Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window

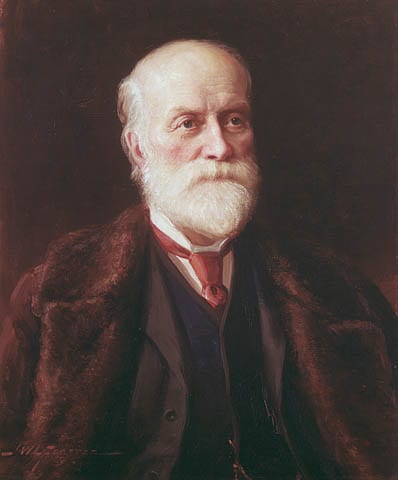

If you were a Canadian watching TV in the 1990s, you knew about Sir Sandford Fleming.

Historica Canada’s Heritage Minutes, opens a new window taught us that Sandford Fleming was not only a major player in helping to design and build Canada’s railroad system, but he also advocated for the idea of Standard Time in Canada and around the world. Standard Time—an alternative to Daylight Time where clocks were set from town to town based on the position of the sun—divided the globe into 24 time zones in an effort to help keep time consistently. This system was proposed by Fleming at the International Prime Meridian Conference in Washington, DC in 1884. Ultimately, all 25 countries who attended the event agreed to adopt Standard Time, with the rest of the world to follow suit. It is still, in essence, the system of time zones we use today.

During his lifetime, Fleming may have received recognition both nationally and internationally for his accomplishments in standardizing time zones and railways, but his primary legacy in Halifax is something you’re not likely to see reenacted on television. After Fleming gave the world the gift of time, he gave Nova Scotia the gift of space: Sir Sandford Fleming Park.

Fleming in Halifax

Sandford Arnot Fleming was born in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, on January 7, 1827, to Andrew and Elizabeth (nee. Arnot) Fleming. Fleming had a mind for engineering from an early age, and by 14 years old, he had already begun his studies under engineer and surveyor John Sang. In 1845 when he was 18, he sailed to Canada from Glasgow, Scotland, aboard the Brilliant. Ultimately, Fleming chose the province of Ontario as his first Canadian home. He began his career by selling his own hand-drawn maps of Ontario towns, including Peterborough and Newcastle. He worked while he studied, and in 1849 he travelled to Montreal and successfully passed the examinations needed for him to obtain a license as a land surveyor. With this license, he began to find employment by mapping out potential railway lines.

Fleming proved adept in the railway business. He secured a position with the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Railway in 1857. Less than 10 years later, he was approached by the government to begin surveys for a railroad that would run from Quebec City to Halifax and Saint John. Fleming’s findings would lay the groundwork for the Intercolonial Railway that would connect the Maritimes to Central Canada. He was the head engineer of the Intercolonial Railway, and would go on to become the head engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway as well.

Though Fleming’s primary residence was his house Winterholme in Ottawa, Fleming felt a deep connection to Nova Scotia. The province reminded him of his native Scotland, and so beginning around 1868 Fleming and his family spent many of their summers in Halifax.

One of Fleming’s first residences in town was a one-and-a-half-story wood home located on Brunswick Street near North Street. It is believed he lived in the home from 1868-1873, though documents indicate he continued to own the property for several years after. It is currently home to Shelter Nova Scotia, opens a new window, an organization that helps people make the transition from incarceration to community living, and supports people experiencing homelessness.

His second house, built by William Duffus, was in the south end of the city off Oxford Street. Constructed around 1871 and purchased by Fleming between 1872-1874, it was a much grander home that included multiple fireplaces, eight bedrooms, and a dining room that could host at least 14 guests. It was called Blenheim Cottage but was often referred to simply as The Lodge. It is currently a private residence.

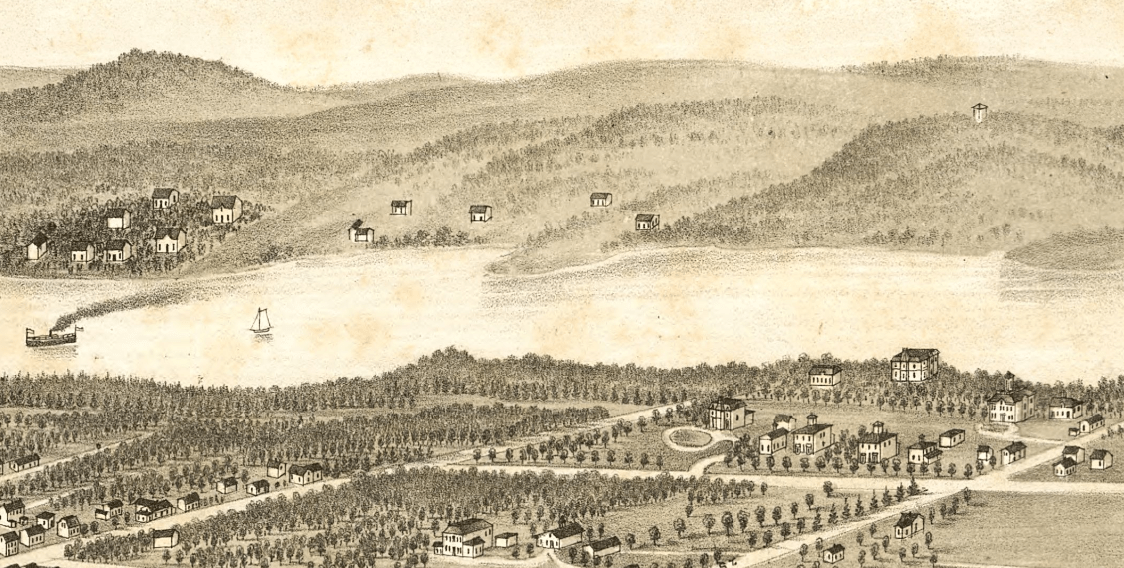

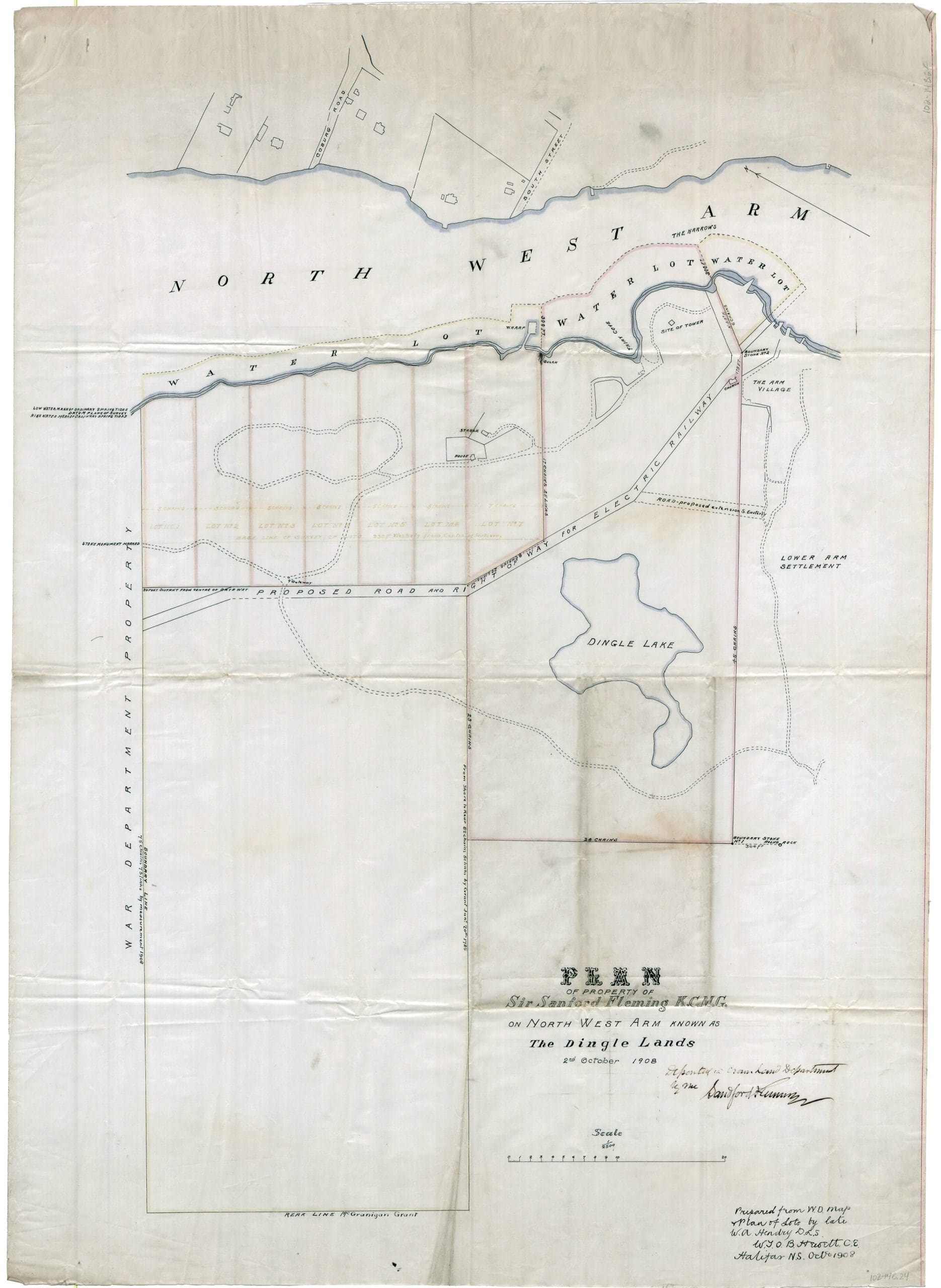

The Dingle

Sometime before the purchase of Blenheim Cottage, Fleming began to acquire land on the western side of the North West Arm, which at that time was outside of Halifax city limits. This land had been taken by the British government and divided into lots that were granted to various Halifax residents through the 1760s and 1770s. The lands had been divided and changed hands several times since it had been originally granted, but Fleming worked with new owners and inheritors until he had purchased one continuous plot of land that stretched from Melville Island Military Prison to Jollimore Village. It included over a mile of water access to the North West Arm. Around 1870, he built a small cottage on the property, which still stands today.

Fleming called the property the Dingle, a name that had been used to refer to the area before he took ownership of it. Although it is not certain exactly where the name Dingle came from, a few popular theories prevail. Fleming himself believed that the name was a reference to Dingle, a small town on Ireland’s southwestern coast. Others speculate it was named after Richard Dingle, a farmer who owned and operated a mill further down the shore nearer to the mouth of the Arm in the 1820s. It is also possible that perhaps the name simply comes from the traditional definition of the word “dingle,” which is a small, wooded valley, or dell.

Though he had the title to the estate, had built two homes (which were later destroyed), and a cottage on the property, Fleming kept the land open to the general public and allowed citizens to access both the woods and ocean. It is said that upon seeing the increasing development of social and boating clubs on the eastern side of the Arm, Fleming wanted to ensure that the people of Halifax would continue to have a place where they could enjoy being on the water, having a picnic, or simply taking in the natural surroundings of the North West Arm. Heather Watts and Michèle Raymond’s book Halifax’s Northwest Arm: An Illustrated History, opens a new window quoted Fleming as saying: “For a long time it has been a matter of great pleasure to me to see many of the citizens of Halifax innocently and healthfully enjoying themselves on my property.” (pg. 53). Unfortunately, a few reckless users caused damage to the area, which prompted Fleming to later implement a permit to access the grounds at a cost of $1 per year.

Sir Sandford Fleming Park

Sometime around 1905, Fleming took his belief that Haligonians needed a natural, public space one step further. He approached the Halifax City Council with an offer to donate 100 acres of his land on the North West Arm to be used as an official public park. The offer was largely ignored until 1907 when mayor Robert MacIlreith and A.M. Bell, the president of the Board of Trade, sat down with Fleming to discuss the details. Upon a meeting with the council, an Act for the Establishment of a Public Park for the City of Halifax was created. It was proposed that the space would be called Sir Sandford Fleming Park. But of course, these things take time, and while the planning began to take shape, Fleming got yet another idea.

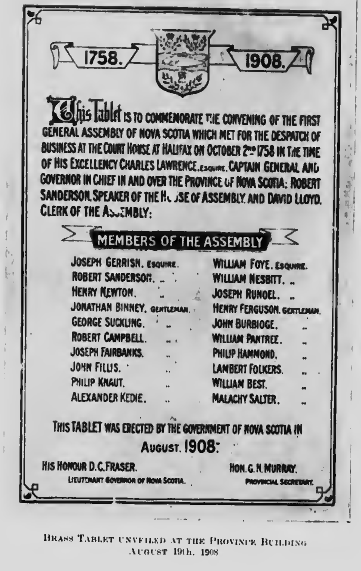

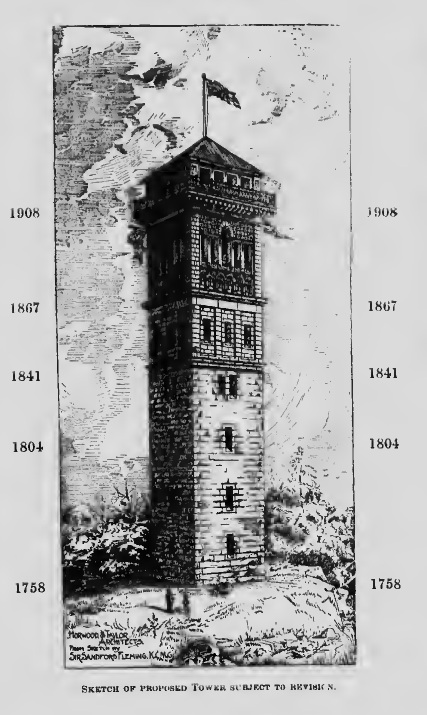

Over a century earlier, on October 2, 1758, the first Legislative Assembly met in Halifax. As representative government under the wing of the British Monarchy, this first meeting was effectively the beginning of the Parliamentary Government in Canada and was a significant moment in Canada’s colonial history. The approaching 150th Anniversary of this event was brought to Fleming’s attention by John Neville Armstong, a member of the legislative council. A firm believer in the strength of the British Empire, Fleming felt this anniversary required acknowledgment. In June of 1908, he wrote to Adam Crosby, the new mayor of Halifax, stating he wished for a tower to be built on the North West Arm:

…an ornamental edifice, imperial in its character, which would embody all the great historical associations of Halifax and Nova Scotia… For myself I would merely say that circumstances have placed in my possession an ideal site for the proposed monument, with land adjacent thereto, which may be used for a public park. As an earnest of my sincerity I offer both to the City free of charge. I will only add that I shall feel rewarded by the acceptance of the gift…

Fleming also proposed that the laying of the tower’s cornerstone could act as the opening ceremony for the park. City Council was wary. The expense of a monument such as Fleming described would be great, estimated between $10,000-$15,000. Even Lieutenant Governor Duncan Fraser, who sat on the 150th Anniversary Council, was not in favour of the idea. As word got out about Fleming’s tower, the people of Halifax also began to complain. Citizens wrote to the local papers voicing their disapproval: the tower would cost the taxpayers too much money, even if the land was included for free.

But Fleming wouldn’t take no for an answer.

To fund the tower, Fleming approached the recently formed Halifax branch of the Canadian Club. The Canadian Club was an organization that hosted discussions and lectures on specifically Canadian issues, as well as promoting other activities like archaeological studies, tours, and sponsoring Canadian citizenship. Fleming presented a letter to the Club asking members from across the globe for financial assistance in funding the tower; he himself was prepared to donate $1000. The Club committed itself to the cause, and in time raised some $23,000 to construct the tower. With the money raised, how could the city say no?

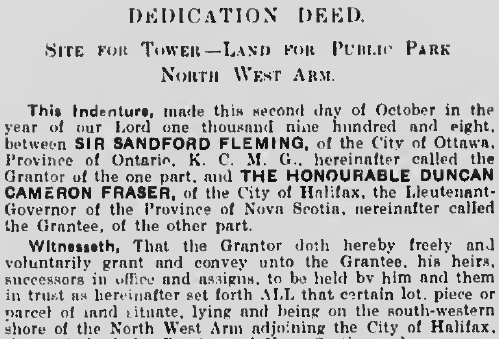

In the end, Fleming got exactly what he wanted; the cornerstone for the Memorial Tower was laid on a hill near the shore of the North West Arm on Fleming’s donated land. The stone was placed on October 2, 1908—150 years after the first seating of the Legislative Assembly. A copper box was buried beneath the stone, containing local newspapers, the Canadian Club Constitution, debates from the Legislative Assembly, and more. Lieutenant Governor Fraser was given the deed to the park property to hold in trust until such time that the tower was complete.

The Memorial Tower

To finalize the concept of the Memorial Tower, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada held a competition and awarded prizes for first, second, and third place designs. Ultimately, the Canadian Club chose a design by local firm Dumaresq & Cobb of Halifax, which would be constructed by S. M. Brookfield. Though Fleming had his own ideas for the design of the tower—one that told a story about the history of Nova Scotia and its part in Canadian government—his concepts were gradually set aside to make way for a simpler design.

The Tower includes three sections: an entrance level, an upper chamber, and an observation deck. The base of the Tower was constructed of locally sourced ironstone, with accents in granite. Granite was used to creating the front entrance, as well as the four archways on each side of the upper bell tower. Balconies were added to each side of the belfry to enable people to see the surrounding area with as little obstruction as possible. When complete, the Tower was thirty feet wide and stood 120 feet from the ground, plus an additional 70 feet above sea level.

Many gifts were presented to go with the tower. In 1913, two ten-foot bronze lions made by sculptor Percy Bentham were donated by the Royal Colonial Society. Other provinces and countries from as far away as New Zealand made donations of carved panels for the interior of the Tower, each said to be made from materials native to their region.

The dedication and grand opening

On August 14, 1912, the Memorial Tower had its grand opening, and GRAND it was.

The dedication of the Tower and the significance it symbolized for the British Empire had gathered royal attention. The Duke of Connaught, the youngest son of Queen Victoria, attended the ceremonies with his family and assorted government and military personnel. In addition, representatives from several Canadian provinces, and other countries in the British Empire, also made their way to Halifax for the event.

A children’s choir opened the festivities at the Tower, followed by speeches by the High Commissioner for Australia and the president of the Canadian Club. Gifts were bestowed upon the royal visitors, and a luncheon was held for a few select guests at the Waegwoltic, which had been decorated in thousands of red, white, and blue lamps. A regatta was held as part of the celebrations, with many boats and ships decorated for the occasion. One vessel even featured a miniature version of the Memorial Tower. As night fell, bonfires were lit on the western shore of the North West Arm that was said to blaze from “…Dead Man’s cave in the north to the grounds of F. B. McCurdy, M.P. in the south.” (Halifax Herald, August 15, 1912, pg 1). Lomer Gouin, the Premier of Quebec, said of the sight: “It is the best marine illumination I ever saw… I’m glad I came from Quebec to see it and to take part in the proceedings at the memorial tower. This illumination on the Arm surpasses anything of the kind I have ever seen.”

And so, Sir Sandford Fleming got his Tower, and Halifax got its park.

Looking forward

Above Photos by V Messervey, Dec 31, 2021.

Sir Sandford Fleming Park and the Memorial Tower were incredible gifts to the people of Halifax. The Halifax Regional Municipality has continued to dedicate financial and physical resources to ensure it remains a beautiful public space for both locals and visitors to enjoy.

However, in recent years many citizens have voiced their concerns over the condition of Fleming Cottage, the small dwelling Fleming had built on the property as a home for his gardener. In later years, Fleming’s daughter also lived in the house. The cottage is of particular historical significance as it is believed to be the place Fleming drew his last breath after falling ill with pneumonia in the summer of 1915.

Understanding its historical significance, the cottage was purchased by the City of Halifax in 1948, and the site was declared a Municipal Heritage Building in 1985. This designation, however, is not without its own need of improvement, as the Registered Heritage Property sign on the building misspells Fleming’s name and is dated incorrectly. There was a time when tenants lived in the cottage, but it has been empty for several years and is currently boarded up.

At one point, a proposal was set to go before the Municipality to conduct restoration of the cottage, but in May of 2019, a piece of land thought by many to already be a part of Sir Sandford Fleming Park was put up for private sale. The Municipality of Halifax worked out a deal to purchase the one hundred thousand square foot lot to ensure it would become an official part of Sir Sanford Fleming Park and save it from private development. But the price tag for the land was high—$990,000. This unexpected cost, combined with the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020, put on hold any discussions regarding the repair of the cottage.

The welfare of the building falls under the jurisdiction of the Halifax Parks Department. When contacted for an update, Parks Department Manager Ray Walsh stated that though he could not give specific details, District 9 Councilor Shawn Cleary does intend to bring a motion forward to council sometime this year that addresses a restoration effort for the Cottage.

With any luck, the near future will breathe new life into this part of Halifax history, and the people of Halifax will “healthfully enjoy themselves” in an even more beautiful Sandford Fleming Park.

Library Resources

Books

“Time Lord, opens a new window” by Clark Blaise, 2000, Ref 389.17 B635t

“Submission Historic Sites and Monuments of Canada Sir Sandford Fleming Park & Memorial Tower Historical & Cultural Landscape,, opens a new window” by Brian Cuthbertson and John Zuck and Associates, 2003, Ref 971.6225 C988s

“Man of Steel, opens a new window” by Hugh MacLean, 1969, Ref 921 F59mS

“Sketches and Traditions of the Northwest Arm, opens a new window” by John W. Regan, 1978, Ref 971.622 R33s 1978

“Hail to the Chief! The Life of Sandford Fleming Revisited, opens a new window” by Jay Underwood, 2011, Ref 625.10092 F598u

“Halifax’s Northwest Arm: An Illustrated History, opens a new window” by Heater Watts and Michèle Raymond, 2003, Ref 971.6225 W349h

Newspapers

Halifax Herald:

“Great Events in Our History” August 13, 1912, page 1-2

“The Memorial Tower: What It Is” August 13, 1912, page 1-2

“The Dedication of the Memorial Tower and the Illumination of the North-West Arm Tonight” August 14, 1912, page 1-2

“The Waters and the Heaves Illuminated by Red Light Bonfire, The Torch” August 15, 1912, page 1-2

“’Twas a Busy and a Pleasant Day for Their Royal Highnesses in Halifax” August 15, 1912, page 1

“One of the Great Men of Canada Dead” July 22, 1915, page 1,4

Online resources

CBC News: $2.3M Fleming mansion for sale in Halifax, opens a new window

Merriam Webster: Dingle, opens a new window

Saltscapes: The Dingle , opens a new window

Canada’s Historic Places: Fleming House , opens a new window

CTV News: Former cottage of Sir Sandford Fleming falling into disrepair, opens a new window

Government of Canada: Intercolonial Railway, opens a new window

Parks Canada: Memorial Tower National Historic Site of Canada, opens a new window

Canadiana Online: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Representative Government, opens a new window

Library of Congress: Panoramic View of the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia 1879, opens a new window

Library and Archives Canada: Portrait of Engineer Sir Sandford Fleming, opens a new window

Historica Canada: Sir Sandford Fleming , opens a new window

Canada’s Historic Places: Sir Sandford Fleming Cottage , opens a new window

The Canadian Encyclopedia:

The Canadian Encyclopedia: Imperialism, opens a new window

The Canadian Encyclopedia: Invention of Standard Time, opens a new window

The Canadian Encyclopedia: Responsible Government, opens a new window

The Canadian Encyclopedia: Sir Sandford Fleming, opens a new window

Halifax Municipal Archives:

“Plan of Property of Sir Sandford Fleming KCMG on North West Arm known as the Dingle Lands - October 1908” Halifax Municipal Archives, 102-14B.24

Nova Scotia Archives:

Canadian Club of Halifax fonds, opens a new window

The Royal Engineers in Halifax, opens a new window

Tom Connors: 'The Old Sport', opens a new window

Ray Walsh, Manager, Halifax Parks Department

Jesse Morton, Planner II, Halifax Heritage Planning & Development

Add a comment to: Sir Sandford Fleming Park and the Memorial Tower: A Brief and Not at All Definitive History