Written by Vicky and Amy, staff members, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window, with help from special guest, Elena Cremonese, Halifax Municipal Archives Technician

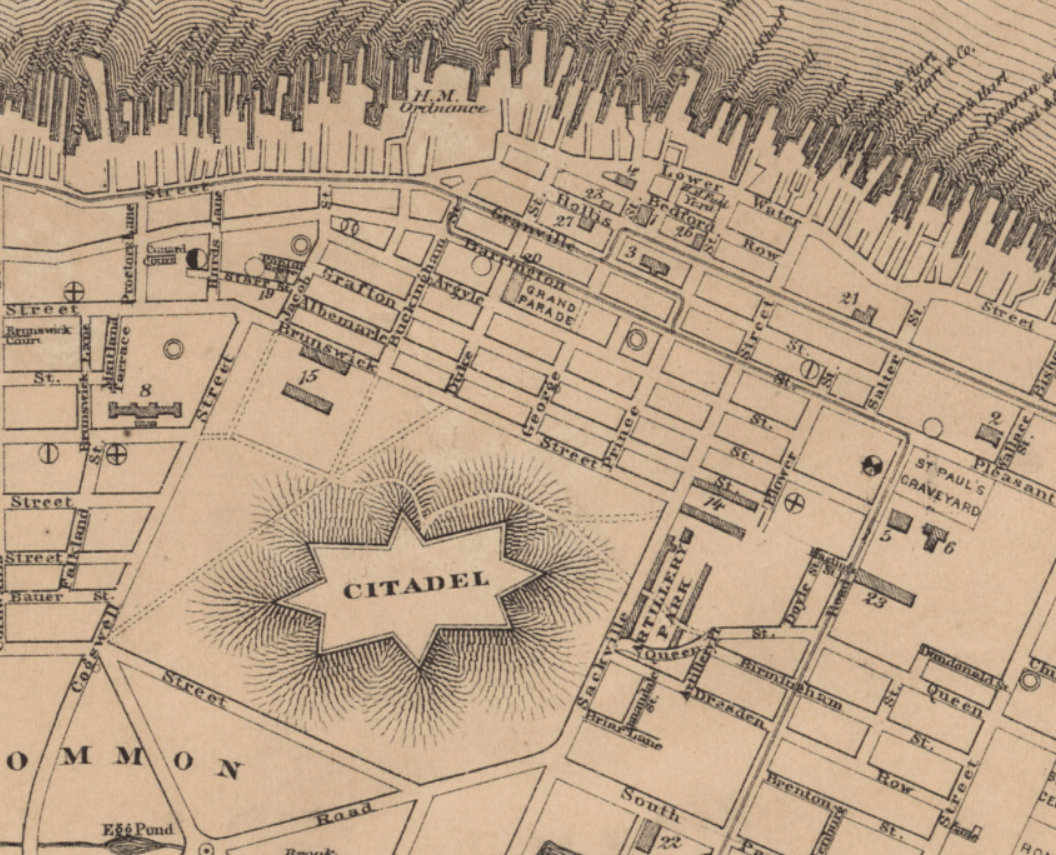

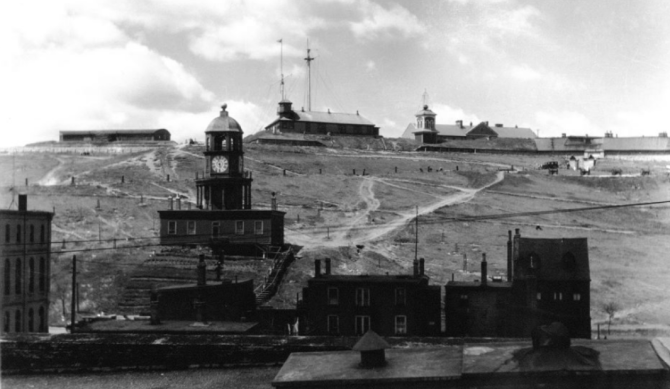

“Persistent Fairy Tales”—that is how The Mail-Star referred to the legend of the Halifax tunnels in 1973. More than 40 years later, Tim Bousquet of the Halifax Examiner agreed: “Every place I’ve ever lived has myths of 'secret tunnels' running under the town, and Halifax is no different… And to George’s Island?... There is no way people in 18th or 19th century Halifax would even seriously contemplate such a project, never mind successfully completing it, and in secret no less. That’s just delusional” (2015). Delusional or not, rumours of mysterious, underground passageways that lead from Fort George on Citadel Hill to various locations across the city have remained prevalent for decades. So the question is: do these myths have merit? Let’s take a look at the facts and the fiction about our famous tunnels.

Precedence and possibilities

The British have a bit of a love affair with tunnels.

In fact, this love is so well known that Hal Thompson, a Visitor Experience Officer at the Citadel through Parks Canada, referred to their construction as a “common feature of… defence networks” in British towns (Underground Halifax, 2015). Fort Southwick, for example, was one of several forts used to defend the Portsmouth, UK naval base. It has four underground tunnels dating from around 1860. In the 20th century, further underground construction allowed for oil pipelines, bomb shelters that could hold up to 5000 people, and a radio station. Devonport, UK also has underground passageways that date as far back as the Napoleonic War.

And it wasn’t just the government building tunnels. In Liverpool, UK Williamson Tunnels run under the Edge Hill area of town. They were built in the early 19th Century by tobacco seller Joseph Williamson, but no one knows exactly what purpose they served.

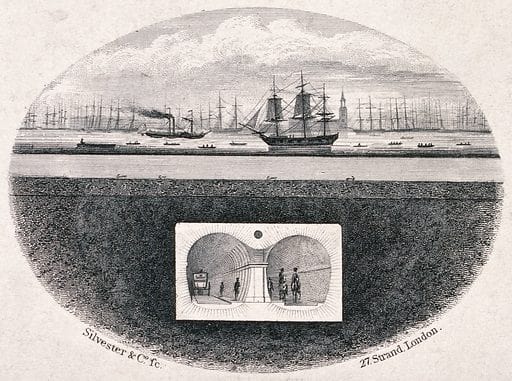

With this in mind, it is of little surprise that people might be inclined to think that the British brought their love of tunnels with them to Nova Scotia. Of course, building an underground tunnel is one thing; building an underwater one is quite another. The idea of a tunnel that leads from Citadel Hill to George’s Island seems nearly impossible, even by today’s standards. The complex engineering needed to build a passage under the water would be incredible, especially in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. And yet, starting as early as 1820, the British found themselves attempting such a feat.

In the early 19th century, London was a bustling port city that was running into a big problem—traffic jams. One of its major trade routes, the Thames River, had grown so congested it was becoming difficult for goods to get through. The government and private citizens alike examined many solutions, such as building additional bridges across the river, but this was not possible as they would block water access to larger sailing vessels. Out of desperation, they began to think outside the box and looked toward going under the river rather than over it.

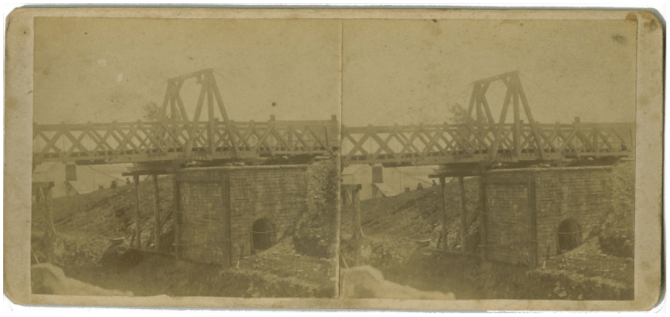

Several people made attempts to build a tunnel under the Thames with little to no success. Cave-ins and floods were a regular occurrence, and the financial burden of the project was more than entrepreneurs could bear. However, in 1825 French engineer Marc Brunel invented what he called a tunnelling shield: a device made of iron that would support the face and roof of the tunnel to keep it from collapsing. Men would dig out the front of the passageway, move the shield forward, and masons would follow the shield, laying brick as it advanced. This technique was not without risks; it was dangerous work, and several miners lost their lives. In fact, after 6 men died in 1827, the tunnel was temporarily abandoned. But Brunel would not be deterred, and seven years later he convinced the government to give him the financial support he needed to continue. The tunnel was finally completed in 1841 at a total length of 366 metres. For Halifax, this means that a tunnel to George’s Island was at least theoretically possible.

The other big question about all of this tunnelling is: where did the dirt go? Surely, if these vast secret tunnels were being dug in Halifax, there should be historical records mentioning the cartloads of earth and rock being moved from one place to another. How would they hide it?

Well, they might not have needed to.

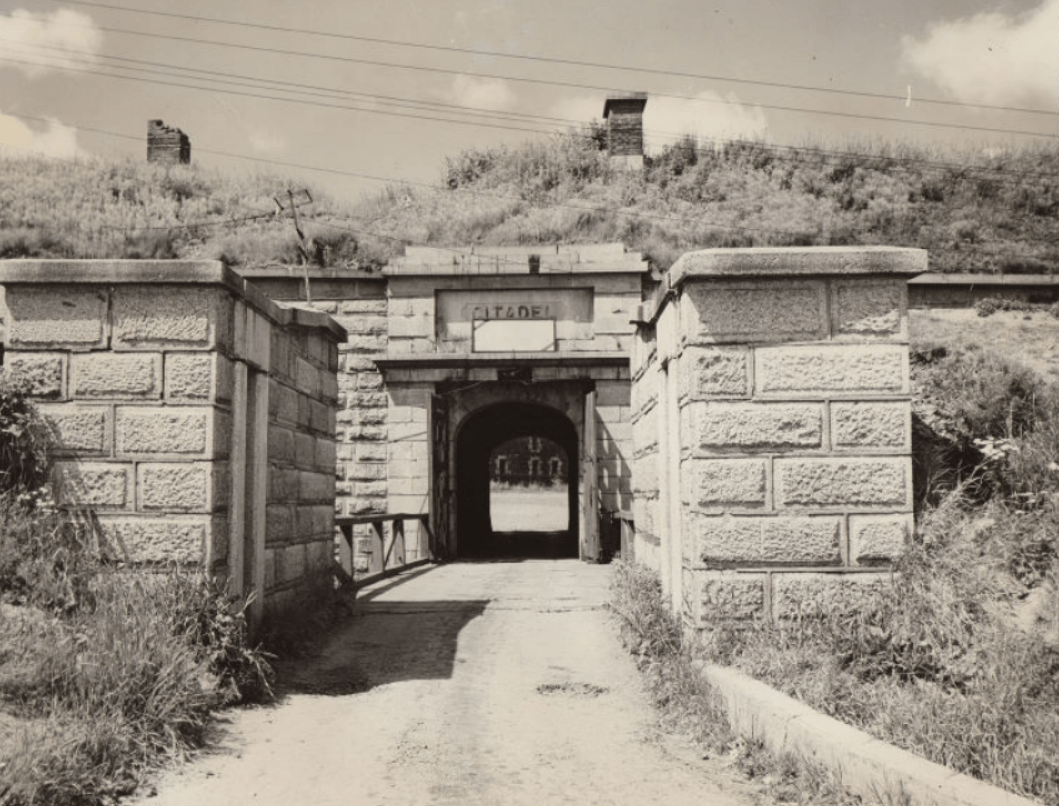

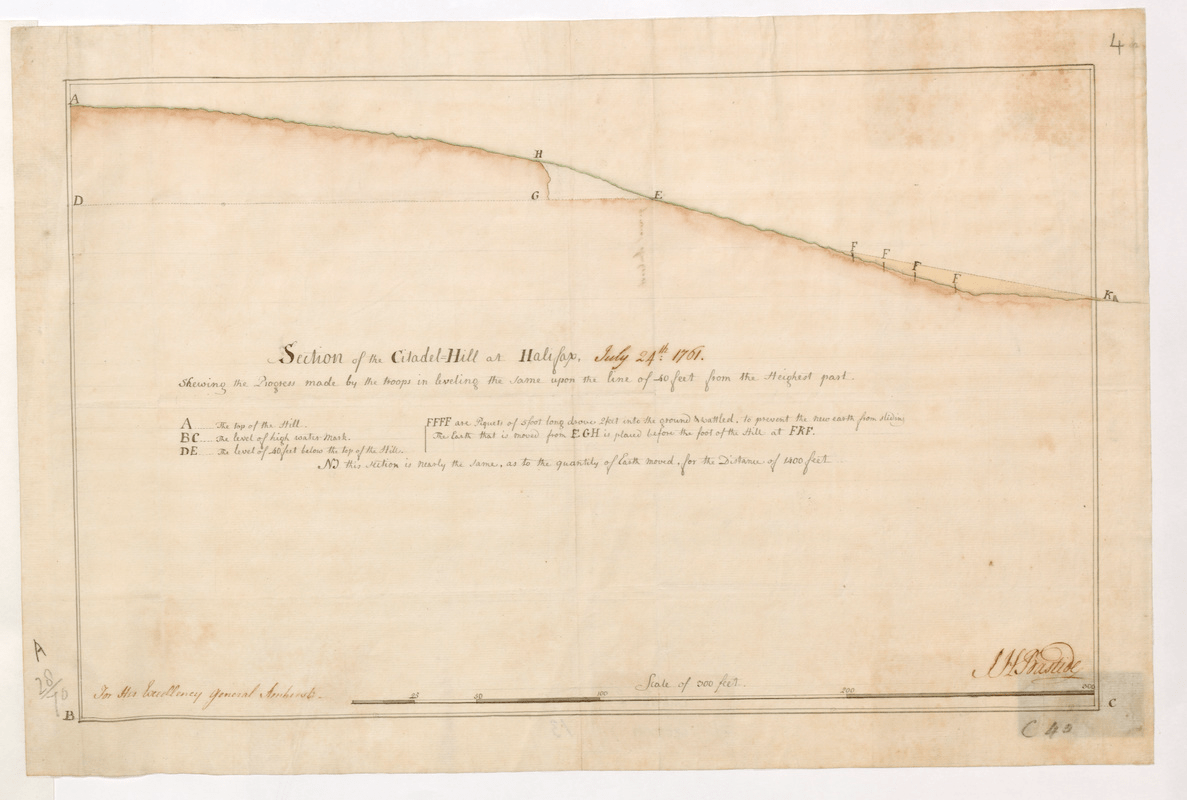

Remember that in the 18th-19th century Halifax was very much a city on the rise. Just like today, new construction projects were the norm, and in all likelihood, it would have been very common to see carts of dirt being moved from one place to another. The Citadel specifically went through many changes. The first version of Fort George built in 1749/1750 was made of wood and needed to be rebuilt on two separate occasions. Plans for the stone fort we know today were drawn up around 1825 and were completed in 1855/1856.

One of these rebuilding efforts involved removing significant amounts of earth from the top of the hill in order to level the ground. With this much dirt moving around, who would notice a little more?

Facts are facts

The truth is: there are tunnels under downtown Halifax and Citadel Hill, and we have the receipts to prove it.

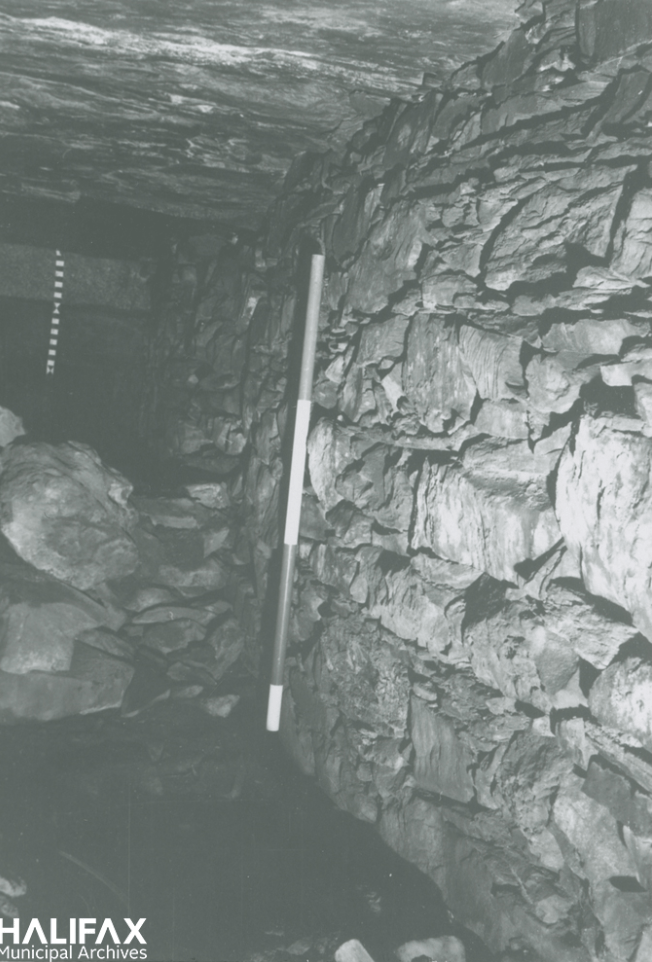

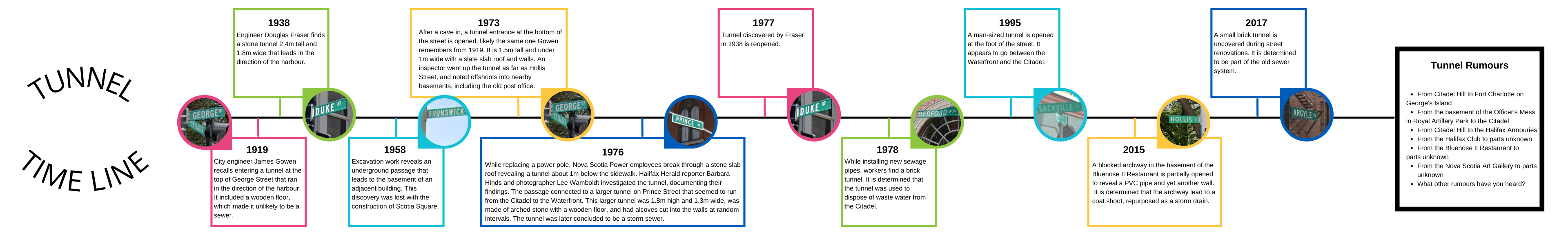

James Gowen, a city engineer, recalls entering a tunnel at the top of George Street in 1919. He stated that the tunnel ran in the direction of the harbour and had a wooden floor. To him, this implied that the tunnel was used for the movement of people, rather than something like a sewer, or other city services. This passageway was confirmed again in 1973 when a cave-in at the bottom of George Street opened the tunnel from the opposite end. At 1.5 metres tall and 1 metre wide, it was easy for a person to enter and walk through it. A city inspector did just that, walking up as far as Hollis Street before turning back. While in the tunnel, the inspector noticed secondary tunnels that looked like they once connected to nearby buildings, including the old post office—now the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

In 1938, engineer Douglas Fraser discovered a stone tunnel under Duke Street. This tunnel was 2.4 metres tall and 1.8 metres wide. It also went towards the waterfront. Like the George Street tunnel, this was also rediscovered in the 1970s.

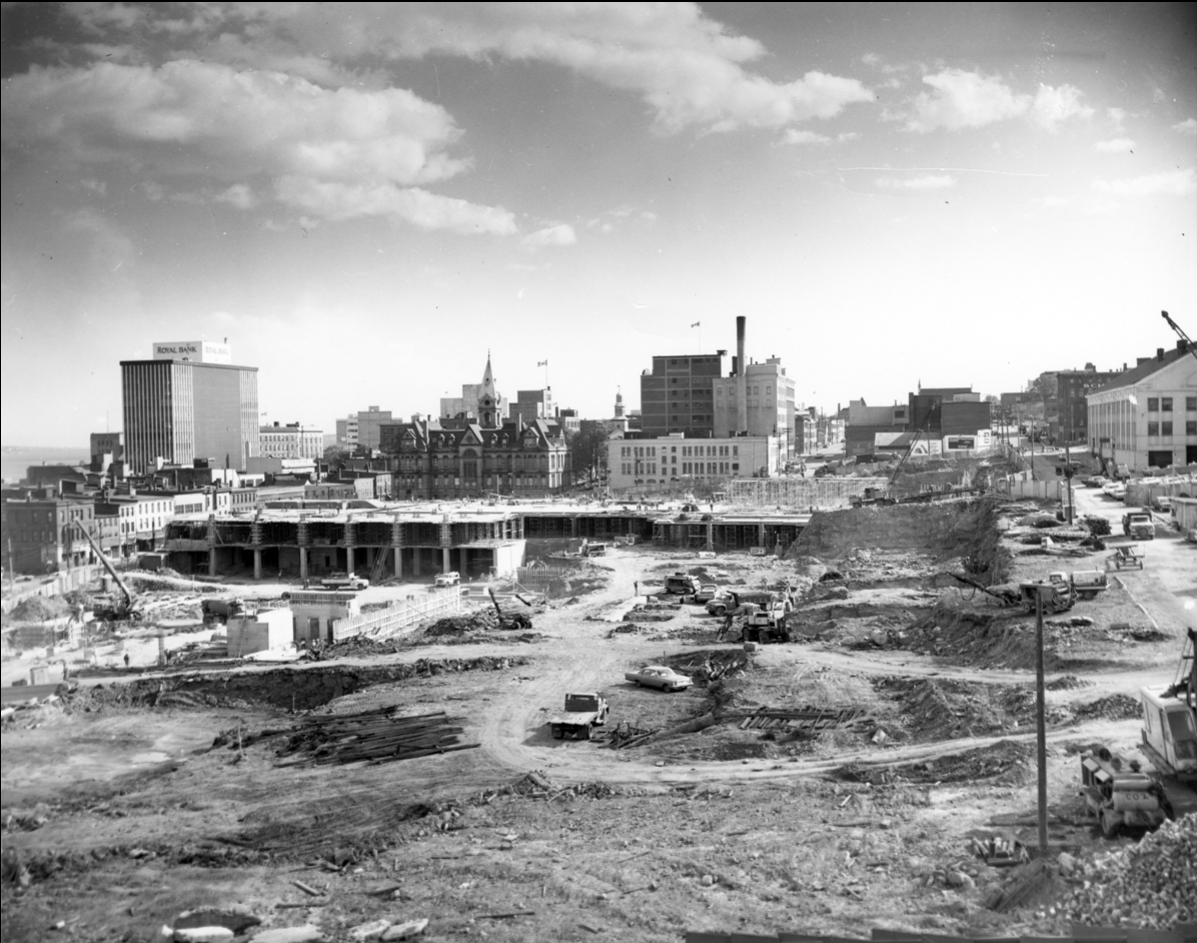

While conducting excavation work in 1958, construction workers uncovered a passage under Brunswick Street. This tunnel also looked like it went into the basement of an adjacent building. This discovery, or what remained of it, was likely destroyed with the construction of Scotia Square.

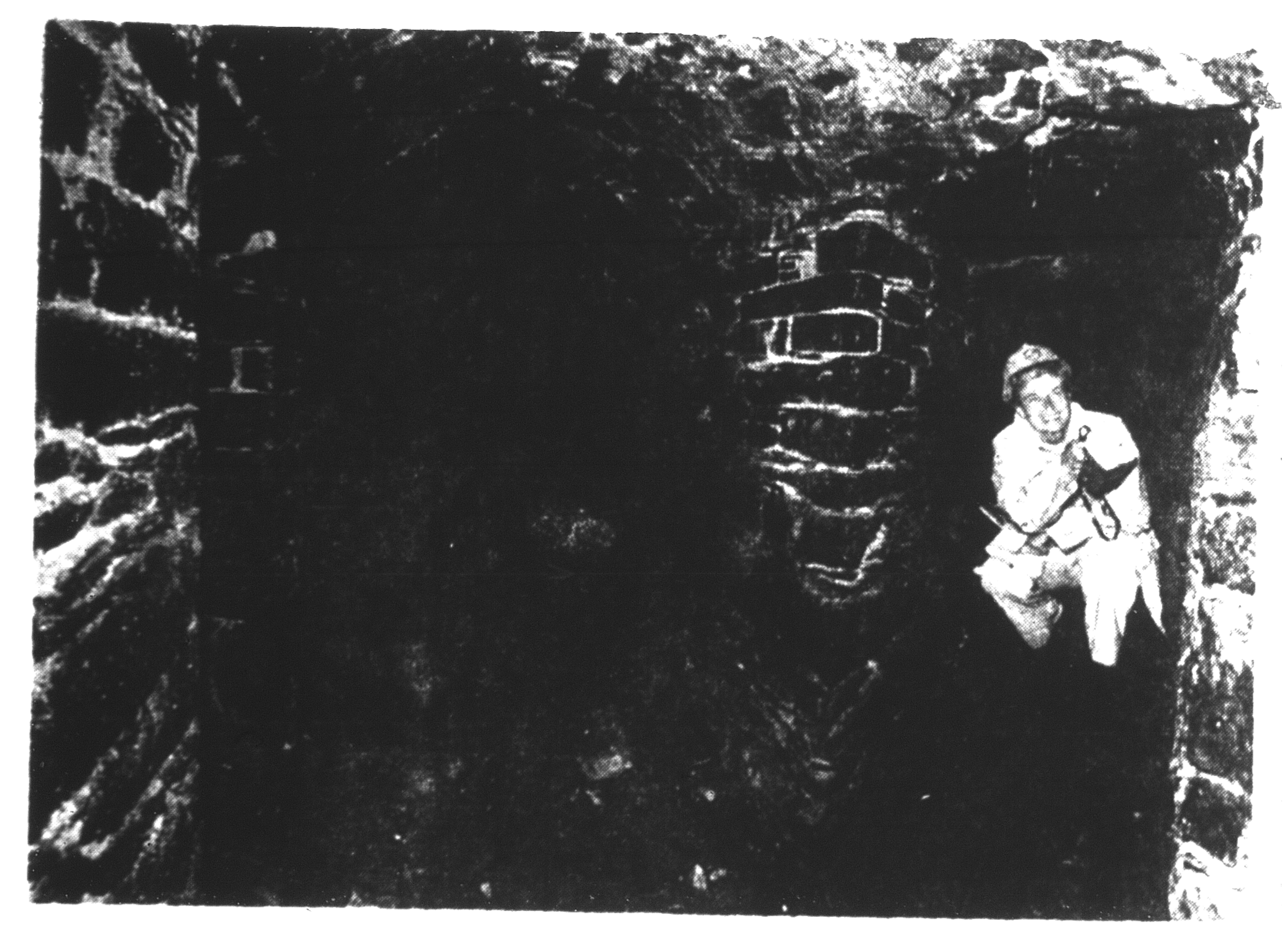

In 1976, another tunnel was discovered under Prince Street. While replacing a power pole, Nova Scotia Power employees broke through a stone slab revealing a small hidden tunnel that lead to a larger passageway. Halifax Herald reporter Barbara Hinds and photographer Lee Wamboldt were on the scene. They entered the tunnel and documented their experience with photographs and a write-up for the paper. “There’s nothing like a trip down an underground passage to brighten up a Monday morning,” Hinds wrote, “The stone fabric and structure appear to be as sound today as the year the masons built it, except where the walls had been disturbed by workmen of more recent times having cables and pipes across the tunnel.” The larger tunnel was 1.8 metres high and 1.3 metres wide with alcoves carved into the walls at random intervals. Like the passage on George Street, it too had a wooden floor.

Several other tunnels were discovered over the years. In 1978 while installing new sewage pipes, workers uncovered a brick tunnel on Bedford Row. A similar discovery was made again in 2017 on Argyle Street. A man-sized tunnel was found under Sackville Street in 1995 that appears to run between the Waterfront and the Citadel.

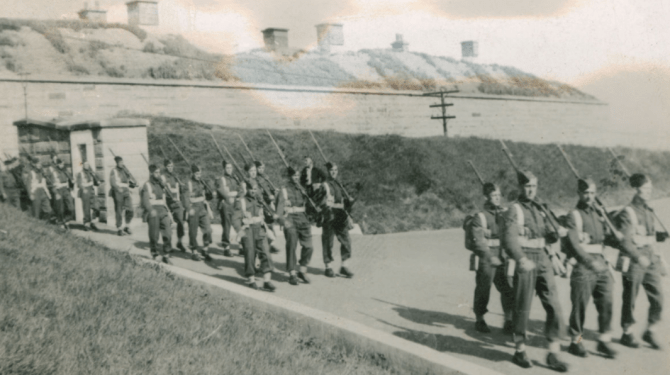

As for Citadel Hill itself, during the 1970s several small tunnels were found during restorations; they lead from the inside of the Fort out into the hill.

So, does this mean that the legends we know and love are true?

Not exactly.

Removing all the fun

A key component of the Halifax tunnel folklore is that the passageways that ran under the city were designed by and for the military. They were kept secret because they were meant to be used as avenues of escape in the event of invasion at Citadel Hill, or at the very least as a way to quickly transport soldiers from one area of the city to another. The problem is that none of the tunnels that have been discovered can be officially traced back to Fort George. The passages found under Sackville, Prince, George, and Duke Streets—while leading up and down the hill seemingly between the waterfront and the Citadel—have never been followed to their official ends. Tragically, in many cases this might not even be possible now due to modern construction and city works projects. For example: in 2015, Archaeologist Laura De Boer teamed up with Halifax Water to scope out what might remain of a tunnel under Duke Street. In the 1990s, a Halifax Water project to replace sewer lines left behind a sketch of an arched formation under the street, but left no indication regarding its size, or whether or not it had been preserved. A robotic rover, armed with a video camera, was sent underground to investigate, but no evidence of older construction could be seen.

Archways found in the basements of certain downtown buildings have also been investigated with disappointing results. De Boer and a stonemason tapped into a bricked-up archway in the basement of the Bluenose II Restaurant (formerly the People’s Bank), only to find a bad smell, the open end of a PVC pipe, and… another wall. De Boer believes that the archway once lead to a hole in the sidewalk outside the building that was used for bringing in coal, or other fuel. When this was no longer needed, the archway was closed, and the opening in the sidewalk was repurposed by the city as a storm drain.

Rumours have circulated for years about a tunnel opening in the Halifax Club that leads to parts unknown, but this gossip has a similarly unsatisfying story. The Halifax Commoner produced a video report in 2013 showing a trapdoor on the floor of the Club that leads to a crawlspace. This crawlspace then connects to a larger ironstone tunnel that is big enough for a person to stand upright and travel with ease. Believed to have been constructed along with the original building around 1861, the tunnel runs for about 50 feet along the north side of the structure and ends in a small room under Hollis Street. The video stated that the tunnel would have been used by servants and staff to bring supplies into the Club’s kitchen. The report also points out that the floor with the trapdoor is not original to the house, and would have been added sometime later to cover the entrance.

Interesting? Absolutely!

A secret military tunnel? Unfortunately not.

The larger tunnels under our downtown streets are also a bit of a legend letdown. De Boer states they are what remains of the old sewer system; the smaller brick-lined shafts are likely just as access points. When asked about the wood floors, De Boer shared: “…I actually have engineering plans from the 1860s that show sewers being constructed with wood bottoms. It’s just the way they were built.”

Similarly designed tunnels have also been found in other cities. For example, Ybor City, Florida has underground passages that date as far back as the late 1800s. Their town folklore says that the tunnels were built by smugglers to transport illicit goods. The passages are described as being “five foot tall and just as wide… a ceiling made up of three layers of bricks with a flat wood floor” (Guzzo, Dec 2018). Sound familiar? While the tunnels may have been used by smugglers at one point in time, they were not built by them; they were government constructed. When a walled-off portion of a tunnel was opened, researchers discovered both 19th and 20th-century pipes and plumbing. The fact is that it was once an active sewer that had simply been forgotten.

As for the tunnels under Citadel Hill, it turns out that they are mine galleries, also known as T-Galleries (referring to their “T” shape). They are around 4 feet tall and extend approximately 20 feet into the hillside. They were designed to be filled with gunpowder kegs that could be lit with a long fuse to blow up the ground beneath any invading enemies. However, none of these tunnels leave Citadel Hill; ultimately they are all dead ends. In 2015, Thompson said: “You can see how people might think it goes somewhere. If you didn’t follow the entire thing, you might be fooled into thinking it goes somewhere than just around the fort.”

If there were tunnels from Fort George out into the city, it’s possible that they—like the coal chute outside the Bluenose II Restaurant—were repurposed. When the Citadel was decommissioned by the government in the 1950s, it was modernized with new washrooms, electricity, and, in the more modern era, the internet. It is possible that a once-secret passage was altered and reused to make room for these modern amenities.

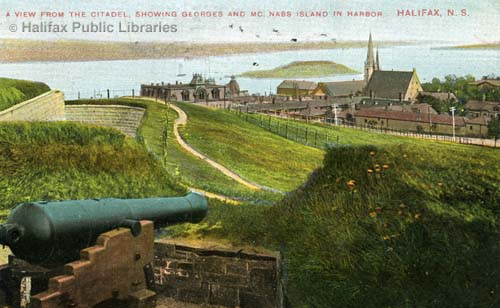

But what about the tunnel to George’s Island? Well, it doesn’t look like we’ll be walking under the sea to George’s Island any time soon.

Thompson has spent years looking for passages at the Citadel but has yet to find evidence of an entrance: “I have no idea where it is. I’ve never been able to find the entrance to this tunnel, whether it was bricked over during the restoration or not. I have spoken to historians who say they have no idea where this thing is either.” Putting aside the difficulty of actually finding the entrance to a secret tunnel, there is a point to be made about practicality.

Although the technology for an underwater passageway was available starting in the mid-1800s, the probability of success in building one—especially in secret—was not good.

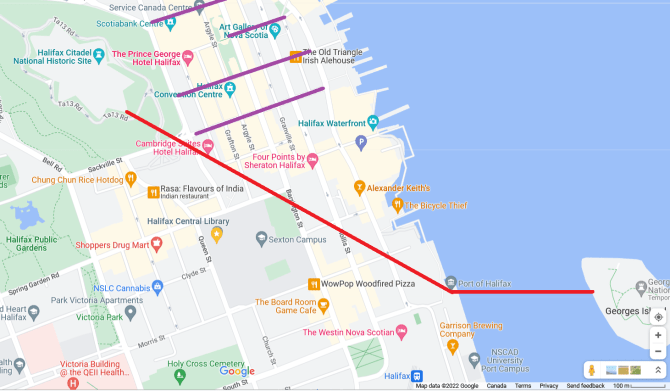

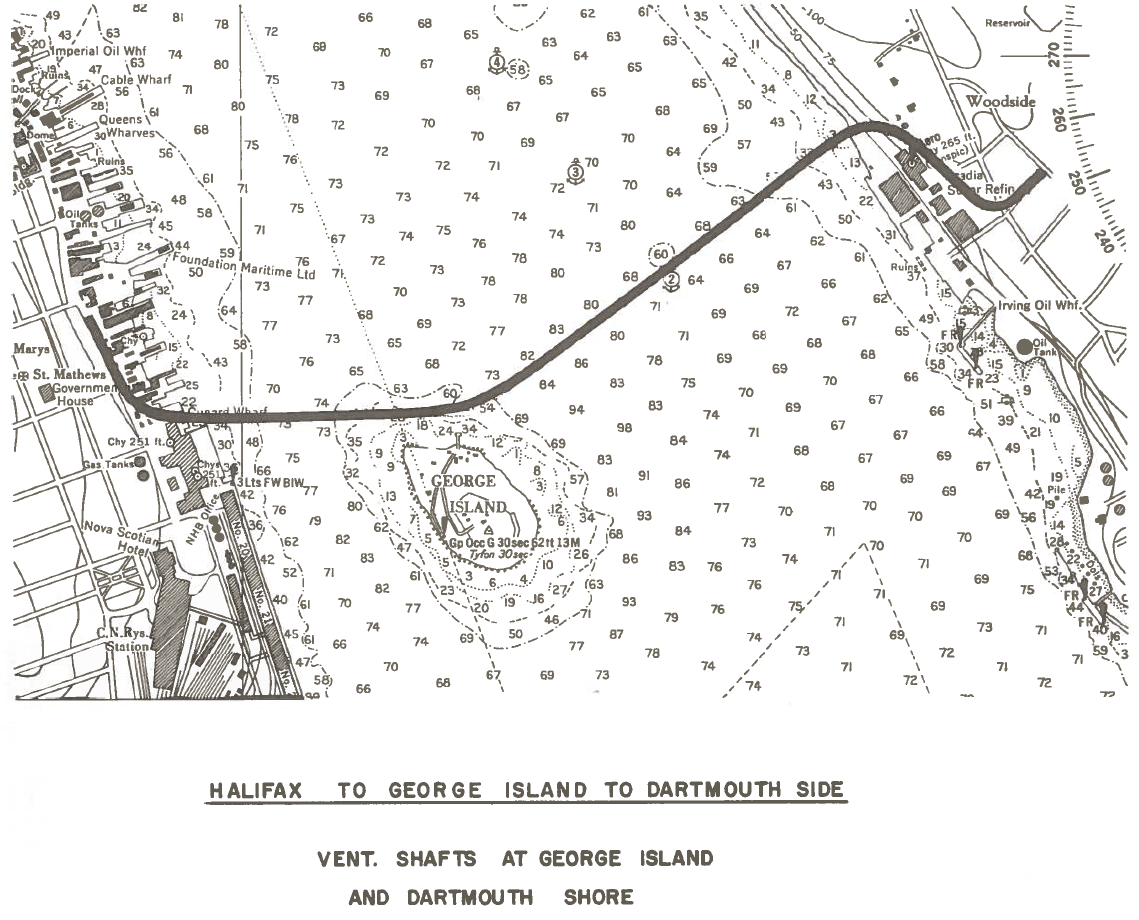

A tunnel to George’s Island from Citadel Hill would have needed to be at least 3100 metres long, with approximately 850 metres under the water. This is assuming the route of the tunnel would be as pictured on the above map, with as little underwater digging as possible. In this case, the underwater portion of the tunnel would be more than twice as long as the Thames Tunnel; that project saw multiple workers die even after invention made the work “safer.” It should also be noted that the tunnels that have been discovered under the city do not line up with this pathway, and would result in considerably more underwater digging.

Whatever the distance, a passage of this size would have taken a very long time. Ignoring the years when the project was abandoned, the Thames Tunnel took approximately nine years to complete. The idea that this project could be done in Halifax at this time in history without any reported loss of life and in secret is extremely doubtful.

In 1990, in an effort to finally put the tale of the George’s Island tunnel to rest, The Bedford Institute of Oceanography performed seismic reflection studies with ground-penetrating radar that mapped the entirety of Halifax Harbour. If there was ever a passage to the island or even an attempt at one, they would have found disturbances in the seafloor to account for it. Unfortunately, no evidence was found.

So, despite all of this evidence, why does the legend continue to persist?

The town scuttlebutt

Like all good myths, this story leaves room for doubt.

In the 1860s, a master mason from Pictou County named John William Cameron was hired by the Royal Army for a contract. According to Cameron’s family, he never discussed his work in Halifax —he stated only that he was sworn to secrecy. During the First World War, with the city on high alert, rumours of the underground escape tunnels flourished and Cameron was at the heart of the gossip. Despite all eyes being on him, Cameron didn’t say a word. It wasn’t until later—when the war was over, and Cameron was at the end of his life—that he let a few details slip. Supposedly, Cameron had been employed to build two tunnels: one from Citadel Hill to the waterfront, the other from the waterfront to George’s Island. They were indeed escape tunnels, and not the sewer system others claimed them to be. Additional support for this theory comes from testing done in the 1970s when many of the tunnels downtown reopened. Samples were taken from the wood floors to check for signs of human excrement, but no evidence was found. If these passages were used as a sewer, where’s the sewage?

It is possible that the tunnels under Halifax’s streets were used by the military as a sort mail fast mail route. In a Chronicle Herald interview in the 1970s, archaeologist Richard Fairweather stated: “The only subterranean passages shown on old plans are drains. The military would never have indicated secret routes on public plans. Every fortress had to have some way of getting couriers out… the planking is a dead giveaway…”

There are also several personal accounts from citizens who claim to have taken passageways from the Citadel to the waterfront, some claiming they travelled as far as George’s Island. Eva Goodall Hill, from Hantsport, Nova Scotia, wrote a letter to the Chronicle Herald in 1978, describing a journey she and her father took through a tunnel in the Citadel:

In 1907 my father took me down the passageway from Citadel Hill to Georges Island. My father used to speak of this passageway as it was usually used by the troops going on guard duty to Georges Island. I recall we went down several steps (made of granite blocks) which were inside the fort. My father was 6’2” tall and he had to bend his head a little all the way down the passage… I remember the ceiling, floor and walls were made of red shiny brick… We walked for several minutes when we came to a place where there were beads of water on the ceiling because we were under the strip of water between the shore and the Island. After showing me the cannon and the guardhouse on the island my father asked the guard to hail a boat to take us to shore… This episode in my life is as vivid as the Halifax Explosion… (Feb. 17, 1978).

The problem with these accounts is that there is more evidence against them than for them. They make for great storytelling, but they don’t provide substantial proof. John William Cameron may have been under a military contract that discussed the possibilities of a tunnel to George’s Island, but the evidence says no tunnel was ever built. If the passages we know of were for military couriers, where is the entrance to the Fort? Mrs. Goodhall Hill’s account is a compelling one, but she describes a tunnel made entirely of red brick; the photographic evidence we have of the passages that are large enough for a person to walk in comfortably appear to be made of ironstone with a wood floor.

Does that mean these stories are nothing but lies? Not at all. What it means is that in order to validate these accounts, we need more information. Perhaps somewhere, buried deep in an archive, library, or military classified file, there is something that will make these pieces fit in with the information we already have.

Tunnels in the modern era

The real truth is that whether they were for sewers or other services, the British did bring their love of tunnels to Halifax. People continued to remain curious about the tunnels that have been found, as well as fantasized about the tunnels that could exist. The idea of a passageway between the shore and George’s Island remains particularly prominent.

As technology advanced, the idea of building a modern underwater tunnel didn’t seem so far-fetched, or dangerous. In fact, it was seriously considered. In the 1960s, the Halifax-Dartmouth Bridge Commission was in the middle of a great debate. There was no doubt that traffic was increasing and that a new way for vehicles to cross the harbour was needed. They could go the traditional route with another bridge, or they could try something more daring.

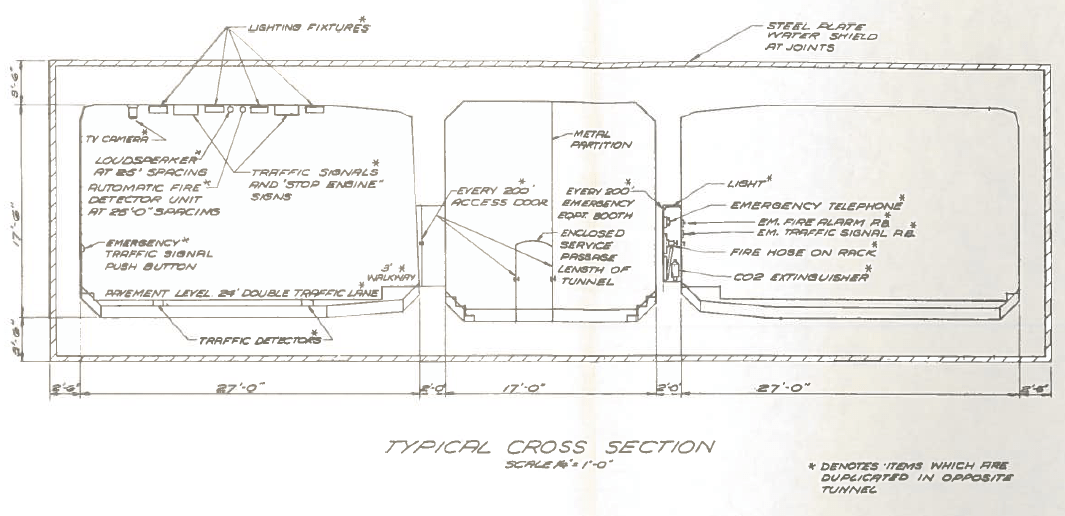

The Commission had a study conducted by Canadian Bechtel Ltd. regarding the feasibility of a tunnel from downtown Halifax to Woodside in Dartmouth that would pass near George’s Island. The passage would be made of prefabricated tubes, rather than fully dug under the ground, a technique which was seen to have many benefits:

Unlike a bored tunnel, which must go far enough below the harbour bottom to get into good rock, the pre-cast sections may be laid directly on the bottom with a minimum of preparation. … Unlike a drilled tunnel, which depends on the soundness, or otherwise, of the rock above it, a fabricated tunnel can be built to known strength and therefore has much greater resistance to both imposed and natural forces such as earthquakes. In addition, many phases of the work can be done at the same time (Halifax-Dartmouth Bridge Commission Study for Halifax-Dartmouth Vehicular Tunnel George Island Location, Canadian Bechtel Ltd, Page 4).

In the proposal, which was a part of the greater Harbour Drive/Cogswell Interchange project, it was suggested that access to the tube from the Halifax side would begin at the corner of Salter and Lower Water Streets, and near Pleasant Street on the Dartmouth side. The underwater length of the passage would be approximately 5200 feet, or around 1.6 kilometres. The idea behind having the tunnel pass so close to George’s Island was not to offer it as a possible destination for motorists, but rather to act as a station for additional ventilation.

It was estimated that the project would take upwards of 35 months, or almost three years to complete, at a total cost of 37.5 million dollars. Ultimately, as we know, the choice was made to go with the more traditional bridge option, which gave us the A. Murray MacKay Bridge we know today.

The reality of an underwater tunnel remains just a pipe dream.

Looking forward

“Persistent Fairy Tales” —that is how The Mail-Star referred to the legend of the Halifax tunnels in 1973, but even they admit these folktales have value: “Despite historians, however, the engaging fairy tales will persist. It is just as well; they serve admirable to embellish the colourful story of Fortress Halifax, The Warden of the Honour of the North.”

These stories have the merit of the heart that keeps us young. They give our imagination a place to get some well-deserved exercise, and who knows? Maybe the future will bring with it some new discovery that confirms everything we’ve dreamed to be true.

Special Thanks to Elena and the Halifax Municipal Archives, opens a new window.

Tunnel timeline

Library resources

“Ghost Islands of Nova Scotia” by Mike Parker, Ref 971.6 P242gf, opens a new window

Chronicle Herald:

“Underground Halifax holds tourist potential” by Barbara Hinds, Sept 14 1976

“Tunnels spur interest” by Dianne Marshall, August 21, 2005 page 3

“Voice of the people: Passage way” letter from Eva Goodall Hill, February 17, 1978

The Mail-Star:

“Persistent fairy tales”, October 30, 1973

“Tunnel to George’s Island”, August 11, 1978

Halifax Public Libraries Postcard Collection:

Community resources

Halifax Municipal Archives:, opens a new window

102-39B.1427.S-13 - George Street Tunnel, 1973

102-16N-0068.24 – Construction of Scotia Square, 1968

CR30K-1-17.22 – The Halifax Club, Pam Collins

624.193_H_1964 – Halifax Dartmouth Bridge Commission Study, Diagrams SK-C-3 and SK-C-2, Canadian Bechtel Ltd.

Halifax/Dartmouth City Minutes - https://www.halifax.ca/about-halifax/municipal-archives/source-guides/historical-council-minutes

Online resources

BBC:

“The lost tunnels buried deep beneath the UK”, opens a new window

Canadian Encyclopedia:

Halifax Citadel, opens a new window

CBC:

“Possible discovery of mystery tunnel just a pipe dream”, opens a new window

“Underground Halifax”, opens a new window

City News:

CTV News:

“What lies beneath: Uncovering the mystery of the Halifax tunnels”, opens a new window

Facebook, Halifax Then & Now, opens a new window

Hampshire Live:

“The hidden tunnels below Portsmouth that became a top level Cold War target”, opens a new window

Halifax Examiner:

Halifax Military Heritage Preservation Society:

“George’s Island/Fort Charlotte”, opens a new window

Look and Learn:

New York Post:

“Mysterious Florida tunnels’ secrets revealed”: https://nypost.com/2018/12/05/mysterious-florida-tunnels-secrets-revealed/

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Centre:

Nova Scotia Archives:

https://archives.novascotia.ca/easson/exhibit/archives/?ID=14

https://archives.novascotia.ca/macaskill/archives/?ID=4056

https://archives.novascotia.ca/photocollection/archives/?ID=260

https://archives.novascotia.ca/eastcoastport/archives/?ID=86

https://archives.novascotia.ca/photocollection/archives/?ID=9159

https://archives.novascotia.ca/macaskill/archives/?ID=1388

https://archives.novascotia.ca/dennis/archives/?ID=32

Parks Canada History:

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History, opens a new window

Smithsonian Magazine:

“The Epic Struggle to Tunnel Under the Thames”, opens a new window

Tampa Bay Times:

Wikipedia Commons:

Fort Southwick WW2 Tunnels 6, opens a new window

The Banqueting Hall, opens a new window

Bedford Institute of Oceanography May 2019, opens a new window

Youtube:

The Halifax Commoner, “Frozen in Time: Halifax’s Secret Tunnels”, opens a new window

Add a comment to: The Tunnels of Halifax – Fact and Fiction: A Brief and Not at All Definitive History