Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window

You take a tour of the Halifax Citadel, attend a service at St. Mary’s Cathedral, and watch the fireworks at Grand Parade—but what do these places have in common?

All of these Halifax landmarks, and many more, were constructed with locally sourced stone—and with good cause! People don’t talk about the rocky shores of Nova Scotia for nothing. Let’s take a look at two of the first quarries founded near Halifax, and what they helped to build.

Like a rolling stone

Though many types of stone were quarried in and around the city, this article will focus on three main types: bluestone, granite, and ironstone.

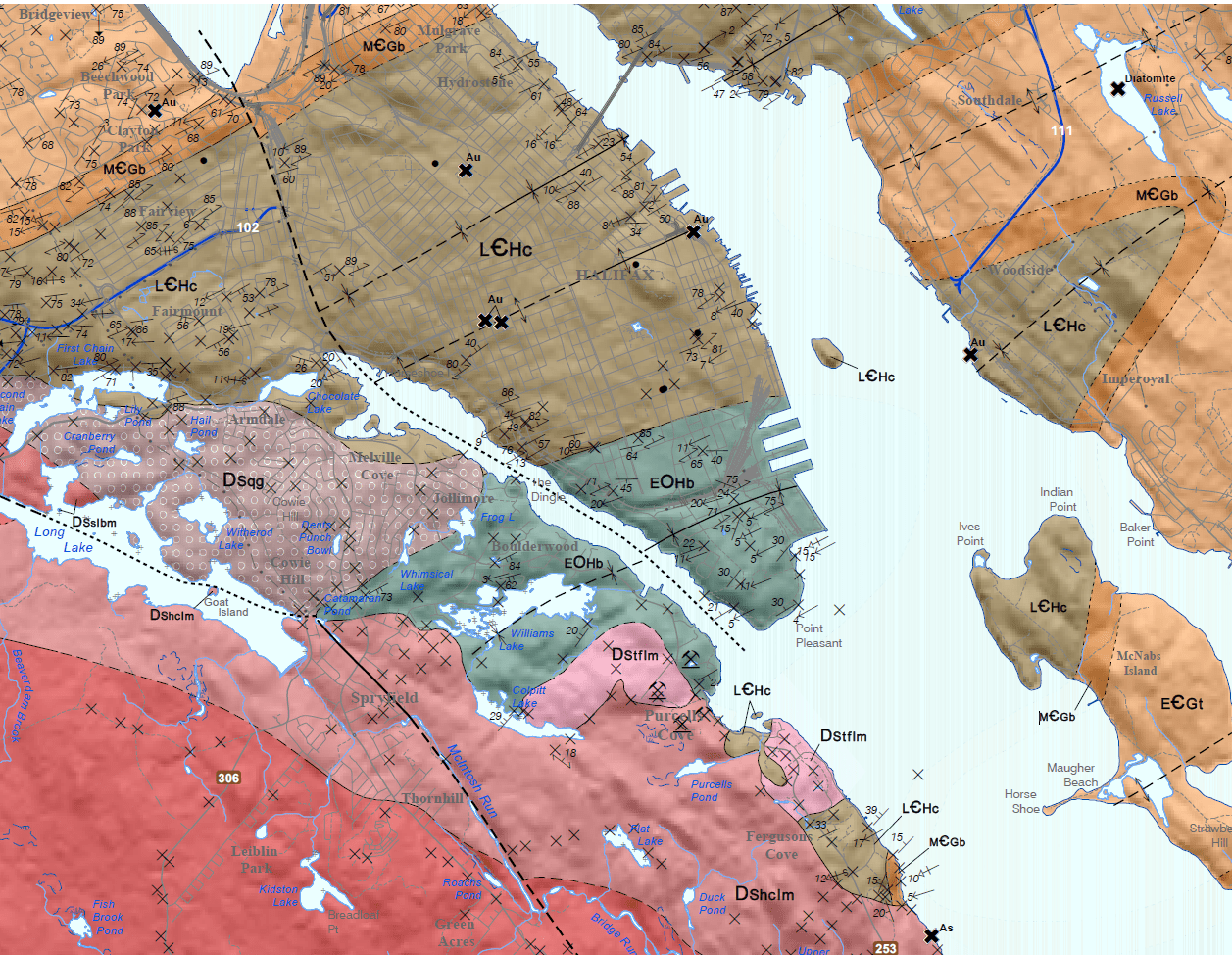

Bluestone (teal area of the above map), also known as slate, is made of alternating layers of silt and sand that were once found at the bottom of the ocean nearly 500 million years ago.

Granite (coral pink area of the above map) is a type of igneous rock—meaning it was formed when magma (molten rock) became cold and crystallized—forming a solid stone. Granite often includes flecks of shiny minerals like quartz, black mica, and feldspar.

Ironstone (teal and light brown areas of the above map) is a type of sedimentary rock. These rocks were originally formed near the earth’s surface, but when erosion and weather effects covered the stone particles in mud and sediment, they were reformed into something new. Ironstone lives up to its name, typically containing at least 15% iron in its composition.

King and Queen's quarry

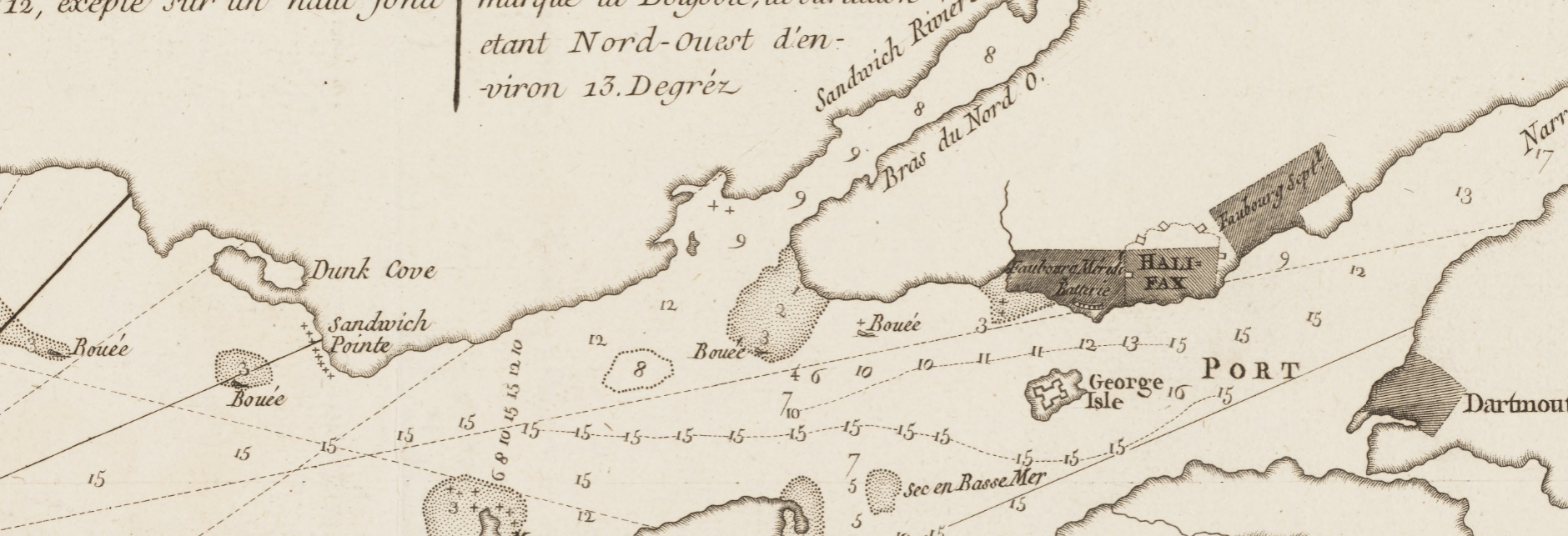

In 1749, when Halifax was first founded by the British, the outer area of the city was divided by the government into lots for settlement. This division included “Quarry Lots” on the far side of the Northwest Arm.

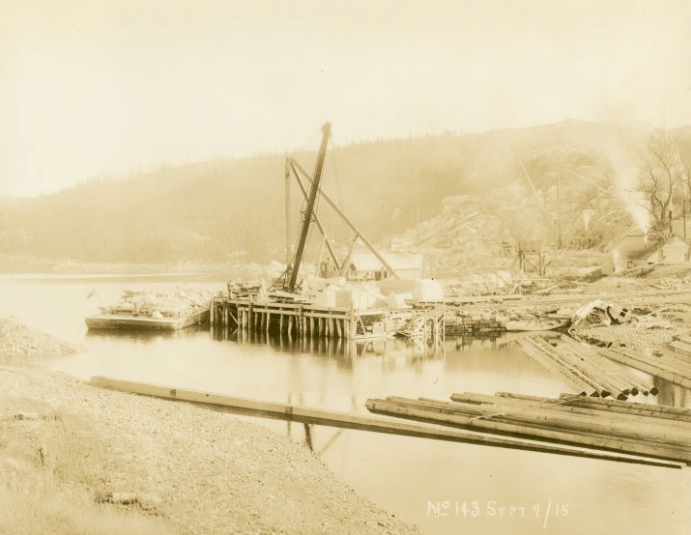

The King’s Quarry was located in Purcell’s Cove off of what is now Bluestone Road. The quarry was approximately 150 metres across, and was made up of two horseshoe-shaped excavations. The site was very close to the water, which made transporting the harvested stone to other areas of the city by boat a relatively easy task. At its peak, the King’s Quarry employed around 160 men and produced up to 100 tonnes of stone a day. This quarry continued to be active well into the 20th century.

As the road’s name indicates, the King’s Quarry was especially known for its bluestone, but ironstone was also regularly quarried here. The rock collected here was used in the construction of a number of significant buildings in Halifax, including parts of the Halifax Citadel, the Pickford and Black building currently located at 1869 Upper Water Street, and Dalhousie University.

In fact, so much of the stone from this quarry was used in the construction of Dalhousie, that in later years the site was referred to as the Dalhousie Quarry.

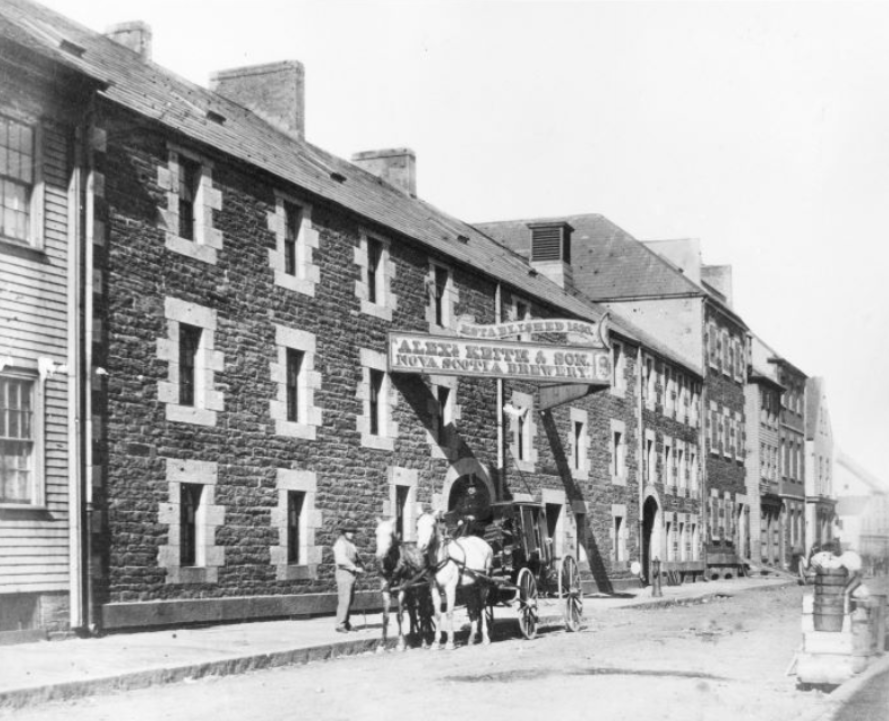

Ironstone was more rugged-looking than some of its counterparts. As a result, it was often paired with other types of rock in order to improve its appearance. Granite and sandstone were often used as accents to “pretty” it up. This can be seen on several buildings around Halifax, including the Morse’s Tea building at 1877 Hollis Street, and Alexander Keith’s Brewery at 1496 Lower Water Street.

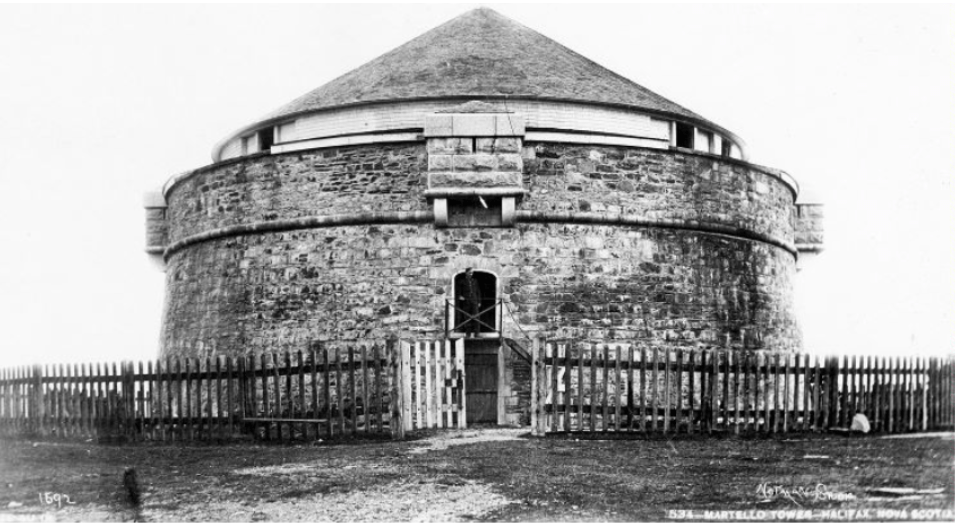

In the late 1700s/early 1800s, John Trider, a government contractor, was granted a 200 acre Quarry Lot also in the Purcell’s Cove area. This property was rich in granite and ironstone. Trider’s stone was used in the construction of The Prince of Wales Martello Tower in Point Pleasant Park in the 1790s, as well as the Sherbrooke Tower on McNab’s Island in 1815.

The rock in this quarry was of such high quality that the land was assumed by the government in 1828 for the purposes of the Royal Engineers. The property was officially deeded to three men: Gustavus Nicolls, a Colonel in the British army and Commander of the Royal Engineers, Charles Morris, the Surveyor-General, and Sir Rupert de George, Secretary of the Province of Nova Scotia. From that point forward, it was known as the Queen’s Quarry.

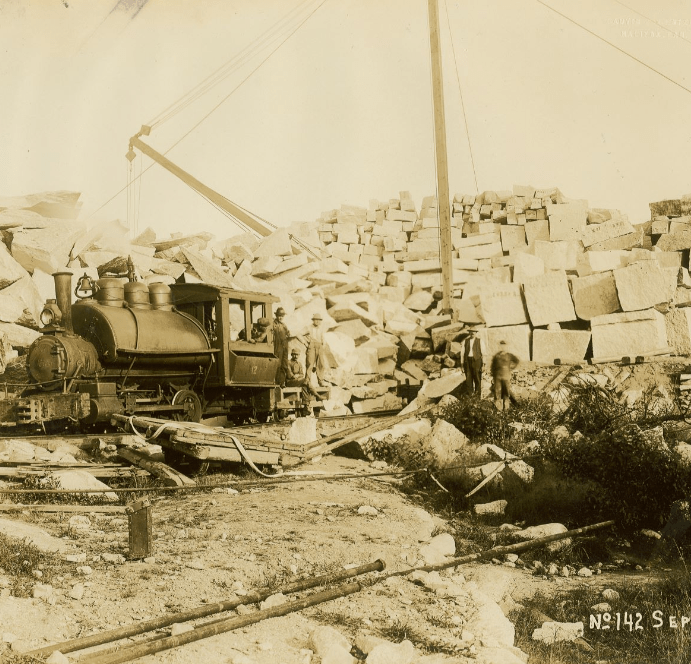

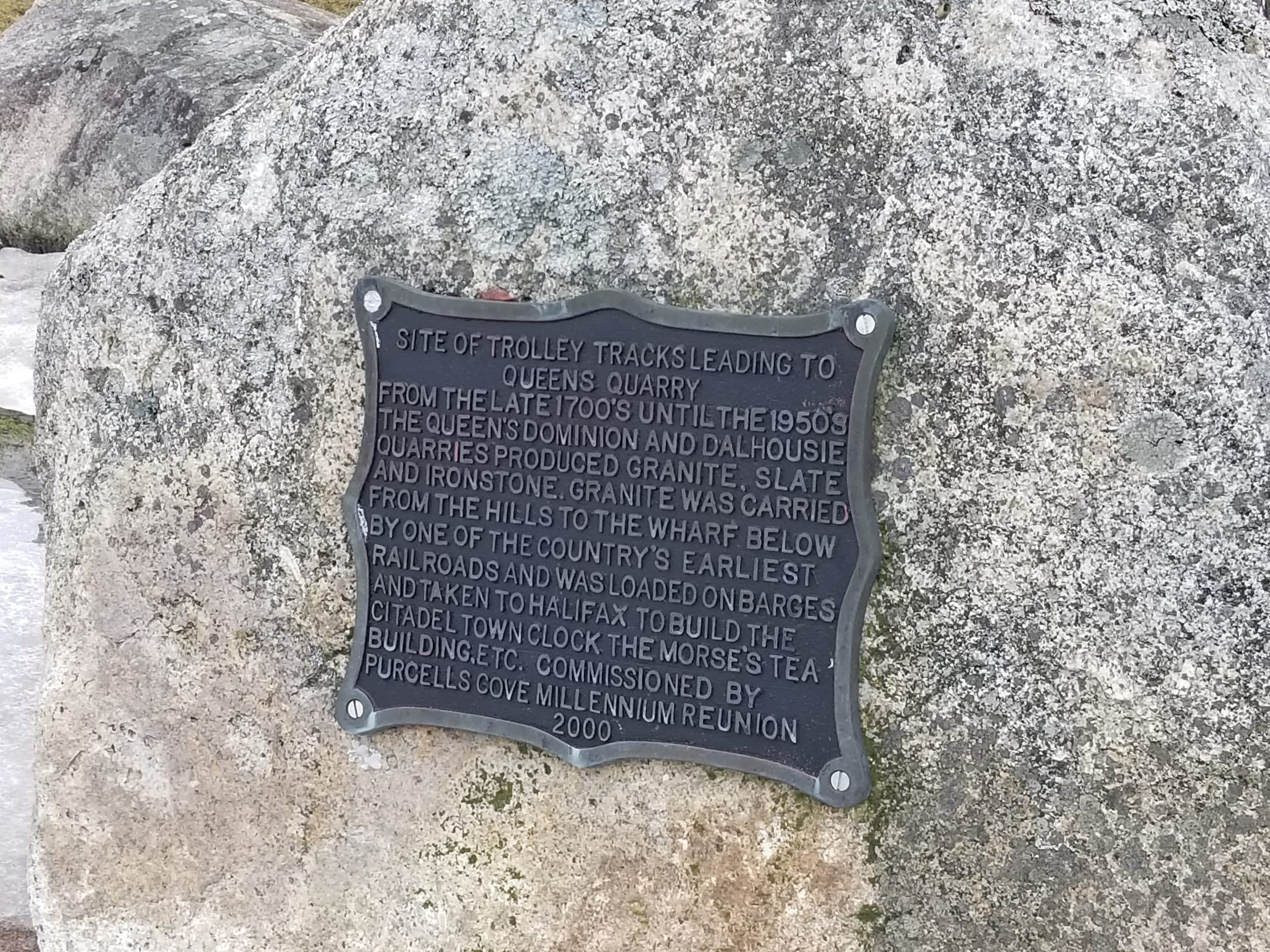

What makes the Queen’s Quarry especially unique was its rail system. The Queen’s Quarry was located at the top of a large hill off of the main road, 60 metres above sea level, behind the current Purcell’s Cove Social Club. This made moving the large granite rocks from the quarry to the barges at the wharf below a tedious task. In 1834, a 400-metre railway track was installed to help make transportation of the stone more efficient. This steam railroad is said to be the oldest industrial railway in Atlantic Canada. A monument at the Purcell’s Cove Social Club stands as a marker for the old railway track.

In addition to those mentioned above, granite from the Queen’s Quarry was also used in the construction of many other Halifax landmarks, including the Halifax Citadel, York Redoubt, Fort Charlotte on George’s Island, Saint Mary’s Basilica, and Rockhead Prison. When the Queen’s Quarry ceased production, mining operations moved to the Coughlan Quarry, also in Purcell’s Cove.

Looking forward

Halifax is an ever-growing city. There is always something being built, a new architectural endeavour being constructed. Our new buildings are complex and creative, and they demonstrate what modern designs and materials are truly capable of. However, there is beauty in our built heritage, and satisfaction in knowing which materials used were harvested from our own backyard. These stones tell a magnificent story that connects the earth we stand on to the places we know and love.

Learn more

Want to learn the difference between Purcell’s Cove granite and Terrance Bay granite? Want to know why you shouldn’t use sandstone as a foundation? Or where you can find Scottish red granite on Spring Garden Road? Check out this video with Howard V. Donohoe Jr., Ph.D. P.Geo from the Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia:

Library resources

“Purcell’s Cove” by Elsie (Purcell) Millington, 2000, Ref 971.6225 M655p, opens a new window

Online resources

Backlands Coalition:

Historical importance of the Purcell’s Cove Quarries, opens a new window

Canadian Encyclopedia:

Geography of Nova Scotia, opens a new window

Dalhousie University:

Purcell's Cove Granite Quarries Thesis, opens a new window

DAL ROCKS! Thesis, opens a new window

Interpretation Planning Thesis, opens a new window

Encyclopedia Britannica:

Iron-rich sedimentary rocks, opens a new window

Intrusive Rock, opens a new window

Facebook – Mining Association of Nova Scotia:

King Quarry in Purcell's Cove is likely the oldest quarry in Halifax., opens a new window

Google Books:

Report on the Building and Ornamental Stones of Canada, Volume 2, opens a new window

Google Maps:

Government of Nova Scotia:

OFM ME 2014-010: Bedrock Geology Map of the Halifax Area, Nova Scotia [1:50 000], opens a new window

Halifax Bloggers:

Halifax Military Heritage Preservation Society:

PURCELL'S COVE QUARRIES, opens a new window

Harvard University:

Harvard University, Harvard Map Collection, G3422_H3_1778_M6_3633447023, opens a new window

Historic Places:

Keith Hall and Brewery, opens a new window

National Geographic:

Igneous Rocks, opens a new window.

Not Your Grandfather’s Mining Industry:

Nova Scotia Archives:

https://archives.novascotia.ca/halifax/archives/?ID=21

https://archives.novascotia.ca/meninmines/archives/?ID=486

https://archives.novascotia.ca/meninmines/archives/?ID=487

https://archives.novascotia.ca/notman/archives/?ID=818

https://archives.novascotia.ca/photocollection/archives/?ID=6990

https://archives.novascotia.ca/rogers/archives/?ID=90

https://archives.novascotia.ca/meninmines/history/quarries/

Science Direct:

Seniors College Association of Nova Scotia:

Add a comment to: Imperial Halifax – A City of Stone: A Brief and Not At All Definitive History