Written by Zso, staff member, Halifax Central Library

Originally published October 2022

I was supposed to be cataloguing the pile of newspaper clippings and other documents spread out on the scarred meeting room table, not reading them. But the story of a valiant little bookstore’s fight against state censorship, taking place in a courtroom half-way across the country was too compelling to be simply sorted and filed away.

In 1994, I was working as an Archival Technician with the Manitoba Gay and Lesbian Archives which, at that time, was little more than a closet full of bankers boxes in the Gay/Lesbian Resource Centre (as it was then known) located at Confusion Corner in Winnipeg, Manitoba. I had been hired to reorganize the Archives on a grant-funded, one-year term. Among the posters, pamphlets, newsletters, and recorded interviews were a mess of newspaper articles documenting 2SLGBTQIA+1 history in Canada. I was mindful of my looming deadline every time my eyes lingered on the stories documenting the Little Sister’s case as it wound its way through the courts in Vancouver, British Columbia.

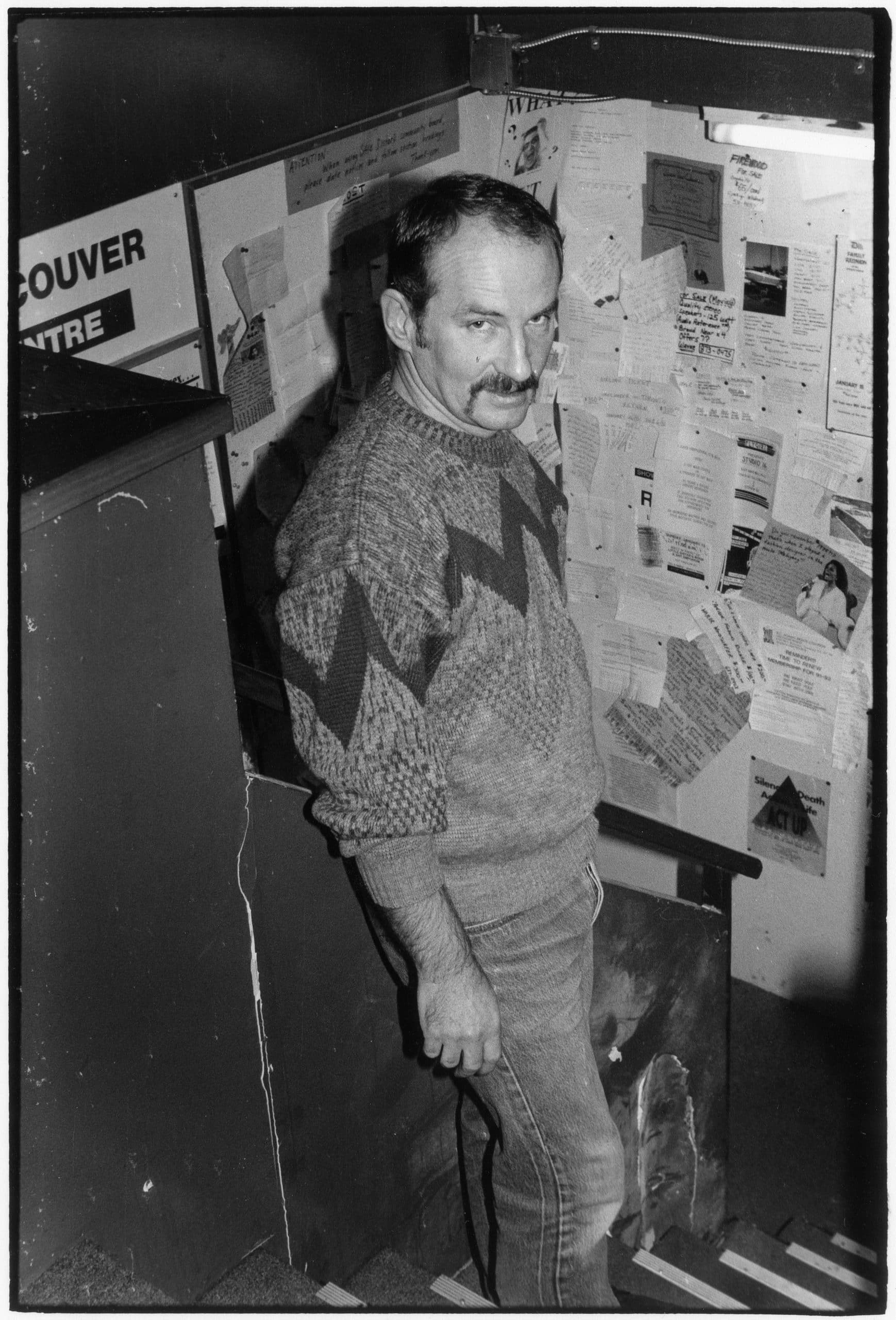

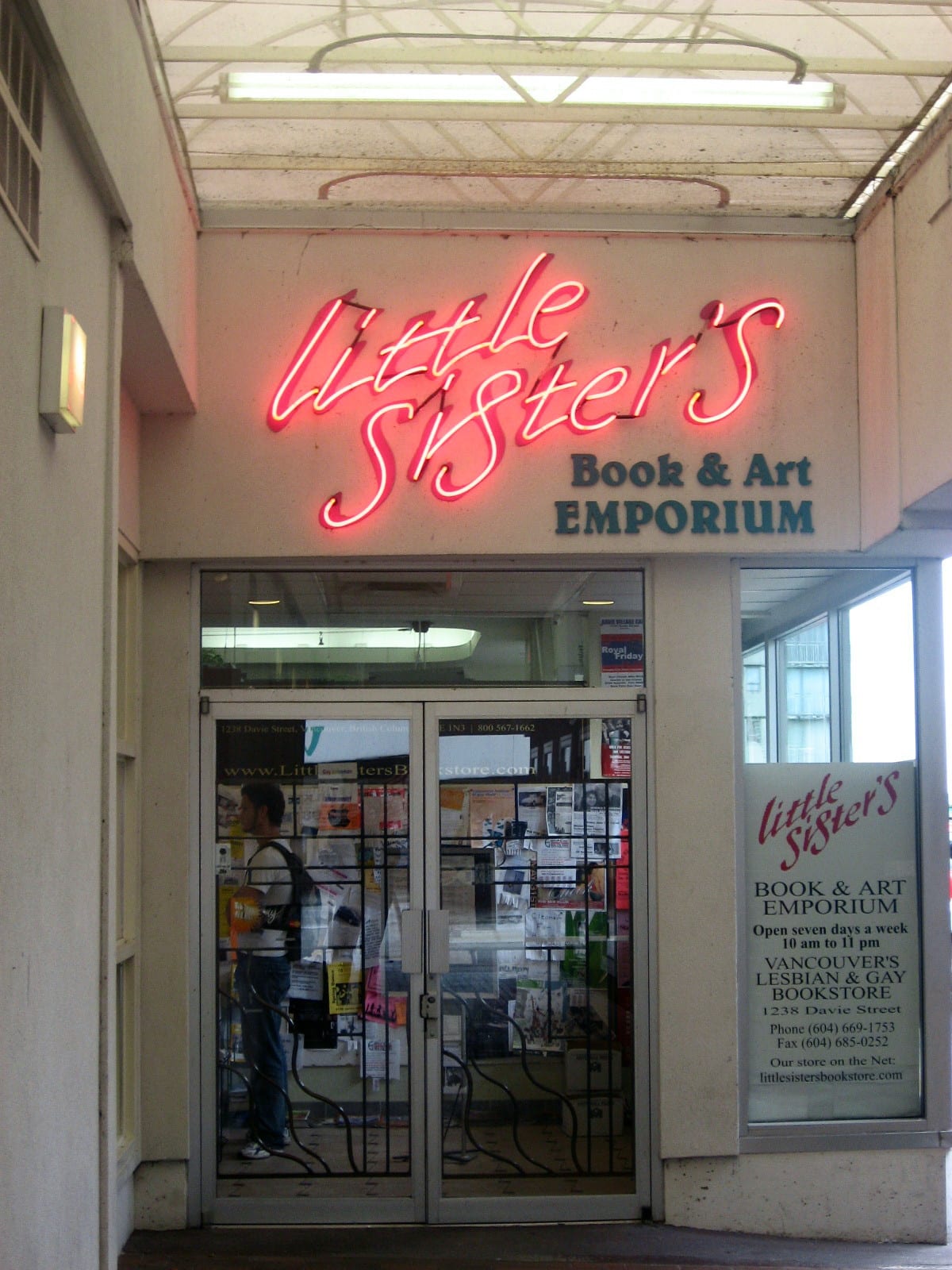

Little Sister’s Book & Art Emporium first opened its doors in 1983. In the early years, they quietly sold books, exhibited art, and briefly expanded to a small restaurant catering to the 2SLGBTQIA+ community in Vancouver. Within a few years, however, border officers with Canada Customs (now: the Canada Border Services Agency) began to take notice. By 1986, Little Sister’s was struggling financially and looking to recoup its investment in titles by Adrienne Rich, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Christopher Isherwood, just in time for Christmas. But the store’s Customs broker warned owners Jim Deva and Bruce Smyth that border officers had threatened to delay and detain future shipments of the “disgusting” material which Little Sister’s had been importing (Fuller and Blackley 6). On December 8th of that year, Little Sister’s received notice that Customs was holding back most of their Christmas stock. “That’s when we figured out they had the power to put us out of business,” said Deva of this moment (Babineau).

Although the routine seizure of printed material at the Canadian border started in the nineteenth century, it wasn’t until the 1970s that an explosion in 2SLGBTQIA+ creative production caught the attention of Canada Customs. Before 1985, laws which regulated books and magazines imported to Canada reflected a conservative bias that winked at depictions of straight sexuality while forbidding “immoral” or “indecent” content, including representations of queer sex (Cossman 49; Robertson 215). Legal Professor Brenda Cossman links an increase in censorship of this material to the emergence of the Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement in the seventies and eighties (45). Eventually, the Customs Tariff Act and its supplemental Memorandum D9-1-1 (which spell out what can be legally brought to Canada) were changed and Victorian standards of “decency” were swapped for obscenity, as defined by the Criminal Code.

Little Sister’s longtime store manager, Janine Fuller (with journalist Stuart Blackley), wrote the book on the store’s history. In Restricted Entry: Censorship on Trial, the authors describe the challenges of running the only 2SLGBTQIA+ bookstore in Vancouver. In the 1980s, Canadian 2SLGBTQIA+ bookstores reported that Customs officers seemed to pay particular attention to their imported material, exercising “prior restraint” and seizing items they suspected were obscene. Macho Sluts by Patrick Califa, was Little Sister’s most frequently seized title. That the book was detained and ultimately cleared on five separate occasions is suggestive of Customs’ practices when it comes to 2SLGBTQIA+ material (Fuller and Blackley 57).

As Fuller and Blackley point out, a criminal charge of obscenity is imposed by police and can be argued openly and fairly in a court of law. Customs’ “administrative censorship,” on the other hand, is not subject to the same oversight (Robertson 220-21). And in those days, when something was detained at the border, the responsibility for challenging its detention lay with the business that imported it. Never charged with any criminal offense, Little Sister’s owners wanted to overturn the Customs Act and Customs Tariff Act because they believed that these regulations were being applied in a discriminatory way, contrary to the Canadian Constitution (Fuller and Blackley 169). They further argued that this treatment was a violation of their right to freedom of expression under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. These claims were the basis of the legal challenge which Little Sister’s, with the support of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, brought to the B.C. Supreme Court in 1994.

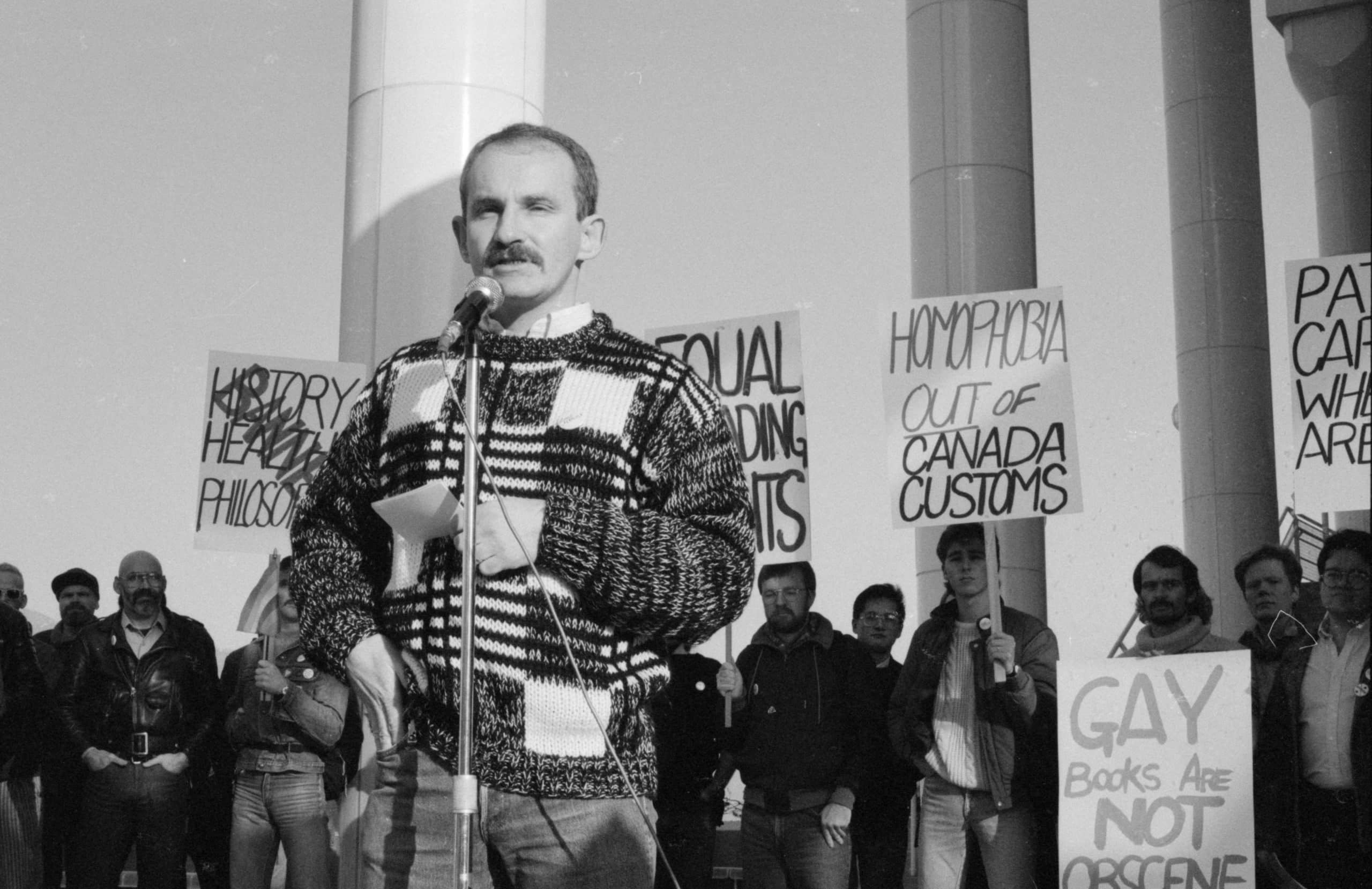

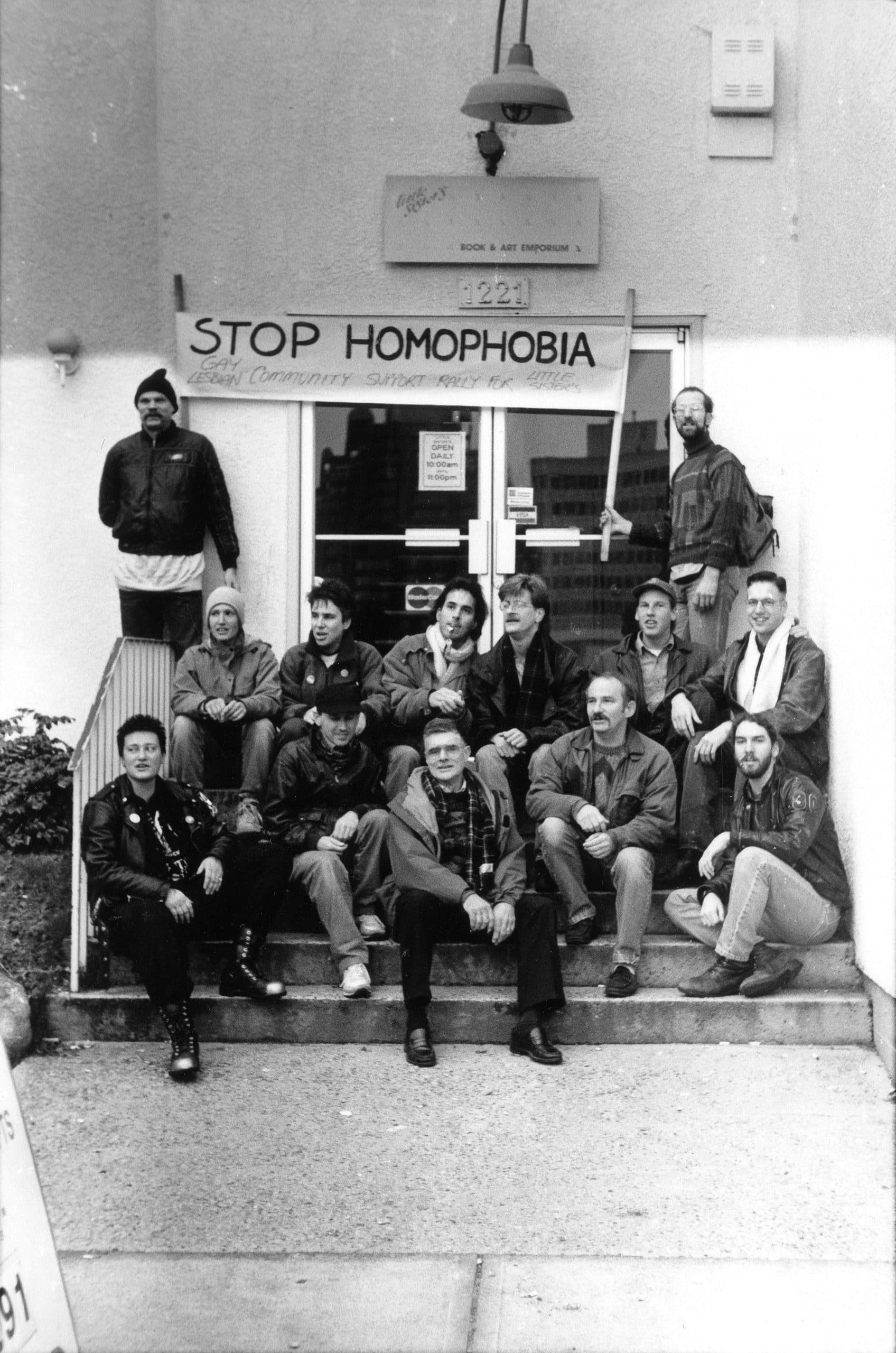

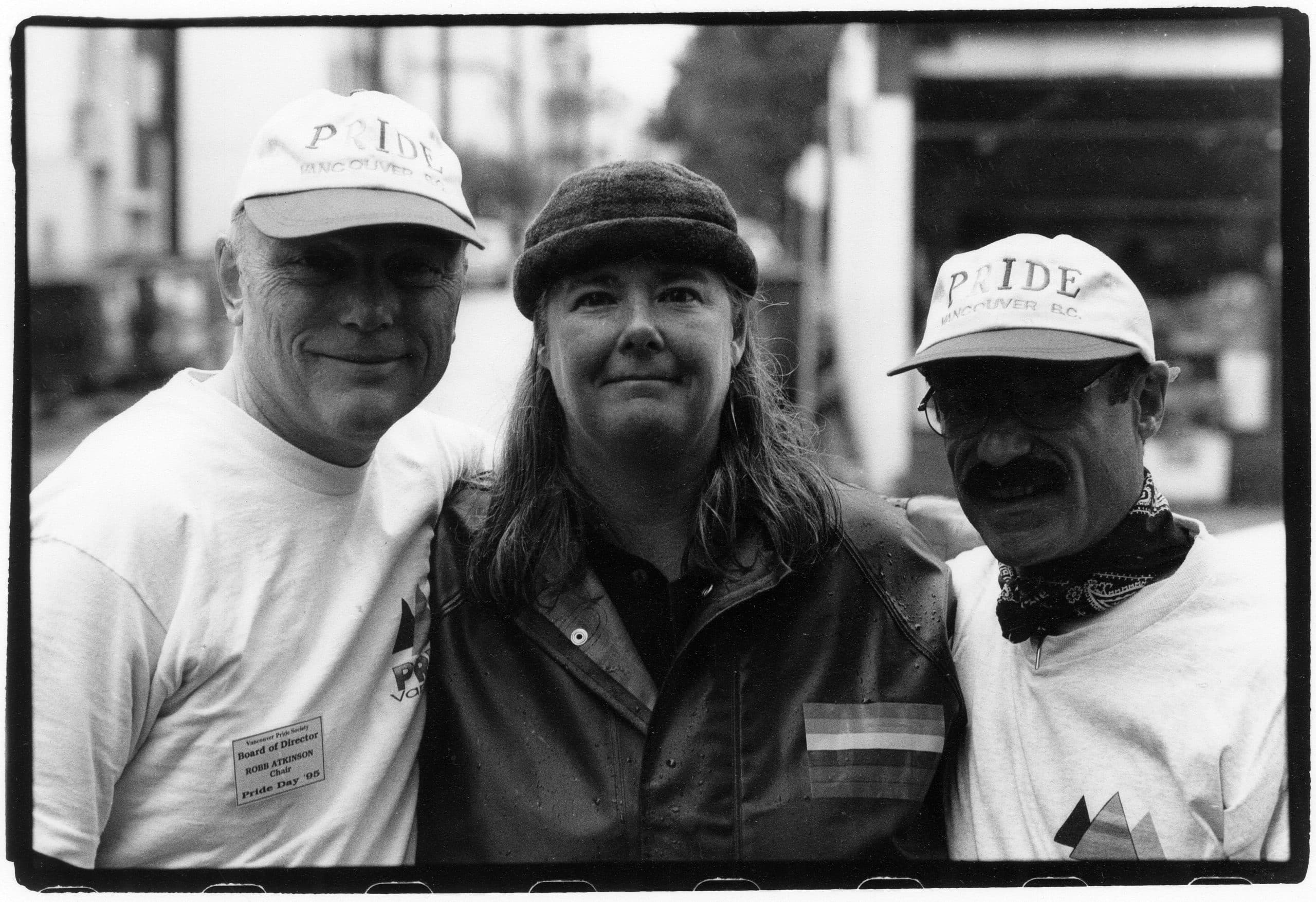

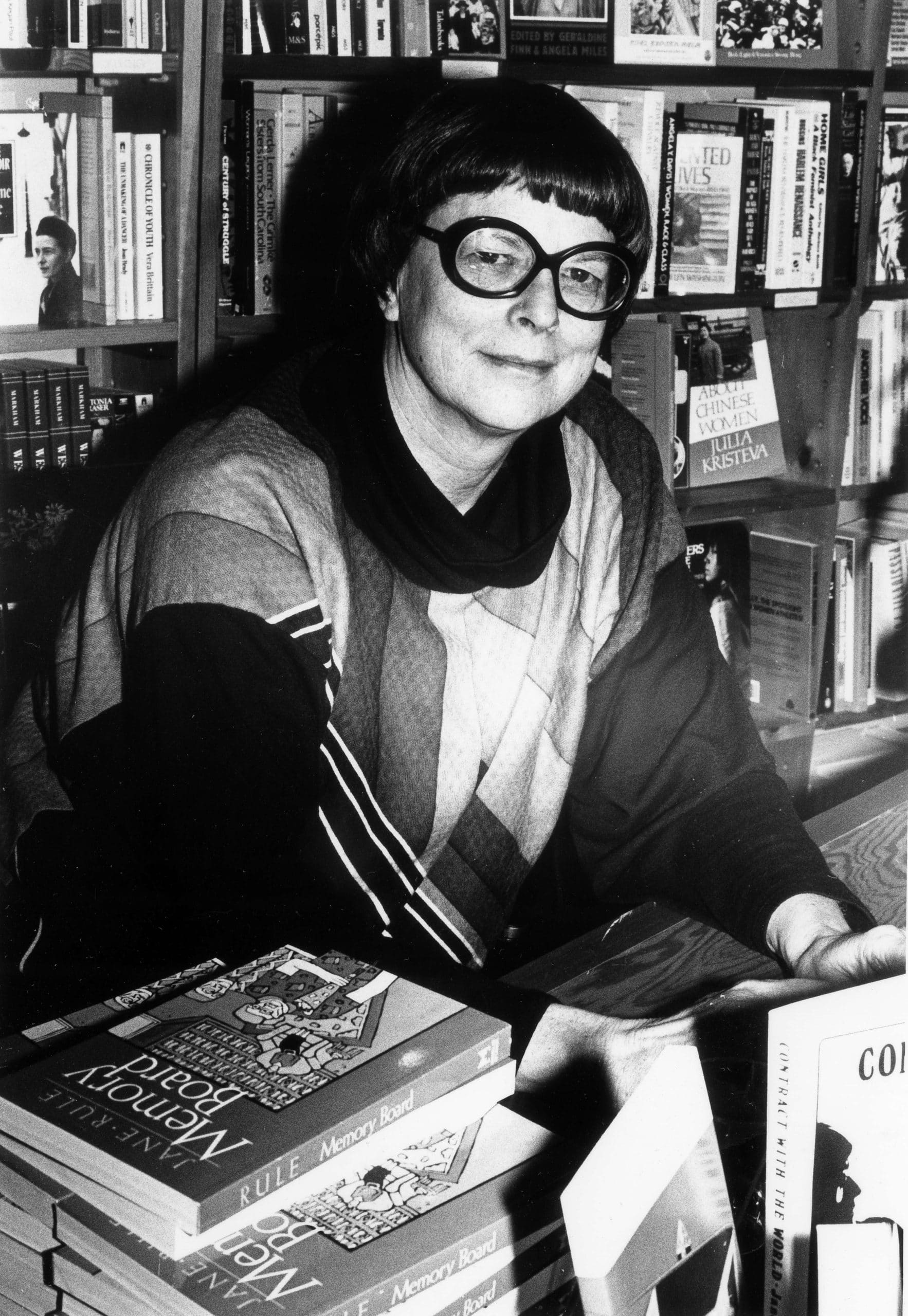

In their lawsuit against the Minister of Justice, the Attorney General of Canada, the Minister of National Revenue, and the Attorney General of British Columbia, Deva and Smyth were backed by lawyer Joseph Arvay with help from the Canadian, U.S., and international wings of PEN. Literary legends like Jane Rule, Patrick Califa, Nino Ricci, Michael Ondaatje, Timothy Findley, and Pierre Burton offered their assistance. At fundraisers, public rallies, and in the courtroom, Little Sister’s and their supporters pursued their fight against the censorship that was harming the community-based business and blocking the community’s access to the magazines, novels, and health care manuals that were stopped – and in some cases, destroyed – by Canadian border agents.

A little over a year later, in 1996, Justice Kenneth Smith issued his verdict. Although Little Sister’s did not get everything they wanted from the decision, Deva, Smyth, and Fuller could take some satisfaction from Justice Smith’s conclusion that Customs’ legislation had been misapplied in ways that infringed on the equality and freedom of speech of 2SLGBTQIA+ people (188). In his judgement, Justice Smith catalogued each Charter violation, including the targeting and excessive detentions of Little Sister’s imports and a stubborn practice of illegally seizing material geared to gay men. Significantly, the judge agreed with Little Sister’s that this last violation “constituted an embargo of ‘safe sex’ guidelines within Canadian homosexual communities at a time, in the context of the AIDS epidemic, when such guidelines have been particularly important” (Little Sisters v. SCBC 126). Justice Smith awarded court costs to the Little Sister’s team, who were granted an injunction against Customs’ discriminatory targeting of their store (Fuller and Blakely 195-96).

This was not the end of Little Sister’s fight against 2SLGBTQIA+ censorship. That came later, in 2007, when Canada’s Supreme Court overturned a British Columbia Court of Appeal case that awarded the bookstore $300,000 in costs to continue their legal fight against Canada Customs (Little Sisters v. Canada 2007; McCann 2007). Justice Smith’s injunction notwithstanding, Little Sister’s imports of 2SLGBTQIA+ material continued to be targeted for censorship by border officers. Like the B.C. Supreme Court, the Supreme Court of Canada has been unwilling to consider that a more systemic form of discrimination might be at play, instead insisting that Customs’ regulations were simply being misinterpreted (Little Sisters v. Canada 2000; Ryder). Without a legal fund, Little Sister’s had run out of time and money to prove that homophobic discrimination is a feature, not a bug, of Canada’s border regulations. It was a disappointing end to a long, courageous campaign.

Although their legal strategy ended prematurely, this does not diminish the importance of what the Little Sister’s team achieved. Legal precedents were made and border regulations were changed as a result of their actions. With few resources, a community bookstore managed to rally and sustain a decades-long operation to resist state censorship. Cossman observes that “censorship helped to mobilize a social movement which then contested the censorship” (66). Enduring financial hardship and three terrorist bombings, the store survives in its current location in Vancouver’s Davie Village area. “I think it will be here for the long term,” observes its current owner, Don Wilson (Zeidler).

Reflecting

In Restricted Entry: Censorship on Trial, the question, “should Canada Customs have the right to decide what Canadians read?” is treated as fundamental to Little Sister’s legal challenge (Fuller and Blackley 23). During the first trial, Jim Deva advocated for free access to literary material (24). His lawyer, Arvay, explained to the court that, for 2SLGBTQIA+ people, free expression includes honest depictions of 2SLGBTQIA+ lives, “yet honest depictions of lesbian and gay lives have traditionally been equated with, and condemned as, pornography” (59). On the stand, Canadian author Jane Rule testified:

We are a community speaking about our passion, our humanity in a world that is so homophobic, that it sees us as nothing but sexual creatures instead of good Canadian citizens, fine artists, and brave people trying to make Canada a better place for everybody to speak freely and honestly about who we are (78).

Though Little Sister’s original case concluded almost 30 years ago, these criticisms of the bias inherent in 2SLGBTQIA+ censorship remain relevant today.

According to Marcus McCann, a lawyer and part-owner of Toronto’s Glad Day Books – the oldest 2SLGBTQIA+ bookstore in the world – “approximately half of the most often challenged books in Canadian libraries are non-sexual LGBTQ-themed books: children’s books with queer and trans characters or themes” (2019). In 2019, eight of the ten books that made the American Library Association’s “Most Challenged Books” list featured 2SLGBTQIA+ content (Aviles). A couple of years later, out of the unprecedented 700 book challenges that the ALA documented in 2021, that ratio fell – just a little – to five out of ten (Dellatto). Echoing Justice Smith’s criticism from the Little Sister’s case, Maia Kobabe – author of one of the most frequently challenged books, Gender Queer – points out that censoring 2SLGBTQIA+ books is harmful, particularly to young people: “removing or restricting queer books in libraries and schools is like cutting a lifeline for queer youth, who might not yet even know what terms to ask Google to find out more about their own identities, bodies and health.” For McCann, this all goes to show that the censorship of 2SLGBTQIA+ material is not about protecting children or outlawing obscenity: “any idea that LGBTQ people can ‘clean up,’ presenting only non-sexual images and being safe from censorship, is bogus. Our lives continue to be so offensive that any depiction of them is still worthy of censorship” (2019).

Observing these library book challenges from across the border, we can see the truth in Mark Joseph Stern’s warning: “when censorship is permitted, gay books will be the first to go.”

The Little Sister’s case illustrates why conversations about free expression are best conducted in full view and with the active participation of the public. Brenda Cossman argues that there is value in challenging censorship and advocating for freedom of expression, regardless of the outcome. 2SLGBTQIA+ identity and community were developed alongside these public and private debates. Through their resistance to transphobic and homophobic censorship, the 2SLGBTQIA+ community has helped to make the broader society more inclusive by challenging assumptions about what is considered socially acceptable and by whom.

The freedoms we currently enjoy in Canada are not inevitable nor are they entirely secure. Whether or not we achieve the specific changes we want from these conversations, we can recognize that we – as individuals and as a people – are changed through these conversations. As the German novelist and Nobel prize winner Günther Grass wrote, “the job of a citizen is to keep [their] mouth open” (IFLA).

Further reading

Selected nonfiction reflecting the historical experiences of 2SLGBTQIA+ people in Canada.

Note:

- “2SLGBTQIA+” is used by Halifax Public Libraries as an umbrella term which includes those who identify as Two Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual (with the “+” added as a nod to other, related identities). In the 1970s-1990s, “gay” or “gay and lesbian” were terms more commonly used to name this community. In this article, I apply more inclusive language unless I am quoting someone else.

Works cited

Aviles, Gwen. “Eight of 10 Most-Banned Books Challenged for LGBTQ Content.” NBC News, 20 April 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/eight-10-most-banned-books-challenged-lgbtq-content-n1188041. Accessed 9 July 2022.

Babineau, Guy. “Little Sister’s: 25 Years of Determination: Look Back at Bookstore's Legacy of Defiance.” Xtra!, 22 April 2008, https://xtramagazine.com/power/little-sisters-25-years-of-determination-38322. Accessed 9 July 2022.

Cossman, Brenda. “Censor, Resist, Repeat: A History of Censorship of Gay and Lesbian Sexual Representation in Canada.” Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy, vol. 21, no. 45, 2013, pp. 45-66.

Dellatto, Marisa. “‘Unprecedented’ Book Ban Attempts In 2021—Many With LGBTQ Themes—Library Group Reports.” Forbes, 4 April 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/marisadellatto/2022/04/04/unprecedented-book-ban-attempts-in-2021-many-with-lgbtq-themes-library-group-reports/?sh=2af3cc8f5b52. Accessed 9 July 2022.

Fuller, Janine and Stuart Blackley. Restricted Entry: Censorship on Trial. Press Gang Publishers, 1996.

IFLA Advisory Committee on Freedom of Access to Information and Freedom of Expression. “Quotes on Intellectual Freedom and Censorship.” January 2007, https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/1722. Accessed 25 August 2022.

Little Sisters Book and Art Emporium v. Canada (Commissioner of Customs and Revenue). 1 SCR 38, Supreme Court of Canada, 19 January 2007, Supreme Court of Canada, (https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2337/index.do.

Little Sisters Book and Art Emporium v. Canada (Minister of Justice). 2 SCR 1120, Supreme Court of Canada, 15 December 2000, Supreme Court of Canada, https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/1835/index.do.

Little Sisters Book and Art Emporium v. SCBC. , no. A901450, Supreme Court of British Columbia, 19 January 1996, Supreme Court of British Columbia, http://egale.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Little-Sisters-SCBC-1996canlii3465.pdf.

McCann, Marcus. “Fifty Years of Defending Queer Expression: Glad Day Bookshop Celebrates a Milestone Anniversary.” Freedom to Read, 27 February 2019, https://www.freedomtoread.ca/articles/fifty-years-of-defending-queer-expression/. Accessed 9 July 2022.

---. “Little Sister’s Declares Defeat in the Wake of 7-2 Supreme Court Ruling.” Xtra*, 18 January 2007, https://xtramagazine.com/power/little-sisters-declares-defeat-in-the-wake-of-7-2-supreme-court-ruling-39253. Accessed 9 July 2022.

Robertson, James R. Obscenity: The Decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Butler. March 1992, https://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/bp289-e.htm. Accessed 21 June 2022.

Ryder, Bruce. “The Little Sisters Case, Administrative Censorship, and Obscenity Law.” Osgood Hall Law Journal, vol. 39, no. 1, Spring 2001, pp. 207-227.

Stern, Mark Joseph. “Count On It: When Censorship Is Permitted, Gay Books Will Be Censored.” Slate, 11 July 2014, https://slate.com/human-interest/2014/07/censorship-leads-to-banning-gay-books.html. Accessed 9 July 2022.

Zeidler, Maryse. “25 years ago, This LGBT Landmark in Vancouver Took on 'Big Brother' and Won.” CBC News, 20 October 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/little-sisters-cbsa-challenge-1.5325456. Accessed 9 July 2022.

About the staff blogger

Zso is a Branch Services Lead with Halifax Public Libraries.

Add a comment to: Mouths Open: On 2SLGBTQIA+ Censorship