Created by the Atlantic Spinners Art and Dance Society

Created by the Atlantic Spinners Art and Dance Society

Skip to Topic

- Municipal Proclamation

- A message from the Atlantic Spinners Art and Dance Society President

- Rangoli: The powder art

- Bhavai folk theatre

-

Clay art and storytelling: Ganesha

- Indian dance

- Indian textiles and clothing

Municipal Proclamation

Read the Halifax Regional Municipality Indian Independence Month Proclamation by Mayor Mike Savage

A message from the Atlantic Spinners Art and Dance Society President

Mahnaz Roshan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qs-RXyqmgBE

“I love my country, and I am proud of its rich and varied heritage” – Indian National Pledge

“I love my country, and I am proud of its rich and varied heritage” – Indian National Pledge

Atlantic Spinners Art and Dance Society, opens a new window’s goal is to support, promote, and develop art through artistic collaboration by preserving and practicing the ancient styles of art from around the world. We will achieve the above through promoting diversity and inclusion of the community at large, through cultural events and educational workshops. Our goal is to collaborate with partners who share the same vision and values and have a desire to promote art and culture all over Canada.

Citizens from all over the world have adopted Halifax Regional Municipality as their home, and Indians are part of this diverse population.

Please take the time to acknowledge their contributions to HRM as employees, volunteers, family members, and neighbours, by declaring Indian Independence Month in August. Indians living in HRM also contribute to the arts through food, culture, clothing, music, and art, working side by side with members of the community. Atlantic Spinners recognizes the rich culture and heritage of India and would like to celebrate the liberation of Art and Artistic expression India received on August 15, 1947. The diverse art and culture of India has been influenced from across the world, by a history that is centuries old.

Rangoli: The powder art

by Geervani Gangaraju

Ragoli/ muggu is an age-old tradition in India that has been passed down over several centuries.

In south India, it is part of everyday life. The day begins with cleaning the previous day's rangoli and making a new one on one’s front porch. It is a welcome sign, an invitation to bring positivity and abundance into the home. Imagine walking into a house and being welcomed by a beautiful handmade design. Just the thought can bring a change in your energy or feelings. And if you talk about festivities, it is hard to imagine a festival without elaborate and colourful Rangoli!

Bhavai folk theatre

by Dhwani Desai

Hello Friends,

My name is Dhwani Desai and I am a Research Associate at Dalhousie University in Halifax and today, we are going to get culturally acquainted with Bhavai, a traditional street or folk theatre form from Gujarat in India.

A brief history

Gujarati street or folk theatre commonly known as Bhavai, has a rich and popular history dating back to the 14th Century AD. Its genesis is an interesting story.

Somewhere in the 14th Century AD, in a village in north Gujarat, the young daughter of the village headman belonging to the Patel community (basically farmers and cowherds) was kidnapped by a Muslim subedar (district head). The family went to their priest named Asait Thakar for help.

Asait Thakar went to rescue the girl saying that she was his, a priest’s daughter—priests were considered the higher caste in those days. The subedar asked him to prove it by sharing a meal with the girl—in those times, caste based segregation meant that priests could not share meals with farmers. To save the girl’s life, Asait Thakar shared a meal with her. He managed to save the girl, but he was outcast from his own community.

He then formed his own troupe of artists and started doing street plays which came to be known as Bhavai or Veshas, Gujarati words that literally translate to “spectacle” and “make-up” or “costume”. The plays and the troupes that performed them grew so popular that they eventually formed a separate community of traveling theatre artistes called Bhavaiyyas or Tragalas.

The format

The Bhavai format incorporates elements of singing, dancing, dialogues and verses to convey a simple story with a lot of locally flavoured humour.

Every Bhavai performance starts with a narrator or narrators invoking Ganesha - the elephant god believed to remove obstacles from every endeavour - and announcing the title of the particular vesh or skit. The narrators – Ranglo, the hero, Rangli the heroine and Vidushak or the jester - keep the story progressing with their banter and humour. The other common feature of all performances is the group of musicians playing the dhol , tabla or pakhavaj (types of Indian drums), cymbals and the Bhungal, which is a 6-foot long thin trumpet-like horn made of copper.

Bhavai performances or veshas traditionally tackled themes related to local history, religious figures and satire, or social commentary on taboos or issues of discrimination. The scope of the veshas has now evolved to wider areas of social issues such as gender equality and is now routinely used for education and outreach using humour and entertainment.

The video

The vesha that we are going to enjoy now (the video above), dissects a very common tradition in India, where the bride, after marriage, leaves her parents’ home and goes to live with her husband and his family. The author wonders what would happen if the situation was reversed and the husband had to leave his home and go stay with the bride’s family. The title of the skit “Banne ekaj ghar ma” translates to “Both of them in the same house” signifying that a marriage (at least in the Indian context) is not just a contract of two individuals but a union of two whole families. The story unfolds in the backdrop of a “raja” or a king’s court in session with the king listening to the complaints of his subjects and trying to frame laws to help them.

I have edited the bhavai into sections or scenes a) for brevity and b) so that I can pop in between to explain what is happening...and also...nobody wants to watch anything which is longer than 10-15 minutes tops!

This Bhavai starts with the entire cast on stage invoking the elephant god Ganesha, remover of obstacles. The narrators then welcome all the spectators (offering “salaam” or greetings) and introduce the title of the skit.

The first scene shows the king’s court in progress with one of his subjects sharing his grievance. His daughter, his only child is getting married and hence preparing to leave his house to go stay with the husband’s family. He laments that he would be left all alone as his wife is already deceased. The king proceeds to “solve” this problem by decreeing that from now on, all those who have a single girl child need not send their daughters away after marriage. Instead, in such a situation, it will be the groom who must give up his family and come stay with the girl’s family.

Moving along, in the next court session, the queen herself visits the king to tell him that the law he passed is totally useless, as usual. They themselves have only one son whose fiancée is also an only child and so according to the new law, the son would have to leave after marriage, leaving his kingdom heirless. To fix this, the king introduces an amendment to the law saying that in case of the bride and groom both being only children, the couple as well as both their families shall live in the same house, so that no one has to go anywhere...hence the title.

The last scene again has the narrators discussing this new amendment with the jester joking that one unexpected outcome of this amendment would be that parents who would not want to see their children leave after marriage, would be forced to “plan” their families (in other words, go for birth control measures) after having one kid, as only in that case would they be able to live with their children post marriage.

Changing traditions

Traditionally, the Bhavai troupes did not have any women...the female characters in the veshas were also performed by men, but in recent times, women have not only played roles in the skits but also directed and produced Bhavai performances. What started as rebellion against restrictive practices has itself had a sort of mini rebellion in its own evolution.

Such traditional forms of entertainment and socializing need to be revived and actively encouraged if we are to present an alternative to excessive information overload provided by the onslaught of technology and social media...maybe by making use of the same technology or social media to support such folk culture practices.

Thanks for watching!

Bhavai : Banne ekaj ghar ma (Both in the same house)

Clay art and storytelling

by Janki Shah

About Ganesha

The annual birthday celebration of the elephant-headed god Ganesha is one of the biggest festivals in the entire world. It is unknown when Ganesha Chaturthi was first observed but the festival has been publicly celebrated in Pune since the era of the great king Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the founder of the Maratha empire.

In 1893m Lok Manya tilak urged people to celebrate Ganesha Chaturthi to unite people during British rule.

The festival served as a community gathering in a time when the British discouraged social gatherings to avoid protest against British rule. Hence this festival is connected to Indian Independence and brings all the community together, today as well.

For these weeks and months, people buy or make statues of the god Ganesha. They have faith that paying homage to Ganesha will remove obstacles and bring success and good fortune in the coming year.

Traditionally, the idol was sculpted out of mud and on the last day the Ganesha idol returned to earth by immersing in a nearby body of water and returned back to nature.

Ganesha is the god of wisdom, prosperity, and good fortune.

The story

Here is the story of Lord Ganesha's birth and its elephant head.

There are three main characters:

- Lord Shiva, who is known as a destroyer and transformer

- His wife, Goddess Parvati, who symbolizes fertility, love, and devotion

- Their son, Lord Ganesha who is known as the god of wisdom.

Lord Shiva used to be busy meditating and stayed away from his wife and home. Goddess Parvati felt lonely at home, and felt insecure living alone. One day while she was taking a bath, she wished for a baby. From the dirt of her body, Lord Ganesha was born.

She stayed with her child and she was very happy.

One day, Goddess Parvati was bathing, and her son was guarding the door. Meanwhile, Lord Shiva came to meet Parvati. As per the commitment given to his mother, Lord Ganesha did not allow Shiva to enter. Lord Shiva also could not recognize his own son, and was very angry with the boy. With his Trishul, he cuts off his child's head. As soon as Parvati noticed her son is no more, she weeps and begs Shiva for her son's life.

Lord Shiva realized his mistake and sends his gans (followers) to search for another head from the forest. His followers bring the head of a baby elephant to Shiva, and he attaches the head to his son's body.

On Ganesha's rebirth, Lord Shiva declared his son head of all gans—meaning Ganpati.

Why the elephant?

If we think of everything logically, why didn’t Shiva attach Ganesha's original head instead of the elephant head?

Let's assume that the original head of Ganesh was damaged completely. Then, why didn’t they use any human head, instead of an elephant head?

Let's come to this conclusion: You may have heard before that Lord Ganesha's head symbolizes intelligence and wisdom:

- A big ear symbolizes a good listener.

- A small mouth symbolizes speaking less.

- A trunk symbolizes efficiency.

Also, there is a scientific reason behind this: The elephant's hippocampus is highly developed, and its cerebral context is also large. In fact, it has the same amount of neurons as humans—that is why the elephant is highly intelligent and a problem solver.

On this 73rd Independence Day, August 15, 2020, we feel proud to present India. The country shares many common values with our beloved country Canada, like inclusiveness, secularism, equality, humanity, and peacekeeping.

Wishing you all Happy Independence Day!

Indian dance

by Darshini Shah

Indian dances are traditionally classified into two categories: folk dances and classical dances. A third, modern category has been added, which is called Bollywood dance.

Classical dances

Classical dances are structured dances, with strict rules, years of training, and unique costumes and jewelry. It is performed to worship, to tell stories, to showcase achievements in the field of performing arts, and to celebrate culture and tradition. The music of each classical dance has its own specific style including musical instruments. The Sangeet Natak Akademi (the Indian national academy for performing arts) currently confers classical status on eight dance styles: Bharatanatyam (Tamil Nadu), Kathak (North, West and Central India), Kathakali (Kerala), Kuchipudi (Andhra), Odissi (Odisha), Manipuri (Manipur), Mohiniyattam (Kerala), and Sattriya (Assam).

Folk dances

Folk dances have fewer rules and require less training. They have specific costumes and jewelry and are generally done for celebrations and fun. There are innumerable folk dances in India. Some very popular ones are, Lavni from Maharashtra, Garba from Gujarat, Ghoomar from Rajasthan, and Bhangra from Punjab.

Bollywood dance

Bollywood dance is a very inclusive dance style. It fuses every dance style that the choreographer can think of and uses instruments from the whole world to create different effects.

Performing Bharatanatyam

There are three main classifications in Bharatanatyam. They are called Nritta, Nritya, and Natya.

Nritta means pure dance, a presentation of rhythm through graceful body movement.

Nritya consists of footwork, hand gestures, and expressions. It relates to Rasa and the psychological state. Angika abhinaya relates to Hasta (means hands), eyes, eyebrows, lips, etc.—these are very important in Nritya. It can be described as the explanatory aspect of dance where hand gestures and facial expressions convey the meaning of the song lyrics. Bhav (emotional expressions) of the dancer are of prime importance, so it can also be considered as the miming aspect of dance.

Natya is telling the story through dance and music or laya and abhinaya or Nritta and Nritya.

In the video above, Darshini Shah performs Nritta and Nritya styles of dances in this performance followed by a small tutorial for each.

The history

Indian classical dances are documented 2,600 years ago in the books called ‘Natyashastra’. This book is the ultimate resource for performing arts, as all the classical dances emerged from it. With the passing of time, all of the dance styles evolved and developed their own distinct techniques. But all classic dances shared a few things in common: dances were communicative and used mainly to worship.

The history of dance had two turning points. In the 14th century, during the Moghal empire, the North Indian dance and music fused with middle eastern styles. The costumes, jewelry, musical instruments, lyrics, and techniques of dance moves all changed. The biggest at that time was when dance traveled to Moghal courtrooms from temples.

The second turning point happened during British rule to every classical dance. As mentioned, the dances are very communicative; the British government banned the practice of classical dances among the general public to avoid any conspiracy against the British government. Dances were only allowed to be performed for the entertainment of diplomats, rulers, and wealthy people. When India became independent, all these dances were liberated, which we are now celebrating!

Some passionate people worked really hard to revive and reestablish Indian dances in society. One of them was Rukmini Arundale. She learned Russian ballet from Anna Pavlova and Indian Bharatanatyam from Pandanallur Minakshi Pillai. We can also celebrate the cultural collaboration that India has shared globally.

Indian textiles and clothing

by Darshini Shah

India’s textile sector is one of the oldest industries in the Indian economy, dating back several centuries.

The industry is extremely varied, from hand-spun and hand-woven textiles to sophisticated mills. The power looms/hosiery and knitting sector form the largest elements in the textile sector. The close linkage of the textiles industry to agriculture (for raw materials such as cotton) and the ancient culture and traditions of the country in terms of textiles makes it unique in comparison to other industries in the country. India’s textile industry can produce a wide variety of products suitable for different markets, both within India and across the world. The material includes cotton, rayon, nylon, silk, wool, satin, viscose, jute, muslin, hosiery, flannel, fleece, and many more.

Textile and clothing are interwoven in Indian culture, and part of every occasion. Different parts of India have different dress codes that vary in material, colours, designs, and patterns. By looking at the dress, we can guess the region, language, culture, ethnicity, caste, class, and language spoken by that person. We can also guess the occasion for which it is going to be worn.

Weddings

Click to view the gallery below and learn more about different styles and customs.

Textiles

The textile heritage of India is rich, with over 120 weaves, over 40 hand embroideries that have been in practiced for centuries, and innumerable styles of ancient, traditional and modern clothes.

Click to view the gallery below and see some examples of embroidery.

Some of the embroideries have been in existence in India from the time of the Rigveda, the most ancient scripture of India.

With the effect of globalization, costumes have even evolved from being worn on occasions, to also in day-to-day life, according to trend, usability, and availability.

While India has such great variety in traditional wear, there are some similarities, like covering the head. Women cover their heads with pallu/ghunght while men at most places cover their heads with turbans or hats.

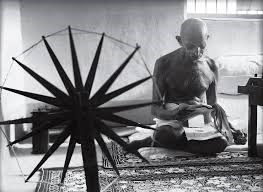

Khadi movement

On one hand, India has shining, rich, colourful traditional textiles, on the other hand, it holds a strong history of Khadi. The khadi movement by Gandhi was aimed at boycotting foreign cloth.

Shared from Wikipedia: "Mahatma Gandhi began promoting the spinning of khadi for rural self-employment and self-reliance (instead of using cloth manufactured industrially in Britain) in the 1920s in India, thus making khadi an integral part and an icon of the Swadeshi movement. Khadi is a hand-woven natural fiber cloth originating from eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, mainly Eastern India, Northeastern India, and Bangladesh, but are now broadly used in Pakistan and throughout India. The cloth is usually woven from cotton and may also include silk or wool, which are all spun into yarn on a spinning wheel called a charkha. It is a versatile fabric, cool in summer and warm in winter. In order to improve the look, khādī/khaddar is sometimes starched to give it a stiffer feel. It is widely accepted in fashion circles."

"The way we dress is destroying the world. Textile has become the third-largest polluter in the planet," says Sadguru. By the use of Khadi, we can conquer the war against pollution through the polymer fibers used for modern textiles.

Overall, the textile industry does have an impact not only on fashion and economy, but is greatly connected with lifestyle, tradition, beliefs, and faith. I feel honoured to be part of the celebration of Indian Independence Month through the lens of Atlantic spinners and I am happy to share the prosperous history of Indian Textile and clothing.

Add a comment to: Indian Independence Month: A Virtual Celebration