Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library,, opens a new window in collaboration with Halifax Public Libraries' Local History Team

We all know that adage— "the squeaky wheel gets the grease"—if you want something to change you’d better speak up, you’d better be loud, and you’d better be persistent.

Because change rarely comes quietly.

James (Jim) Bigney was born in St. John, New Brunswick, and moved to Halifax in 1979. He worked for the Department of National Defense as a base supply worker at the HMC Dockyard. His partner, John Morrow, was from Halifax. In his youth, John was active with the YMCA and the Special Olympics. Though he lived in Ottawa for a time, he returned to Halifax to pursue an education in food service at the Dartmouth Vocational School. With these skills, he worked at Les Deux Amis Restaurant, the Five Fishermen, and the Evangeline Room in the Westin Nova Scotian.

Jim and John were a couple for more than 10 years. When John died in 1993, Jim applied for the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) survivor benefit, but the claim was denied. Jim knew that it would be because his same-sex relationship was not recognized by the Canadian government. Jim knew that this was not right, not just for him but for all people in same-sex relationships, and so he decided to take a stand. Let’s take a look at Jim Bigney’s fight for equality, and how he helped change the path of 2SLGBTQIA+ rights in Canada.

Jim and John

“You can call the police, you can do whatever. No one is going in that room… Nobody is going in that room until someone tells me what is wrong with him.”

— Jim Bigney, AAHP Interview, August 6, 2015.

Jim knew something was wrong.

John was not well. He had a persistent cough, an abscessed tooth, and he had gotten thin. John was withdrawn, and wouldn’t discuss what was going on. Jim confronted him and forced him to go to the hospital, yet it took two visits before John was admitted. Despite being John’s partner, Jim was largely kept in the dark about his condition: “… because they weren’t regarding me as the next of kin they weren’t telling me anything. Right? Which, I found very frustrating” (Bigney, AAHP interview 2015). After John was confined to a hospital bed for two to three weeks, Jim stood outside the door and blocked the medical staff from entering his room: “You can call the police, you can do whatever. No one is going in that room… Nobody is going in that room until someone tells me what is wrong with him” (Bigney, AAHP Interview 2015). The doctor informed him that John had been diagnosed with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and that he wasn’t expected to live more than a month. When Jim went back into John’s room, he gave him a hug and a kiss and told him: “John, I love you as much today as I did thirteen years ago, and for whatever reason life has given us this walk and you’ve got to know that I will be there, honey, going everywhere. Just so you know. Just so you know” (Bigney, AAHP interview 2015).

For the next six months, Jim was John’s primary caregiver. When he was home, Jim made sure John got his medication and he bathed him; when he was at work he arranged for home services through the AIDS Coalition of Nova Scotia. The home service support was a necessity because Jim’s employer, the Department of National Defense, would not grant Jim family leave, even after he had used all his vacation days looking after John: “…when I wanted to take a family-related day off to go visit him or if his health was sustained high enough that I could take him out on a day excursion somewhere… they wouldn’t recognize it, because I had put down my same gender… I would take it to my union four or five times“ (Bigney, AAHP Interview 2015).

During this time, John was in and out of the hospital. He was having difficulty remembering things, and his ability to make decisions was called into question. His family considered putting him in an institution, and because he was not recognized as John’s spouse, Jim would not have been able to stop them. Jim knew that to have any say in John’s care and treatment, he needed to have John’s power of attorney (POA). And so he arranged the paperwork. The day the lawyers came to the Victoria General Hospital to see John, Jim had talked with him about what he would need to remember to prove he was competent enough to make the decision to put him in charge. John passed the doctor’s questions, and he and the lawyers signed the POA and a will.

Although John’s condition had ups and downs, it was ultimately a losing battle. He had developed brain cancer, and his immune system was too compromised to treat the tumour.

On the morning of November 29, 1993, Jim left for work leaving John with a caregiver. Not long after arriving at the dockyard, he received a call to tell him John had been taken to the hospital. Jim told his supervisor he was not feeling well and needed to leave: “And instead of going to the hospital I went down to the park and I sat, I don’t know, three, four hours underneath a tree. I cried. I screamed. I talked to the tree… And, then finally, I got myself okay.” When he arrived at the hospital around 2pm, he knew John’s fight was almost over. Jim lay in the hospital bed beside John; he talked to him and sang to him. And just before midnight, John died peacefully in Jim’s arms.

John’s funeral was held on December 3, 1993, at All Saints Cathedral and was buried at Camp Hill Cemetery. Jim paid for John’s funeral, but he wasn’t entitled to bereavement leave: “…when John passed away I put in for bereavement leave, and it was denied. I had to use sick leave instead” (Bigney, The Daily News, March 14, 1994 pg 4). Just before Christmas, Jim applied for the survivor benefit through the Canadian Pension Plan. The benefit would have been between $300-$350 per month. In early 1994, he received a letter back stating that the claim was denied: “… I sent it back to them. I don’t accept this, type of thing…” (Bigney, AAHP Interview 2015). Nothing about the past several months had been fair or easy, and the rejection of the CPP survivor benefit was the last straw. It wasn’t a matter of money; it was a matter of principle.

Fighting for what's right

“I’ve thought about it and I’ve thought about it. And I’ve tried to be objective and unemotional about it and it comes down to homophobia.”

— Jim Bigney, The Daily News, March 14, 1994, page 4.

For the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, fighting for basic human rights is a familiar occurrence. The first Canadian law specifically against homosexuality was brought into effect in 1841. When first enacted homosexuality was punishable by death; later it was changed to time in jail. In 1969, Federal Minister of Justice Pierre Elliott Trudeau presented a bill which decriminalized homosexuality between consenting adults over the age of 21. It was a move that perhaps made some members of the community feel safer about being their authentic selves, but it did not retract or resolve other discriminatory practices. The first large-scale gay rights gathering in Canada took place in August of 1971 on Parliament Hill, Ottawa. That same day, another protest took place at Robson Square in Vancouver. By 1973, the first Pride celebrations were being held in Canadian cities like Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Saskatoon, Vancouver, and Winnipeg. On the local scene, the Halifax community had their first public demonstration in 1977, with a rally against the CBC. They were protesting the CBC’s refusal to run a piece about the Gay Alliance for Equality’s Gayline. The Gayline was a service that offered specific resources and support to 2SLGBTQIA+ people in the city. Halifax’s first Pride March was held later in 1988.

But despite protests, advocacy groups, petitions, and educational conferences, a hatred for 2SLGBTQIA+ people remained ingrained in society, and in government. Jim knew that was the reason he was denied both his family and bereavement leave, and the reason he was denied the CPP survivor benefit: “I’ve thought about it and I’ve thought about it. And I’ve tried to be objective and unemotional about it and it comes down to homophobia” (Bigney, The Daily News, March 14, 1994 p 4). Jim did not want anyone else in his situation to experience this same blatant discrimination. And so, he took his complaint to the Human Rights Commission of Canada (HRCC).

The HRCC ordered a tribunal to be held regarding Jim’s case, which would allow them to investigate his claim. However, the Attorney General argued for a stay based on s.62 of the Human Rights Act, which states that investigations cannot be made into pre-1978 pension plans. In turn, the HRCC claimed that s.62 was unconstitutional, and they should be allowed to look at Jim’s case on that basis. The tribunal was continuously delayed until it was ultimately decided by the Supreme Court of Canada that the HRCC “… did not possess the expertise, and therefore jurisdiction, to determine the constitutionality of its own enabling legislation” (Wayves, April 2, 1999 p 2). The HRCC was never able to hear Jim’s case.

Asking for help

“I’m asking you if you could do it pro bono…”

— Jim Bigney, AAHP Interview, August 6, 2015.

This ongoing process took four years.

During this time, Jim was suffering: “...I was not only grieving. I think I was in post-traumatic stress. Because, for two years I turned to alcohol, drugs… I signed myself into a facility outside the city for help. I wasn’t an alcoholic. I wasn’t a drug addict, but I needed help to sort through this whole thing” (AAHP Interview, 2015). After completing the program at the facility, Jim returned ready to fight even harder. He helped the gay community and the AIDS community through fundraising, raising awareness, and letter-writing campaigns: “The Mayor, the premier… I didn’t care if you had a phone number, you had an office, I knocked on your door” (AAHP Interview, 2015). He got to know other people fighting their own human rights fights, like Wilson Hodder. Wilson filed a discrimination case with the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission after his partner passed away, and his claim for survivor benefits from the Nova Scotia Department of Education was also rejected.

While he waited for the outcome through the HRCC, Jim did have a small victory. Jim’s employer, the Department of National Defense, returned his family and bereavement time to him… 14 months late. However, they made it clear this was not a change of policy: “The Treasury Board said it acted on humanitarian grounds and the decision is ‘without prejudice’ – ‘legal jargon’ for no precedent…” (Rossiter, The Daily News, February 20, 1985, page 5). This meant that in the future the Department of National Defense would not have to offer the same compensation to other 2SLGBTQIA+ employees. In a Chronicle Herald article, Jim stated: “Certainly there has been a victory, ever so small, in the right direction toward recognizing same-gender partners… And that I’m happy about. But again, I think they make it excruciatingly painful… to get what should be a right – equal rights and treatment.” (Conrad, Chronicle Herald, February 20, 1985, page unknown).

For Jim, the end of the case with the HRCC was just the beginning. Because he was challenging the federal pension program, he was going to take on the federal government itself. He went to local lawyer Anne Derrick—who was known for taking human rights cases—and presented his story: “…I went into her office and I explained what I wanted for her. I said, ‘I’m asking you if you could do it pro bono…’” (AAHP Interview 2015). After a few days of consideration, she accepted the challenge.

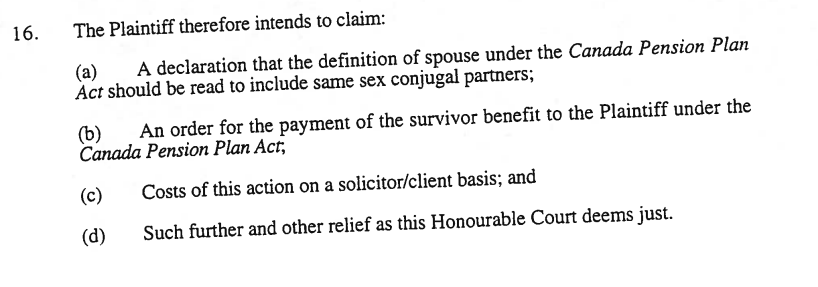

The lawsuit against CPP asked for both payments of the survivor benefit, and for legal fees for the case. A 1999 Wayves article by Michael Wile stated: “Bigney’s suit is not the first involving the federal pension program, but it is believed to be the first involving a surviving partner in a same-sex relationship” (Wayves, May 1999, page 1). But there was more. They were also seeking for the definition of the word “spouse” to be changed in CPP legislation. At that time, “spouse” was defined as a partner of the opposite sex who had been living with the person paying into CPP for at least a year. Same-sex/same-gendered couples were not included. The case against the government was filed in April of 1999 with support from the advocacy group Equality for Gays and Lesbians Everywhere (EGALE).

Time for change

“You didn’t get that right. It makes it sound like I quit, and I wasn’t gonna quit.”

— Jim Bigney, AAHP Interview, 2015.

Throughout the 1990s, the 2SLGBTQIA+ community achieved victories through court cases and governmental change, although the change was slow. In 1992, it was determined that the Canada Human Rights Act was discriminatory for not including protections for sexual orientation. It took three years to implement official changes to the Act itself. Also in 1992, the federal court lifted Canada’s ban on homosexuals in the military.

In 1995, a court case in Ontario ruled that same-sex couples were allowed to adopt children; British Columbia, Alberta, and Nova Scotia followed shortly afterward. In another 1995 case, a Manitoba court found that denial of spousal benefits under an employment benefit plan based on sexual orientation was discriminatory under the province’s Human Rights Code.

In April of 1998, the Ontario Board of Appeal determined that the term “spouse” as it is defined in the Income Tax Act was unconstitutional. This change to the Income Tax Act had a trickle-down effect on the Nova Scotia Public Service Superannuation Act, the Teachers Pension Act, and ultimately the province as a whole. That year, Nova Scotia became the first province to acknowledge homosexual couples as equal to heterosexual couples. For people like Wilson Hodder, this meant that he was now recognized as a legitimate spouse and was entitled to the spousal benefits left behind by his partner. At the time of the decision, Hodder was granted over $37,000 in back payments (Armstrong, Chronicle Herald, May 26, 1998, pg A1-A2).

In May of 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada made a ruling regarding two women who had been in a relationship for more than a decade. When the couple broke up, one partner sued the other for spousal support under the Ontario Family Law Act, and it was determined that the definition of spouse, which referred strictly to a man and a woman violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Ontario was given a deadline to change the wording of the Act.

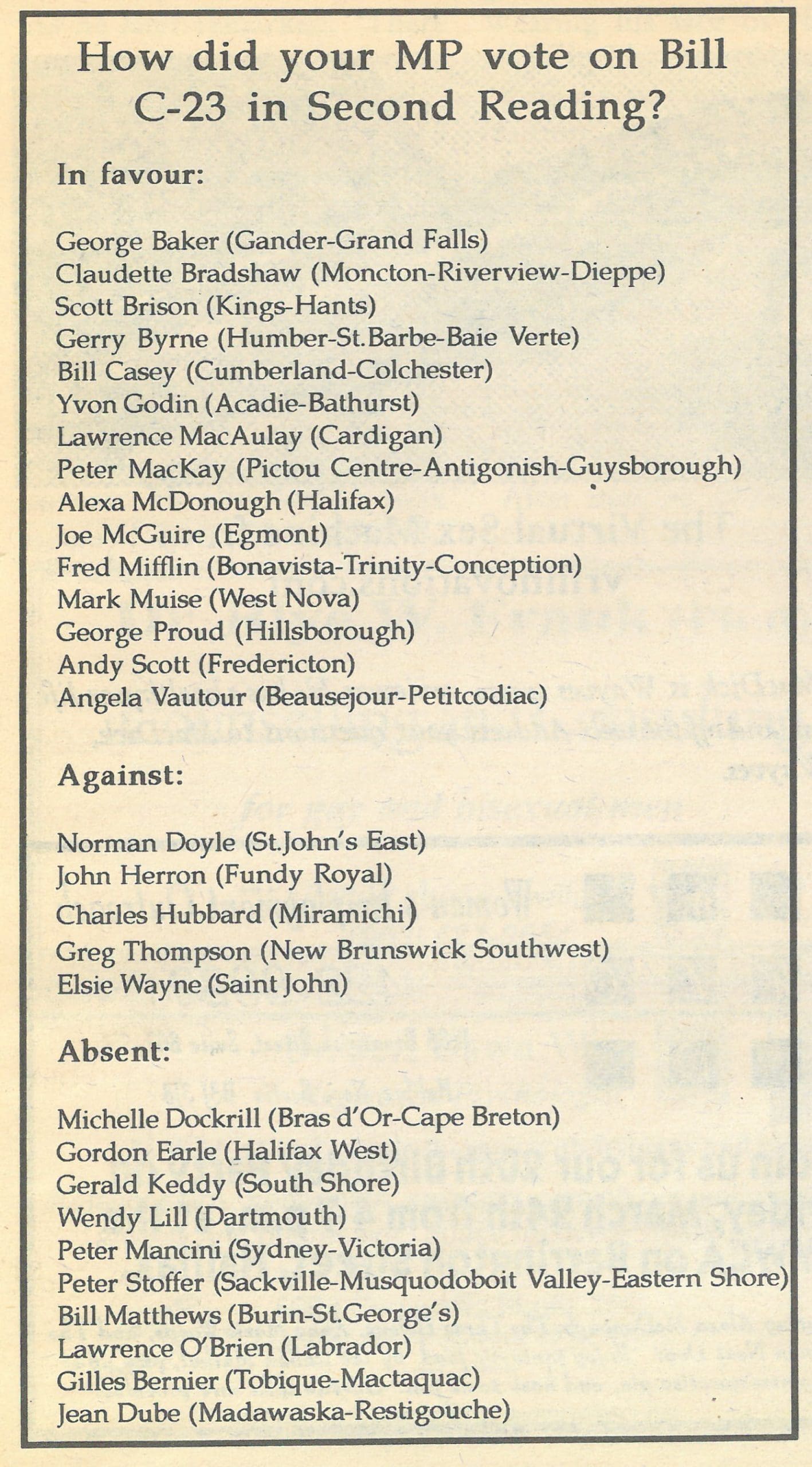

Jim’s case against the CPP, in conjunction with the rulings in these and other cases, put extreme pressure on the Liberal Government: “… if the government didn’t push through… we would go to the supreme court and we were so confident that we would win, and the government knew that” (Bigney, AAHP Interview, 2015). In February of 2000, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien introduced Bill C-23. This Omnibus Bill was intended to make changes to the Benefits and Obligations Act and several other pieces of federal legislation to give same-sex couples who have lived together for more than a year the same benefits as common-law couples: “This Bill amends all federal legislation dealing with relationships, including those dealing with children” (Vance, Wayves, March 2000, p 8). By June of 2000, after three readings in the House of Commons, Bill C-23 had been given Royal Assent by the Governor-General. It was going to be made law.

With the amendments being made to the Benefits and Obligations Act, Jim and his lawyer Anne were now in a bit of a limbo. The policy was changing, but Jim had not yet received what he was owed. The case was placed into abeyance—a temporary suspension—as they waited for word. On February 16, 2001, an article appeared in the Chronicle Herald: “Gay man drops suit against Ottawa; Five-year fight focused on survivor pension." When Jim saw the headline, he was taken aback. He hadn’t dropped the case at all. He contacted the reporter and told them: “You didn’t get that right. It makes it sound like I quit, and I wasn’t gonna quit” (AAHP Interview, 2015).

A hard-fought win

“I’d do it again a thousand times over.”

— Jim Bigney, Chronicle Herald article, 2001

Before the end of February 2001, Jim received word of his settlement, the details of which were not publically disclosed. Of the settlement, Michael Donovan, head of the civil litigation for the Justice Department’s Atlantic region stated: “… the settlement was intended to put him (Mr. Bigney) in the same position he would have been in if he’d been in a common-law relationship” (Borden, Chronicle Herald, February 28, 2001 p A6). On February 28, the same Chronicle Herald reporter who had run the piece about Jim dropping his suit did a follow-up article: “Price in the face of prejudice; Grief of losing partner to AIDS mingles with joy of victory in CPP benefits case.” In the article, Anne Derrick underscored what Jim had said from the beginning of his fight: it was never about the money: “For him (Jim) this was a very long struggle… It wasn’t about the money, it was about being accorded his equality rights and ensuring that other gays and lesbians are also accorded those rights.” Despite all of the hardships, the discrimination, the time, and the emotional burden Jim carried with him, Jim knew how important it was to secure this victory: “[This] may not eradicate homophobia… may not do too much for some people in certain areas who think that being gay is abhorrent – but what it does is makes us legitimate people… I’d do it again a thousand times over.”

The finishing lines

Jim’s legal battle, and the battles of other 2SLGBTQIA+ people across the country paved the way for the future. By September 2004, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court ruled that banning same-sex marriage was unconstitutional, and the definition of marriage was changed from a union between a man and a woman to “the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others.” In July 2005, Bill C-38 was passed at the Federal level of government, giving same-sex couples the right to marry. The definition of “spouse” had been rewritten. Even though these battles have been won, that doesn’t mean the war is over. Jim’s fight for equality was only concluded within the past 20 years. It is the definition of recent history.

As we celebrate Pride in Halifax, it is important to remember that it is not all rainbows and parades. It is vitally important that as a society we continue to educate ourselves, to see the world from new perspectives, and recognize that 2SLGBTQIA+ rights are human rights.

Library resources

“Before the Parade” by Rebecca Rose, 2019 306.7609716 R797b, opens a new window

Eureka

Cape Breton Post: Man suing feds for same-sex benefits by Kevin Carmichael, April 8, 1999, p 8

The Chronicle Herald: Gay man drops suit against Ottawa; Five-year fight focused on survivor penion by Sherri Borden, February 16, 2001, p A3

The Chronicle Herald: Pride in the face of prejudice; Grief of losing partner to AIDS mingles with joy of victory in CPP benefits case by Sherri Borden, February 28, 2001, p A6

The Daily News: Newsmaker Q & A: JIM BIGNEY ‘It’s got to be homophobia,’ says man seeking benefits after long-time partner died by Tom Regan, March 14, 1994, p 4

The Daily News: B.C. same-sex benefits win could help Halifax activist by Michael Lightstone, March 30, 1994, p 7

The Daily News: Gay man sues for pension by Rachel Boomer, March 30, 1999

The Daily News: Feds defend spousal terms by Rachel Boomer, May 15, 1999, p 5

Hamilton Spectator: Pension fight began in ’93 Nova Scotia man still pursuing same-sex battle, April 8, 1999, p D5

Microfilm

The Chronicle Herald: Pride in the face of prejudice; Grief of losing partner to AIDS mingles with joy of victory in CPP benefits case by Sherri Borden, February 28, 2001, p A6

Vertical File

Halifax Chronicle Herald: Feds relent a big on gay rights by Rick Conrad, February 20, 1995, page unknown

Halifax Chronicle Herald: Pride amid prejudice: gays frustrated by decision by Rick Conrad, July 8, 1995, page unknown

Halifax Chronicle Herald: Gay widowers file human rights complains by Rick Conrad, July 26, 1995, p A4

Halifax Chronicle Herald: Same Sex Benefits Approved by Frank Armstrong, May 26, 1998, p A2

The Daily News

Feds give in to gay worker, but refuse to set precedent by Jim Rossiter, February 20, 1995, p 5

Wayves

Halifax Activist Receives Court Challenges Funding, April 1999, p 2

Jim Bigney’s Pension Pursuit by Michael Wile, May 1999, p 1

Court Ruling and Ottawa vote to change pension landscape, June 1999, p 1

It’s about time… Bill C-23 hits the House of Commons by Kim Vance, March, 2000, p 8

Domestic Bliss? Nova Scotia introduces registered domestic partnership legislation by Kim Vance, Dec/Jan 2000-2001, p 1

Online resources

AIDS Activist Project, opens a new window

James Bigney Interview, 2015 , opens a new window

James Bigney V The Queen (Court Proceedings), opens a new window

CBC, TIMLINE: Same-sex rights in Canada, 2012, opens a new window

Everybody Wiki, James Bigney, opens a new window

Findlay, Barbara, Q. C., Queer Cases: A Selected Chronology, opens a new window

Halifax Pride, opens a new window

Metcalfe, Robin, The Coast, Gays of Future Past, opens a new window

Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

Queer Events, Queer History: History of Canadian Pride, opens a new window

Add a comment to: The Definition of Spouse – How James Bigney Helped Change Canadian Law for Same-Sex Couples: A Brief and Not At All Definitive History