New Street on the Block

Once upon a time, long, long ago in the 1960s, construction began on Halifax's Cogswell Interchange.

The Cogswell Exchange was the initial step in a much larger urban planning project that included Harbour Drive—a six-lane highway that would have stretched from the Fairview Overpass across the entire waterfront all the way to Point Pleasant Park. To make way for this grand design, buildings were torn down, streets were removed, and overlapping highways were woven together in a tapestry of utilitarian engineering.

However, the Harbour Drive project was ultimately (and thankfully) scrapped, and, in the words of Elena Cremonese of the Halifax Municipal Archives, the Cogswell Interchange became the "Road to Nowhere."

Now, more than fifty years after it was built, the Cogswell Interchange is being dismantled. The sterile crisscrosses of concrete are to be replaced with roundabouts, pocket parks, greater pedestrian access, and three new streets, including one named after Dr. Alfred Waddell.

But who is Dr. Alfred Waddell, besides being the new kid on the block?

Leaving the Island

Alfred Ernest Waddell was born in Tunapuna, Trinidad, on August 25, 1896. His father, Joseph Waddell (1853-1907), is believed to have been born in Trinidad and is likely of Scottish descent. He worked for thirty-seven years as the Head Master of the Tunapuna Government School before being forced to retire due to illness. His mother, Claudine (nee Abbott) (1866-1929), was born in Petit Saint Vincent, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and worked as the Tunapuna Registrar. Alfred was the middle child of the family, having three younger siblings and three older siblings.

Unfortunately for Alfred, his father, Joseph, passed away in 1907 when Alfred was just eleven years old.

There is not a lot of public information known about Alfred's childhood in Trinidad. We know that he could fluently speak both English and Spanish and that in his twenties, he worked as a civil servant in Tunapuna. We also know that he was in a relationship with Emelia M. Castillo from Caura, Saint George, Trinidad. In 1923, the couple travelled to Bermuda, and on October 19, they boarded the ship Chaleur and set sail for New York. During their marriage, the Waddells were blessed with four children: Winifred (Winnie), Alfred (Fred), Joseph (Joey or Joe), and Sylvia.

Alfred and Emilia had come to New York with one goal in mind: for Alfred to become a doctor. "In those days when a family member was sent abroad to study, the understanding was that that family member would achieve some rate of success with studies and then would come back home and then subsidize the next family member in turn," says Alfred and Emilia's daughter Winnifred in a documentary about Alfred called Scattering of Seeds: Episode #9 -Before His Time, Dr. Alfred E. Waddell. And so Alfred began his pre-med degree at Columbia University while working night shifts as an elevator operator and later a factory worker. Emilia not only took care of their growing family but also worked in a textile sweatshop to supplement the family income.

Dalhousie Medical School

Alfred knew that becoming a doctor would be no easy feat. Not only was the education expensive and challenging, but he was living in 1920s America and he was mixed race.

Although African Americans had won freedom from enslavement through the American Civil War (1861-1865), Jim Crow Laws in the American Southern States effectively made racism legal and made Black people the targets of race-related violence, segregation, and discrimination. As a result, upwards of 750,000 African Americans migrated to the Northern United States by the 1920s in hopes of finding better opportunities and better treatment. However, when confronted by new competition in the job and housing markets, discrimination towards African Americans in the Northern States began to rise. There were unofficial racist practices regarding housing, education, justice, and city development in place.

Despite the challenges he faced, Alfred completed his pre-med studies. He then needed to decide where to get his Degree in Medicine. An American degree would not be recognized at home in Trinidad, but a British one would be. In 1928, he made the difficult decision to leave his family and travel to Halifax to attend Dalhousie University's medical program. Alfred's arrival in Halifax was not particularly welcoming. "At that time in Halifax, racial discrimination was rampant. Most students who came from the Caribbean or other countries who had dark skin were not welcome," says Dr. Ernest Marshall, a friend of the Waddell family. "Apparently, he [Alfred] couldn't find a place to stay, and he came and asked my mother if she could accommodate him, which she did" (A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9). However, his fellow students were avid supporters of Alfred. "My grandfather was the only coloured member of his class. He was a very good student, and he was very well-liked." says Ron Milne, Alfred's grandson. (A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9)

In 1932, after completing his coursework, Alfred was ready to participate in his hospital internship. However, many hospital administrators had no intention of taking Alfred on as a medical student; they believed that patients would not want a Black doctor. Alfred was worried that he would not be offered a place and would, therefore, not be able to graduate. His fellow students would not accept this; they told the administration at Dalhousie University that if Alfred was not offered an internship, they would boycott their own internships in protest. Instructors Dr. Alan Curry and Dr. H. W. Schwartz arranged for Alfred to complete his degree by interning at the Nova Scotia Sanitarium in Kentville. He finished his degree and graduated as one of Dalhousie's first Black doctors in 1933.

Alfred had originally intended to return to Trinidad when his degree was complete. However, during his time in Halifax, he had occasionally borrowed money from friends to make ends meet. He did not want to leave the city without repaying those debts, and so he decided to stay. Following his graduation, Alfred, Emilia, and their children all moved to Halifax permanently. Back in New York, Emilia had been saving all the money should could for the trip:

So come May, when we got off that boat [in Halifax], we were dressed in brand new clothes from head to foot. And when we got into the immigration shed, and they began to look at us, I believe it was the nurse in the immigration shed who made the comment "My Gracious they’re so clean", and my mother took offence at that. And my father then became very very angry, and then she said be quiet, tone down, because we want to get through here.

Winnifred, A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9

Despite the comments from the immigration staff, the Waddells had officially arrived in Canada. Alfred had found them a home on the north side of Cornwallis Street (now Nora Bernard Street), very near the Gottingen Street intersection.

Life in Halifax

Life in Halifax was a struggle, at least at first.

Alfred initially began his medical practice out of the family home at 60 Cornwallis Street. Racism in the community kept many patients away. As well, the local Black community had reservations about being treated by a doctor they did not see as fully Black.

Despite their hesitations, Alfred went above and beyond for his patients; he was a full-service doctor to the Black communities in and around Halifax. He frequently made house calls to places like Africville, Beechville, and the Prestons. These journeys were made all the more difficult in the early years as he did not own a vehicle. Sometimes, patients with cars lent them to Alfred so he could make long-distance trips out of town. Many of his underprivileged customers also could not afford to pay Alfred in the traditional sense. In lieu of money, he would frequently accept chickens or eggs in exchange for his services.

Alfred's patients included another marginalized group - the local Chinese population.

Chinese immigrants had been settling in the Maritimes since the mid-1800s. Although some had initially come to Canada's West Coast to participate in the gold rush, others made their way east and settled in Halifax to open new businesses like laundromats and restaurants. This community also felt the painful sting of racism in Nova Scotia. In February 1919, Halifax's Chinese community was the target of a race riot. Several Chinese-owned businesses were vandalized and robbed by a vicious crowd that gathered more and more people as it made its way through downtown. It took a combined force of the local police and the military and naval police to restore order.

During Alfred's formative years in the city, he frequently visited the Imperial Café, a Chinese-run business on Upper Water Street, and he came to know the owner, Ho Ling. When Ho Ling's son became incredibly sick and was expected to die, Alfred treated the boy and saved his life. From that day forward, the Chinese community came to him as a trusted source of medical advice. “I don’t think they thought about what colour he was, as long as he was a good doctor and treated them well,” said Mary Ling Mohammed, Ho Ling’s Daughter (A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9).

In 1938, Alfred further demonstrated his dedication to underprivileged communities. A smallpox outbreak was running wild through Halifax, and certain communities were quarantined in order to control the infection. At great personal risk, Alfred visited these areas armed with inoculations to vaccinate as many people as possible.

In 1939, as Alfred's practice grew and he found success, the family moved from their Cornwallis Street home. Initially, the office was located at 451 Brunswick Street (near the North Street intersection), but by 1943 they had moved to 405 Brunswick Street (about halfway in between Gerrish and Artz Streets). The family lived in the same building as the medical office until 1945, when they moved to a house at 26 Atlantic Street (5518 Atlantic Street today).

However, the big move for the family came in 1948. While Alfred's practice remained on Barrington Street, the family moved into a new home at 325 Quinpool Road, now 6583 Quinpool Road. This house was likely constructed around 1919 and was built in the Craftsman Style. This homestead offered the family more room and acted as a tangible monument to their hard work and much-deserved success.

While the Waddells often discussed one day returning to Trinidad, that choice became more and more difficult to make. The medical practice was successful. The children were graduating from high school and university; marriage and grandchildren were in their near futures. The longer the Waddells stayed in Halifax, the deeper their roots dug. As for Alfred, while his dream of becoming a successful doctor had come true, he felt like there was still a lot of work to do.

Immigrant. Doctor. Activist.

Alfred did not identify himself as Black or white. When people asked, he would tell them he was West Indian (Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9), which perhaps better encapsulated his connection to both his African and European roots. However, the colour of his skin gave him the lived experience of a Black man, which was at times difficult, brutish, and cruel. He was not the type of person who accepted this treatment quietly, and he began to speak out, becoming an activist in the community.

Not long after moving to Halifax in 1933, Alfred's sons attended a swimming class at the local pool. Upon arrival, the group of boys were split into two separate groups: one of the light-skinned children and one of the dark-skinned children. The dark-skinned children were told to come back the next day; they were not allowed to swim with the white children. Upon hearing this, Alfred "...mounted a campaign against the Mayor and the city fathers..." (Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9), demanding the pool be desegregated. Other Black parents contacted the city council, and before long, the pool was desegregated.

Alfred also petitioned the government for improvements to Africville.

Africville was a small Black community in the Bedford Basin on the outskirts of Halifax. Black immigrants had been living in the area since the 1840s, but the community was never treated as a part of the city despite being within city limits. Civic services like waste removal, water, and sewage were not offered to the residents of Africville even though they were required to pay taxes. The area was also used as a place to construct unwanted structures like an infectious disease hospital and a city dump. He advocated the government for proper sewer systems, clean water, and improvements to the roads. Unfortunately, these pleas fell on deaf ears, and none of the suggestions were ever implemented. In the 1960s, City councillors decided that Africville was going to be the site for a new port development. The citizens were forced to relocate. Their homes, their church, and their community were destroyed. Thankfully, the memory and The Spirit of Africville live on.

Another form of activism involved Alfred's role at The Clarion newspaper. The Clarion was a Black-focused newspaper founded by Carrie Best in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. what began as a church newsletter evolved to become a multi-paged publication that covered a broader geographical scope and focused on equality issues in Nova Scotia. In later years, it was renamed The Negro Citizen. Alfred began with letters to the editor that supported The Clarion and its mission:

One very important reason for the slow progress of the negro in Canada is the lack of a vehicle of expression. Press, screen and radio are practically closed avenues as far as they are concerned, so the Clarion is filling a longfelt need. At this time when inter-racial relations are in the minds and on the lips of every thinking individual, of whatever race or creed, the Clarion's appearance may be considered something in the nature of a mission. To the N. S. negroes, here is your chance to make yourselves heard. Let the Clarion be the organ for expression of your hopes, fears, aspirations, problems - your very soul.

A. E. W., The Clarion, February 15, 1947, pg. 3

Alfred later took on a more active role with the paper, acting as president of its governing body and frequently contributing articles.

In 1946, local Black business owner Viola Desmond came to Alfred's office covered in bruises. She had been arrested in New Glasgow and manhandled by the police. When visiting a movie theatre, Viola unknowingly asked for a ticket in the lower seating section, which was reserved for white people. The worker in the ticket booth instead sold her a ticket for the balcony - the Black section. Not knowing this, Viola watched the show from a seat in the lower bowl. When Viola was arrested, she was told the charge was tax evasion. The ticket Viola had attempted to purchase was slightly more expensive than the ticket in the balcony. This meant the amount of tax on the ticket was different, and she owed the government one cent. During her trial, Viola was not provided with any legal counsel or told she had the right to a lawyer. The judge in the case found her guilty and fined her $26 (or around $433 today). Despite the fact that race was not officially brought up as an issue in the case, it was quite clear that Viola's actual crime was being Black. Alfred was outraged at her treatment both by the police and by the judicial system at large, and he was not alone. The Black community was incensed, and the incident marked a rallying point for Civil Rights in Nova Scotia. Alfred worked diligently to have Viola's conviction overturned. He wrote the Attorney General on multiple occasionsto defend her and demanding she be acquitted of the crime. However, it wasn't until 2010 that Viola was granted a posthumous pardon.

All Good Things...

Alfred often came home with a headache, but one day something was different. "He came home, by taxi as I recall," Alfred's daughter Sylvia remembers, "and I went in; I went in to visit, and I spoke with him. He was in bed, and he was breathing labouriously" (A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9). On March 20, 1953, Alfred Ernest Waddell passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of fifty-six. "In those days, people were often waked at home." Sylvia explained. "The patients just came in droves. The room was filled with flowers, and people were so kind... It was just amazing, the outpouring of love at that time." (A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9) Alfred was buried in Camp Hill Cemetery. When Emilia passed away in 1998, she was buried in the same plot.

The Black community - and Halifax at large - had lost a Civil Rights champion.

The Finishing Lines

What kind of legacy has Alfred Ernest Waddell left behind?

According to his grandson Ron, it's one of compassion: "He had a sense of trying to help the underdog, the person in society who didn't have all the advantages." (A Scattering of Seeds, Episode #9). Alfred knew what it was like to struggle, to work for something better, and to stand up for what was right. Let the name Dr. Alfred Waddell and this new street act as a reminder to us all that empathy is a strength and justice is worth fighting for.

Library Resources

Heritage Houses of Nova Scotia

Noble Goals, Dedicated Doctors

Additional Sources

6583 Quinpool Road, Mia Rankin Realtor, Facebook

Africville, Canadian Museum for Human Rights

Africville, About 15 Houses..., Nova Scotia Archives

Chinese Canadians on the East Coast, Lee, Albert, Saltscapes

City of Halifax Civic Address Conversion, Halifax Regional Municipality

Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom, Library of Congress

The Clarion, Nova Scotia Archives

The Clarion, February 15, 1947, pg. 3, Nova Scotia Archives

The Clarion, August 1, 1947, pg. 1, Nova Scotia Archives

The Clarion, August 9, 1949, pg 1, Nova Scotia Archives

Cogswell interchange plan going to council vote, but some want more public consultation, Saltwire

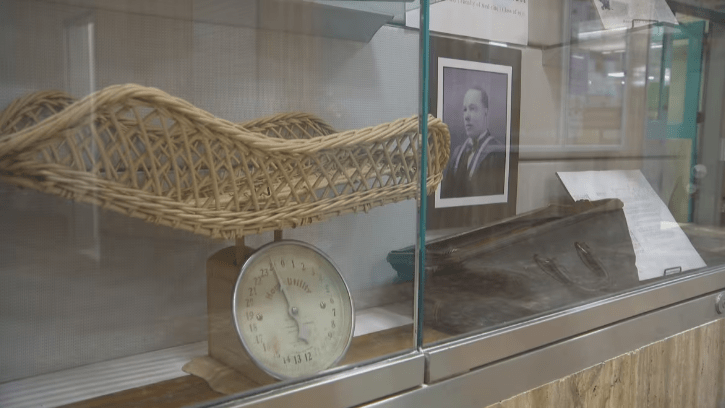

Composite Photograph of the Faculty of Medicine - Class of 1933, Dalhousie University

Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia Archives

6583 Quinpool Road, Google Maps

Halifax announces more street names for Cogswell District, CBC

Halifax honors Trinidad-born Doctor with Street Name, The Caribbean Camera

Halifax names street after Dr. Alfred E. Waddell, Surge 105

Halifax naming street after civil rights champion and 'unsung hero' Dr. Alfred Waddell, CBC

Map of the Island of Trinidad, 1912, Capt. R. E. Mallet, Internet Archive

Medicine, Dalhousie University Finding Aid

Miss Sylvia Waddell St. Patrick's Girls' School Graduation Photo, The Clarion, Nova Scotia Archives

New street names coming to the Cogswell District, Halifax Regional Municipality

Regional & Community Planning, Design Plan, Halifax Regional Municipality

Richmond vs. The Old North End, The Old North End

Should Cornwallis Street be renamed for Dr. Alfred Waddell, civil-rights pioneer?, CBC

To the Editor of the Clarion, The Clarion, Nova Scotia Archives

Trial of Viola Desmond, Britannica

Trinidad Year Book, 1923, Internet Archive

US Society in the 1920s - OCR A, BBC

Waddell, Alfred, African American Registry

Waddell, Dr. Alfred Ernest, Death Registration, Nova Scotia Archives

Add a comment to: Street Smart: Dr. Alfred Waddell Street