Written and compiled by Halifax Public Libraries' Local & Family History Team

What is Heritage Day?

Celebrated on the third Monday in February, Nova Scotia Heritage Day is a provincial holiday that seeks to celebrate its significant people, places, and events. Each year a new honouree is highlighted for their contributions to Nova Scotian history and culture.

This year on Monday, February 20, 2023 we will commemorate the life and the cultural legacy of Mi'kmaq poet Rita Joe.

Who was Rita Joe?

Rita was born in Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia in 1932 to Joseph and Annie Bernard. Annie passed away when Rita was only five, leaving her father to raise Rita and her siblings.

Rita's young life was unsettled. For the next five years she lived with a series of family members, friends, and in foster homes. She experienced many hardships during this time. At age nine she was reunited with her father, two of her brothers, and her sister. However, tragedy soon struck in 1942 when Rita's father became sick with pneumonia and died. After her father's death, Rita was sent to live in Oxford Junction, despite her father's dying wishes. Alcoholism played a prominent factor in the home where she lived, and she spent much of her time there living in fear of what might happen to her.

On occasion, Indian agents would come to the house looking for Rita to take her away to a residential school, but her foster parents told her to hide from them. By age twelve, Rita decided she could not stay where she was. She wrote to the local Indian agent herself and asked him to take her to the Shubenacadie Residential School. Rita's experience at the school left her with mixed emotions. While some of the nuns who ran the school were kind and taught the students valuable skills, many were very unkind:

"It is true that bad things happened while I was there. You can't help having a chip on your shoulder if you are told, military style, when to go to the bathroom, when to eat, when to do this and that, when to pray. We were even told when to yawn and cough. Children can't help themselves when they cough..." (Joe, p. 50).

Many students were subject to mental and physical abuse, and they were forbidden from participating in their own Mi'kmaq culture:

"We were not allowed to express our Native language, culture and spirituality, and these things are very important to us. Some of us carry that on our shoulders still; our anger is still there" (Joe, p. 48).

At age sixteen, Rita left the school. The nuns had given her two options: she could go to British Columbia to potentially become a nun herself, or they could get her a job at the Halifax Infirmary. Rita jumped at the chance for employment, and was off to Halifax the following day.

In Halifax, Rita learned many lessons about the world, but she also taught them right back. In her autobiography, Rita recalls a time when she and two of her friends were walking down Barrington Street and a man shouted "Squaw!" as they walked by. She asked him who he was shouting at and as he indicated one of her friends. Rita swung at the man with her purse, hitting him with the large brass buckle on the outside. "If you're calling my friend a squaw, we're all squaws, because we're all Native." (Joe, p. 62)

Rita did not stay in Halifax long. She had a child while living in Halifax, which her sister adopted. After the baby was born, she moved to Boston where she had two more children in ill-fated relationships. Eventually she met a Mi'kmaq man from Pictou Landing and they became engaged. However, this marriage would never occur, as Rita soon met Frank Joe, another Mi'kmaq man from Cape Breton. She met Frank in a restaurant in Boston while dining with her then-fiancé. After dinner, Rita noticed she had lost her keys. As it happens, Frank had picked them up. After meeting with her on a few occasions, Frank asked Rita to marry him, and after some consideration, Rita said yes.

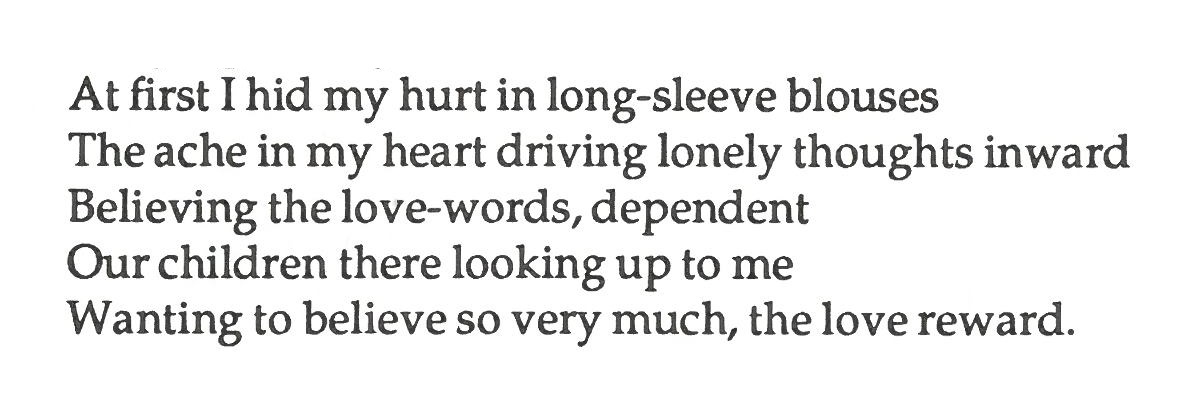

By the mid-1950s, the family had moved back to Nova Scotia. Soon Rita and the children moved from Halifax to Eskasoni while Frank continued to work in Halifax, and eventually Sydney. They had very little money and suffered many hardships. Rita had several health scares that put her in the hospital, and Frank began to drink, which lead to physical abuse against Rita.

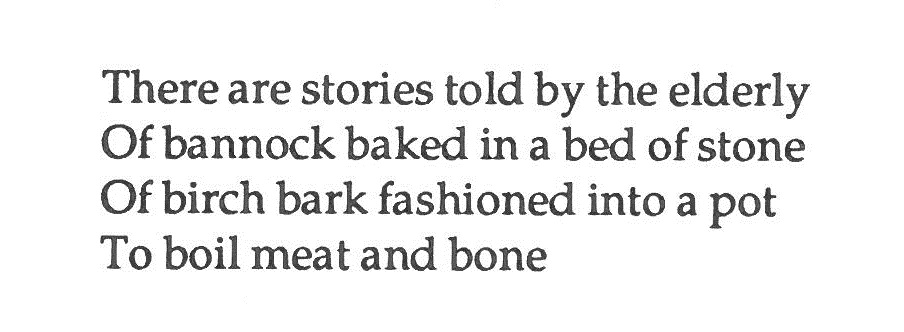

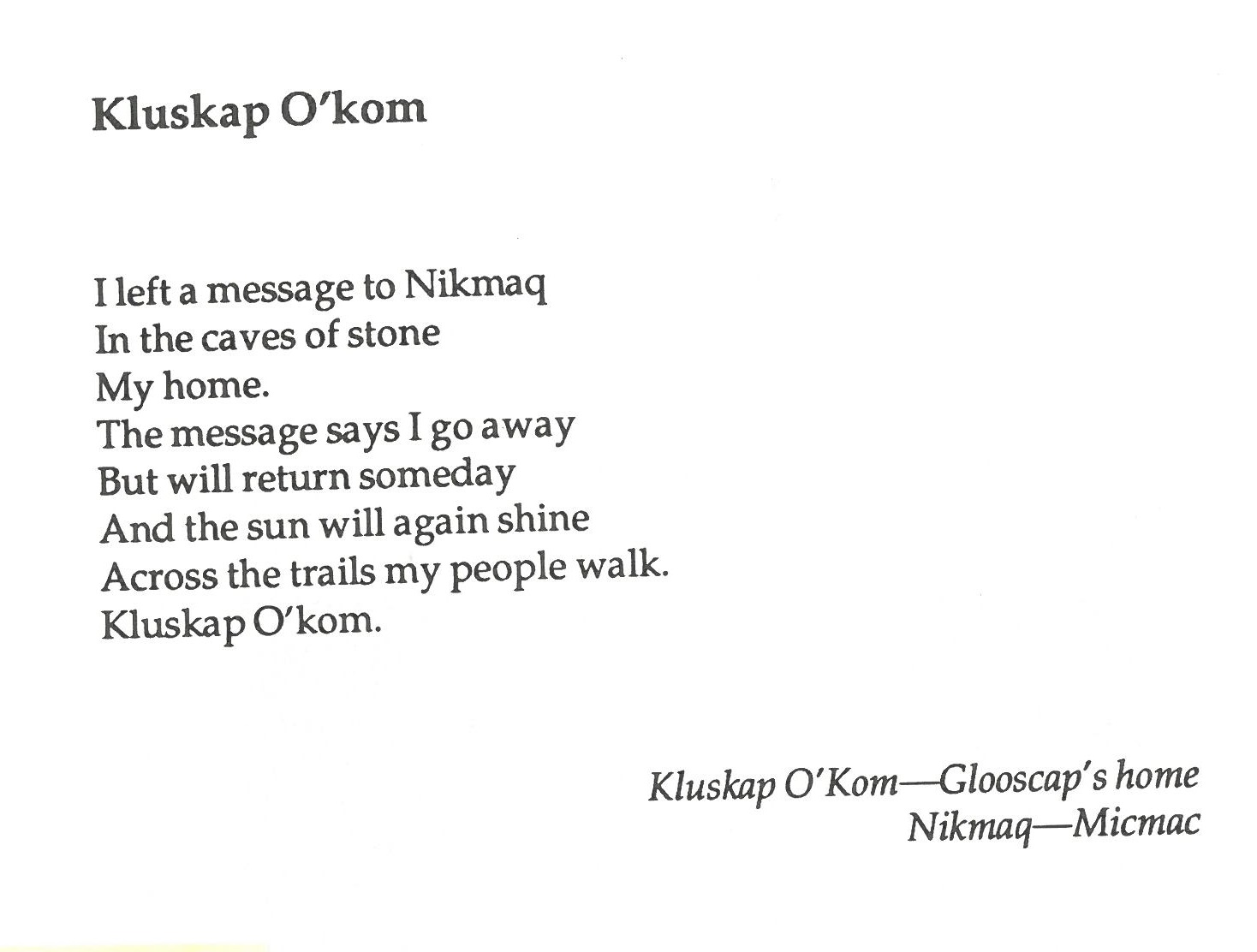

When Rita was in her thirties, she began to write. When Frank asked what she was going to write about, she said "We have to tell our lot... We have to be the ones to record our words." (Joe, 97) Her first poem was published in the local Mi'kmaq newspaper. She received a multitude of compliments and praise from the community, and so she continued to write both poetry and short stories. In time, she began to write a monthly column for the Micmac News entitled "Here and There in Eskasoni". The articles discussed indigenous stories, medicines, and ways of life.

Rita's time with the paper was cut short, however, when Frank told her he was seeing another woman and wanted a divorce. Rita went to the woman's home and held her against a wall. Rita was charged with breaking and entering as well as assault. In her autobiography she stated: "I shouldn't have done what I did; I knew better and I've always known better." (p. 106). As this was her first and only offense, she was only held in jail for one night and given a fine of $25. Frank picked her up from the arraignment. Not only did Frank's affair end, but Rita managed to turn a regrettable event around. Rita visited the woman later and they had a serious talk about their situations. In the end, they parted as friends. In time, Frank attended university and received both Bachelor of Education and a Sociology degrees. It was this education - along with support from the community - that helped him see the errors of his ways. He gave up drinking and did his best to make up for the more difficult times in their marriage.

Despite no longer working for the newspaper, sRita continued to write her poems. In 1974, she entered a literary contest put on by the Nova Scotia Writers' Federation in Halifax. She did not tell anyone that she had submitted her poems, as she did not want anyone to know if she did not succeed. Much to her surprise, Rita received a call that she had won.

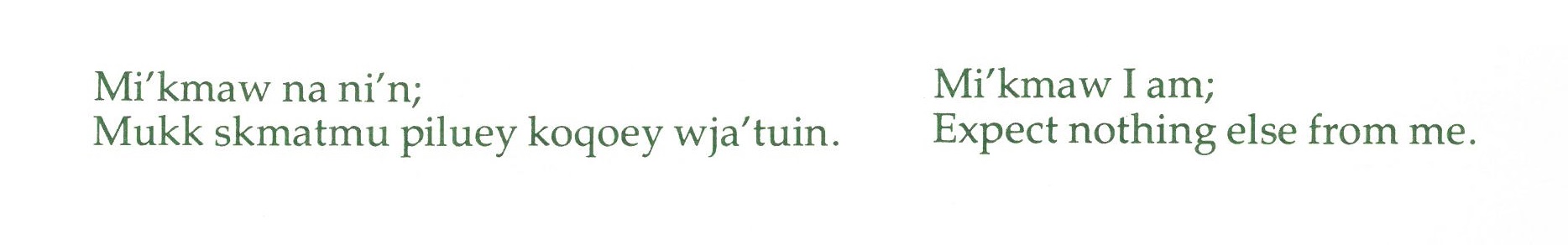

In 1978, Rita published a book of her writing, Poems of Rita Joe. She describes it as her "cry and look at me" book: "In it I talked about honour and good intentions. If I said something negative, I followed it up with something positive. I was still afraid when I wrote that first book." (Joe, 117) She began speaking in public schools, and was later contacted by the Canada Council to speak to universities, women's groups, and other organizations. Her follow-up book, Song of Eskasoni, was published in the late 1980's. Rita says the book is "... more assertive. ... I vented my anger about what the world chooses to deny of my peoples' expression and history. I talked about what I knew to be true. In this second book, I was at war - but it was a gentle war." (Joe, p. 128)

Everything seemed to be coming together for Rita after a long time of hardships. But in the summer of 1989 tragedy struck. On a trip to Maine for a speaking engagement, Frank passed away. Though her heart was broken, Rita took comfort in the support that was offered to her by her family and her community. She also saw it as another opportunity to tell her story. Her third book, Lnu and Indians We're Called, was published in the early 1990's. Rita considered this book a dive into her traditional language and her own spirituality.

Just before Christmas 1989, Rita received a phone call. The caller told Rita that through her writing and public speaking she was considered an ambassador for her people, and that for her efforts she was going become a member of the Order of Canada. This honour prompted her daughter to call her "Mother Ambassador." It was a ceremony full of pride, pomp, and protocol. In 1991, she received another honour: the chance to meet Queen Elizabeth II in Ottawa. At this opportunity, Rita could not help but break the rules that had been laid out for her:

I stood before the Queen and waited for her to offer her hand, like we had been told to do; but when she did, everything went out the window. I looked at her and saw that I was looking at another person, one-on-one. That is the Indian way of thinking: The other person is on the same level as you. I experienced a good feeling from the Queen, so I looked her right in the eye and asked: "How are your grandchildren?" She was flustered because I had broken protocol; I wasn't supposed to ask a question. But in a moment she said, "Oh, they're fine!" in an eager voice. She acted like a grandma. I felt happy after that.

(Joe, p. 157)

Rita would go on to be a member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada, and receive the National Aboriginal Achievement Award. She would also received honourary doctorate degrees.

In the early 1990's, Rita was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, but this did not stop her writing. Rita began to focus on writing songs as well as poems. In 1996, she published her autobiography Song of Rita Joe and in 1999 another book of poetry called We Are the Dreamers. Her works were also published in a number of literary anthologies.

Rita continued to write until the day she died - March 20, 2007. The Blind Man's Eyes - a collection of new and selected poems - was published posthumously in 2015.

Why is Rita Joe important to Nova Scotia?

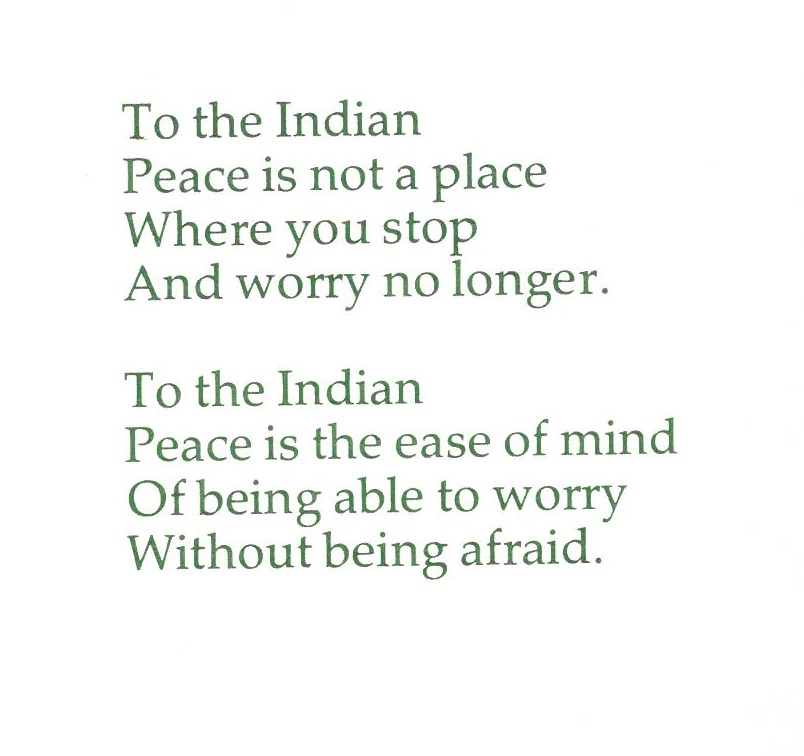

Rita used her poetry as a way to tell her own story—the good and the bad. She used her words to speak her truth and to talk about her people, her culture, and her language. In doing so, she helped promote the Mi'kmaq experience in Nova Scotia and greater North America.

Congratulations to Rita Joe, Nova Scotia's Heritage Day Honouree.

Books by Rita Joe:

Books and films featuring Rita Joe:

Sources:

Nova Scotia Heritage Day, History

Rita Joe, Canadian Encyclopedia

Add a comment to: Nova Scotia Heritage Day 2023: Honouring Mi’kmaq poet Rita Joe