During the Nazi reign in Germany, Lebensunwertes Leben - or, roughly translated, "life not worth living" - was a term applied to all people who did not fit the mold of Hitler's ideal Aryan race: the physically and mentally disabled, the LGBTQ community, Romany, the genetically and racially "inferior." Jewish people were especially targeted by the Hitler and the Nazis. They were used as a scapegoat for nearly all of Germany's problems following the First World War. And, as Hitler's power in Europe grew, he used it to do the unthinkable.

World War II: The Holocaust

Hitler's hatred of the Jewish people was never a secret. When he came to power he boycotted Jewish owned business, removed Jewish people from jobs in the civil service, and limited Jewish enrollment in German schools. As time went on, he stripped Jewish people of their property and destroyed hundreds of synagogues.

To the Nazis it did not matter whether a person actually participated in the Jewish faith; it was about a person's heritage and Hitler wanted that ancestry erased.

In 1933, Poland had the largest Jewish population in Europe totaling around three million people. Because of this, Poland became the first target for Hitler in his plan for domination. Once the country was under his control, the Nazis gathered Polish Jews into ghettos - enclosed areas of the city where no one was allowed in or out. Inside the ghettos, conditions were disastrous ans many people died of starvation and disease.

Jewish people were also taken from their homes and sent to concentration camps as slave labourers. Here they were held captive and forced to work. If an inmate refused to work, they were not fed. Many people in these labour camps died, either from starvation or exhaustion. The Nazis took additional advantage of the prisoners in their concentration camps by using them for medical experimentation. However, Hitler and his highest ranking officials decided that segregating, enslaving, and torturing the Jewish population was not achieving their goals. They developed what they called their "Final Solution" - to fully exterminate the Jewish population.

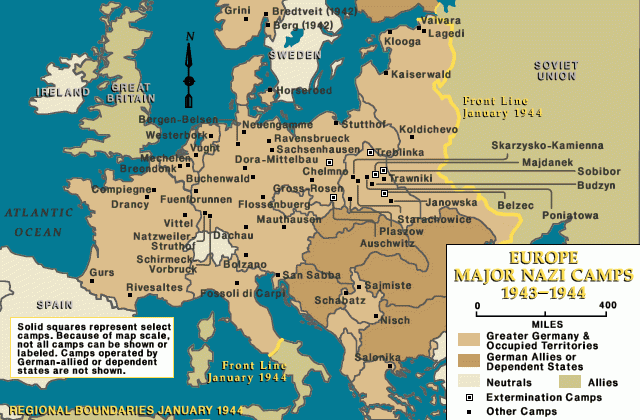

In 1941, the Nazis opened their first killing centre.

Chelmno was located in central Poland. The camp consisted of a large manor house, which housed the administration of the camp, and a large section of forest. The first victims at Chelmno were Jewish residence of the nearby village. They were brought in trucks to the camp by Nazi officers. Upon arrival, any valuables they had in their possession were handed over to the camp administration. The prisoners were led to the cellar of the house and loaded into another van fifty to seventy people at a time. When it was full, the van was sealed shut, the engine turned on, and carbon monoxide gas was pumped into the van asphyxiating the people inside. When the air had cleared, the officers simply drove the van into the forest, and disposed of the bodies in mass graves.

Other killing centres followed. Between 1941-1943, the Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz-Birkenau killing centres were constructed. Many prisoners were killed immediately upon their arrival in these camps. Those who were not murdered were put to work, starved, and tortured until they could take no more.

Although Allied intelligence reportedly knew about the Jewish mass murders as early as June 1941, the first public report of the killings was not made until February, 1942 in the Polish Home Army paper Biuletyn Informacyjny. As more and more information was made public one thing was perfectly clear - Hitler had to be stopped.

Sergeant Morton Ralph Heinish (1921-1941) - R76013

Morton Ralph Heinish was born July 28, 1921 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His parents, Noa and Rachel (Spiro), were Jewish immigrants from Romania and Poland respectively. Using available resources it is unclear exactly when Noa and Rachel came to Nova Scotia, however, we do know that they were married in New Glasgow in October, 1917. began a clothing business called Rafuse & Heinish, clothiers and furnishings, with business partner Elkanah Rafuse around 1917. The shop was located on the east side of Barrington Street near where the Barrington Hotel stands today. While Noa ran the store, Rachel managed the household which also included Morton's older sister Anna Ruth. The family lived at 110 Preston Street (now 1788 Preston Street). When Morton was about ten years old, his mother became ill. She was diagnosed with uterine cancer and passed away in April of 1933. The following year his father remarried Sarah (Saffron) from Springhill, Nova Scotia; her ancestral roots were also from Poland.

Morton attended Quinpool Road School, the Morris Street School, and the Halifax Hebrew School. He attended high school at the Halifax Academy, now 1649 Brunswick Street (a part of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Campus). Morton liked to swim, play baseball and softball, and skate. He spent many years in the Boy Scouts, and was a member of the Halifax Young Judaea and the Aleph Zadik Aleph, or AZA. When he reached adulthood, he stood five foot six inches tall, had a fair complexion, blonde hair, and blue eyes. Though he occasionally used glasses for reading, Morton had keen eyesight. In fact, when given an eye test it was discovered he could see more sharply than the average person at a distance of twenty feet.

For Morton, World War II must have felt like a particularly personal battle. He was Jewish, after all; his parents had only moved from Poland and Romania to Canada some two decades prior. If they had remained in Europe, what would have become of them? Would they be fearing for their lives, or would they have already lost them? Even though he did not yet know the extent of the horrors his people were facing, it is not hard to imagine that Morton felt that he could not sit idly by.

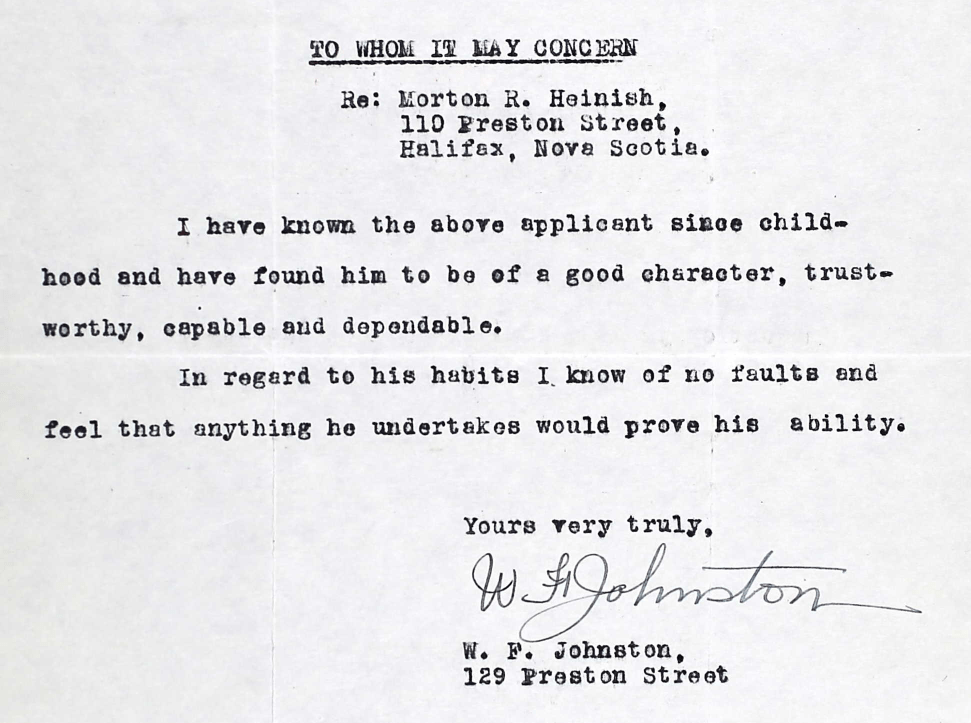

Morton was 19 years when he entered the local Halifax recruitment office in October of 1940. His overall good health coupled with his glowing recommendation letters made him an excellent candidate for service. Within a few days he was sent by train to Toronto to the No. 1 Manning Depot of the Royal Air Force (RAF) to begin his training in the Special Reserve. He was given the introductory rank of Leading Aircraftman (LAC).

There were many roles to fill in the RAF both on the ground and in the air. In the early 1940's even operating a fighter plane was a two person job. Planes required an air gunner who handled the artillery and radio communications, and an observer, or navigator, who also acted as the aimer for bombs when required. Perhaps in part thanks to his keen eyesight, Morton was selected to train as a observer. He began flying school in November of 1940 and his observer-specific training in early 1941.

However, Morton didn't take to the role as much as the RAF had hoped he would. Morton struggled in his initial courses, so much so that his Flight Lieutenant recommended he be grounded to work in a trade, or be discharged from the RAF all together. In the spring of 1941, Morton was remustered, or reassigned, to be a gunner with the rank of Sub-Lieutenant.

Morton continued his training in the RAF. His new position as gunner seemed to suit him better. In the summer of 1941, he was promoted Temporary Sergeant and in October Morton was sent from his training facility in Canada to the 25th Operational Training unit in Finningley, UK. After about a month of additional training he was then sent to Coningsby, UK to join the 97th Squadron of the RAF.

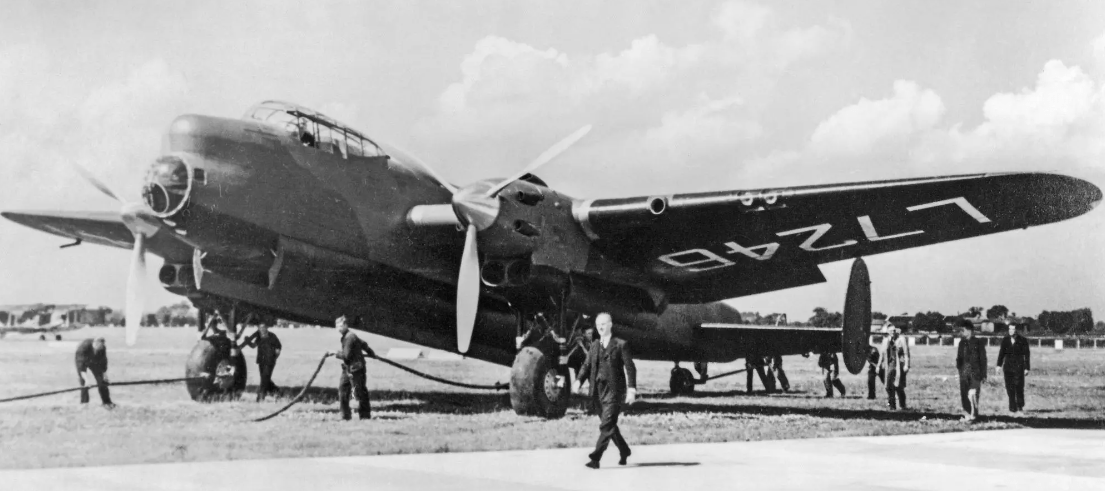

The 97th Squadron of the RAF, also known as the "Straits Settlements" started as a training squad at the beginning of the war, but by 1941 they were making their first bombing missions over mainland Europe. Their motto was "Achieve Your Aim." When Morton was assigned to the squad, the 97th were frequently flying the Avro 679 Manchester (A679M). The A679M was a twin engine medium bomber designed by A. V. Roe & Company. The plane featured a 1,760 horsepower, 24-cylinder Rolls-Royce Vulture I engine with a maximum speed of approximately 426km/hour. It could hold a crew of seven, had two 0.303 inch machine guns in the front of the plane, and could carry bombs up to 10,350 pounds. The interior of a A679M plane would be the last place Morton would be seen alive.

On the morning of December 18, 1941, Morton and the crew of the A679M, began a bombing mission over the city of Brest, near the western tip of France. To the Nazis, Brest was considered an important city to have under their power; its harbour gave easy access to the Atlantic ocean, which put them in very close proximity to Britain both by air and by sea. As Morton and the crew of the A679M approached Brest, they were attacked by enemy aircraft. A German Messerschmitt BF 109 fighter plane shot them down, and the A679M crashed into the ocean seven kilometres outside of the city.

At first, it was unclear exactly what had happened to Morton and the rest of the crew. Witnesses of the crash saw several passengers bailed out of the plane before it hit the water; it was unclear at that time if Morton was among them. A letter was sent to Morton's father Noa informing him that his son had failed to return from the mission, but admitted they did not know what had become of him. In time it was discovered that Morton's crewmates Sergeants Isaac Hewitt, Gwynne Pryce Thomas, and Thomas Michael Wade survived the crash, but were captured as prisoners of war. By January, 1942, with no sign of the other men the worst was concluded: Petty Officer Neville George Stokes, and Sergeants John Robert Conn, George Gardiner Fell, and Morton Ralph Heinish were declared dead.

Noa was notified of Morton's death by letter.

In 1946, a few months after the war was over, Noa received an additional letter. This one contained something very precious: Morton's Operational Wings. The letter, signed by T. K. McDougall, RCAF Records Officer, stated: "I realize there is little which may be said or done to lessen your sorrow, but it is my hope that these "Wings", indicative of operations against the enemy, will be a treasured momento of a young life offered on the altar of freedom in defence of his Home and Country." Though the wings were no doubt a cherished item in the Heinish household, it is hard to say if they brought them any particular comfort.

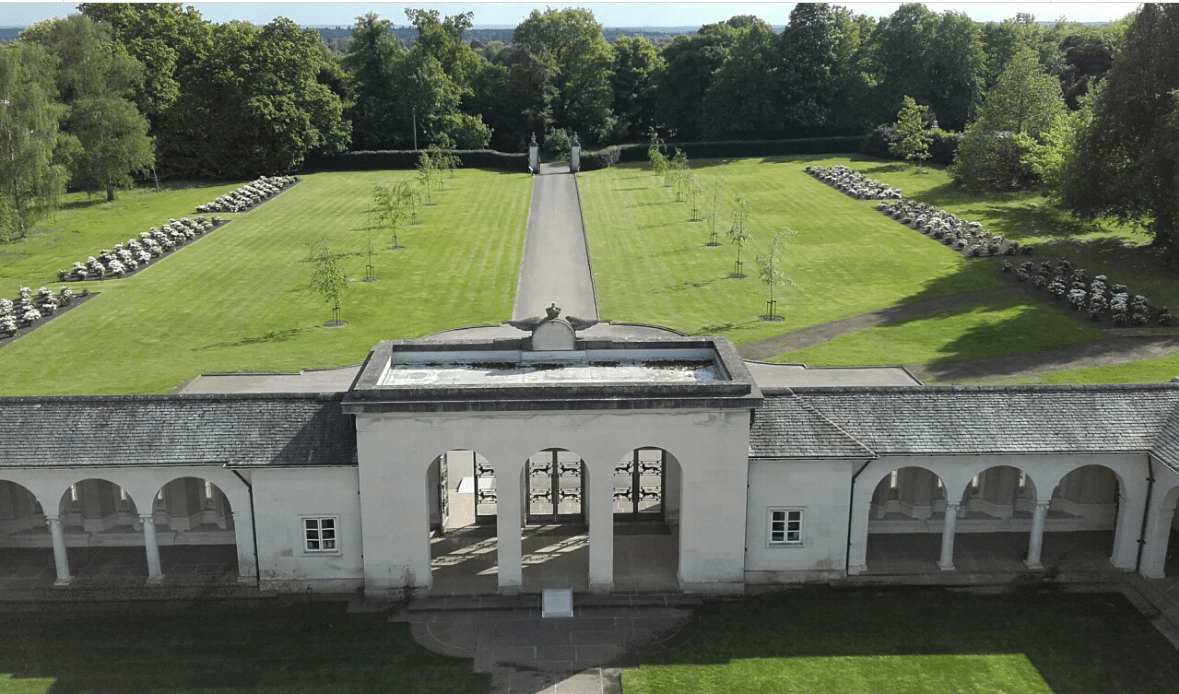

In lieu of a gravesite, Morton was honoured at the Runnymede Memorial in Surrey, UK. He is memorialized alongside more than 20,000 other men and women of the RAF for lost their lives in World War II and have no known gravesite. The site was designed by Sir Edward Maufe and officially unveiled by the Queen in the autumn of 1953.

The Finishing Lines

As the war continued, the Allied troops were eventually able to push the Nazi armies back. The concentration and killing camps were liberated and those who had spent so long suffering under Nazi cruelty were finally freed. In April 1945, knowing he was losing the war, Hitler committed suicide. On May 5, 1945, Germany admitted defeat. The war officially ended on September 2, 1945 when Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers.

As incredible as these victories were, and as worthy of celebration and commemoration as they still are, they little solace to those who lost their lives and to their families who were left to grieve.

By the end of Hitler's reign, approximately 6 million Jewish people were murdered. In addition, an estimated 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war, 1.8 million Non-Jewish Polish citizens, 250,000 Romani, and 250,000 disabled people lost their lives under Nazi tyranny. Millions of soldiers and civilians died on the battlefield or in the crossfire. Canada alone suffered 45,400 military deaths, with Morton Ralph Heinish among them.

Morton would not live long enough to know the true horrors suffered by his people during Hitler's "Final Solution." But to those who survived and to those who live today thanks to the sacrifices made by Morton and others like him - we have to know. And never, ever, forget.

Library Sources

Other Sources

Auschwitz - Photograph, United States Holocaust War Memorial Museum

Avro 679 Manchester, Bae Systems

Crash of an Avro 679 Manchester I off Brest: 4 Killed, Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives

Canada and the War, VE Day 8 May 1945, Canadian War Museum

Chelmno, Manor House Photo, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Chelmno, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

City of Halifax Civic Address Conversion, Halifax Municipal Archives

Concentration Camp, Britannica

Concentration Camps, 1942-1945, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Einsatzgruppen: An Overview, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Forced Labor: An Overview, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Forced Labor in a Quarry, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Forgotten Fights: Assault on Brest, August - September 1944, The National WWI Museum, New Orleans

Germany in World War II, Florida Atlantic University Libraries

Heinish, Morton Ralph, Find a Grave

Heinish, Morton Ralph, Sergeant, Government of Canada

The Holocaust, The National WWII Museum, New Orleans

How many people did the Nazis murder? Holocaust Encyclopedia

Jewish Population of Europe in 1933, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Nazi Camps, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Nazi Medical Experiments, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

No. 97 Squadron, Virtual War Memorial, Australia

No. 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron Royal Air Force, The Wartime Memories Project

Nova Scotia Births, Marriages, and Deaths, Nova Scotia Archives

Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II, The National WWII Museum, New Orleans

Runnymede Memorial, Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Second World War Information Package, Library and Archives Canada

The Shocking Liberation of Auschwitz: Soviets "Knew Nothing" as They Approached, History.com

Auction: 18002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals, Spink

Waddington AFB, Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives

When did the world find out about the Holocaust?, Jewish Virtual Library

Who's Who in an RAF Bomber Crew?, Imperial War Museum

Add a comment to: Gone But Not Forgotten – Part 4: Sergeant Morton Ralph Heinish and the Second World War