church, the road leading into the community, and the land were referred to by many names over the years: the Black Settlement, African Meeting House, African Baptist Church, First Lake Road, Dartmouth Lake Church, the Colored Peoples’ Meeting House, Colored Meeting House Road, the Colored Walk, Tynesville. In 1894, the street was named Crichton Avenue and the community came to be known as The Avenue during Carolyn’s youth.

Hardship and the fight for rights

Both the early and later Avenue often faced hardship. Its placement outside of town meant residents had to walk long distances for work and to access services. The Church provided Sunday school, but the early community did not have access to a school for their children.

In 1836, Rebecca’s husband Louis Cassidy—a farmer—and other Black residents petitioned the government for a school for Black children in Dartmouth. The request was ignored, and it wasn’t until 1879 that the segregated Colored School opened for Black children near the Dartmouth Common. After it closed in 1915, Black children in the area attended White schools.

Recalling her own school years in Dartmouth, Carolyn says the integrated experience gave her “more exposure and opportunities,” but also underscored the separation of her community: “I had White friends while in school, but no interaction after school.” The walk back and forth to school several times a day, however, created unity with her Avenue peers.

Early community members, like the Cassidys, established a precedent of fighting for basic civic rights, a practice continued by later residents like Carolyn and her father. Frank Fowler fought for water and sewer for the neighbourhood, insisting he was entitled to these services as a taxpayer. The Avenue only got running water in 1963 and a sewage line in 1986. It took until 1988 for the dirt road through the community to be paved.

Property issues

As a railway porter for 35 years, Frank Fowler had more financial security than some in the community. Some residents were boarders, others were squatters. Many had title issues for their land. Inconsistencies in property descriptions and boundaries were common. Carolyn’s father sometimes paid the property taxes for others who could not afford to.

Frank Fowler taught Carolyn the importance of property ownership and made sure the family had a deed for their land. In 1985, some Avenue residents hired African Nova Scotian lawyer Wayne Kelsie to obtain clear title to their land from the city. Residents pursuing proper title finally led to the city extending the sewer line and The Avenue road being paved.

Gentrification

During the growth and development of Dartmouth, some residents of The Avenue did not profit from having their own land. “They weren’t forced off their land like people in Africville,” says Carolyn. “At the same time, people were getting older, their land was getting harder to maintain and they were taken advantage of.” Pressured to sell and their land undervalued, some Black families eventually sold to developers without much financial gain.

Despite demographic changes in the community, Carolyn says “fragments of the inequality” remain. The only sidewalk in The Avenue ends in front of her mother’s old house, and it was neglected repeatedly by city plows over the years, despite sidewalks across the street in Crichton Park being plowed. Carolyn often called the city to make sure the sidewalk and roads through The Avenue got plowed. Sometimes, a neighbour’s garbage collection is still forgotten. It is a carry-over, Carolyn says, of past discriminatory treatment of the Black community by the city.

Burial grounds

A more painful part of The Avenue’s history is the loss of ancestral burial grounds. Avenue residents were buried in the community until the early 1900s. The location of the graveyard is now uncertain and there may have been multiple burial sites over the long history of the community. Graves were found during excavation in 1976 for the Kings Arms apartments. Some remains were removed and buried at the Christ Church cemetery, near the Victoria Road United Baptist Church. Carolyn thinks it is likely there were other graves in the community that were built over and lost.

The Avenue today

In 2020, the city acknowledged The Avenue in a small way by posting a sign describing the community at Birch Cove by Lake Banook, about a kilometre away. Although pleased to see some recognition, Carolyn questions why the sign was not placed directly in the community. She would like to see the community’s history honoured in a more significant and prominent way, including an acknowledgement that Black people from The Avenue helped build Dartmouth, with their work as farmers, labourers, tradespeople, entrepreneurs, and professionals.

With fewer Black people living in The Avenue, sometimes there is the perception that Black people don’t belong in the area. Despite the smaller numbers, Carolyn says she is part of “a broader Black community… and that positive Avenue feeling stays with me.” Carolyn remains a guardian of her ancestors’ land and history. Her personal legacy is also significant. She raised two daughters, has seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Her first great-grandchild was born when her mother was still alive, and five generations were able to gather and celebrate in The Avenue. Living on her family homestead, Carolyn says, “I’m where I belong, right where I started.

Citations

[1] John P. Martin. The Story of Dartmouth. (Self-published, 1957).

[2] Morning Herald (Halifax) May 11, 1885; Evening Mail (Halifax) May 9, 1885; Staunton Spectator (Virginia) May 13, 1885; Star and Sentinel (Gettysburg, PA) May 12, 1885; Philadelphia Record, May 9, 1885; Springfield Daily Union, (MA) May 14, 1885; Paterson Daily Press, (NJ) May 9, 1885; National Tribune (Washington, DC), May 14, 1885.

[3] “African Meeting House.” Augur Magazine 4.1, November 2021. http://www.augurmag.com/african-meeting-house/

[4] For more history on The Avenue, see Adrienne Lucas (Sehatzadeh). “Survival of An African Nova Scotian Community: Up the Avenue, Revisited.” (1998).

https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/tape15/PQDD_0012/MQ36526.pdf

[5] In various historical records, Cassidy was often spelled Cassedy, Cassady or Casidy and Louis was often written as Lewis.

[6] Halifax County Deed Book 48, Page 57 (H. Kaler to L. Cassedy, 1824). Henry Kaler, of German background, moved to Dartmouth about 1801 (Martin, History of Dartmouth, 131). According to the Census Return of 1827, he owned 10 acres in Dartmouth. He and his wife Elizabeth had a large family; many of their descendants built homes and owned property along Crichton Avenue on what was once their land.

[7] Evening Mail (Halifax) May 9, 1885.

[8] Harvey Amani Whitfield, Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1860. (Burlington: University of Vermont Press, 2006).

[9] Louis Cassidy’s date of death is unknown. He is listed as Head of Family in the 1851 Census of Canada East, Canada West, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Rebecca is listed as Head of Family in the 1861 Census of Canada and was likely a widow by this time. In the 1871 and 1881 Censuses of Canada, Rebecca is listed as a widow.

[10] Halifax County Deed Book 225, Page 266 (R. Cassedy to L. Parker, 1880).

[11] Minutes of the Session of the African Baptist Association (Granville Mountain, September 1855).

[12] Halifax County Deed Book 50, Page 15 (H. Kaler to J. Allen and others, 1827). Henry Kaler, also Baptist, was involved in the establishment of the First Baptist Church in downtown Dartmouth that served White Baptists in the area.

[13] Halifax Citizen, July 22, 1865. It is assumed the arsonists were White men, since Black people, when reported, were almost always identified by their race, as “Coloured,” “African,” or “Black.”

[14] Halifax County Deed Book 165, Page 550 (African Baptist Church Dart. to W. Kaler, 1969).

About the Guest Blogger

Kate Foster is a Black Nova Scotian whose writing has appeared in Augur Magazine, filling Station, Understorey Magazine, Canthius and Room Magazine. She lives with her family in Dartmouth, NS.

Add a comment to: “Where I Belong”: Tracing the History of Dartmouth’s ‘The Avenue’