During World War I, people across Canada and the world were mobilized to fight together for a greater good. They were willing to stand up for what they believed in even if that meant paying the ultimate price. But some people paid a price they did not expect.

To return home uninjured - well, that was a miracle! To return home scarred, or wounded - that was a badge of honour. But to return home only appearing to be healthy - that was complicated.

Sister Nurse Florence Louisa MacInnes

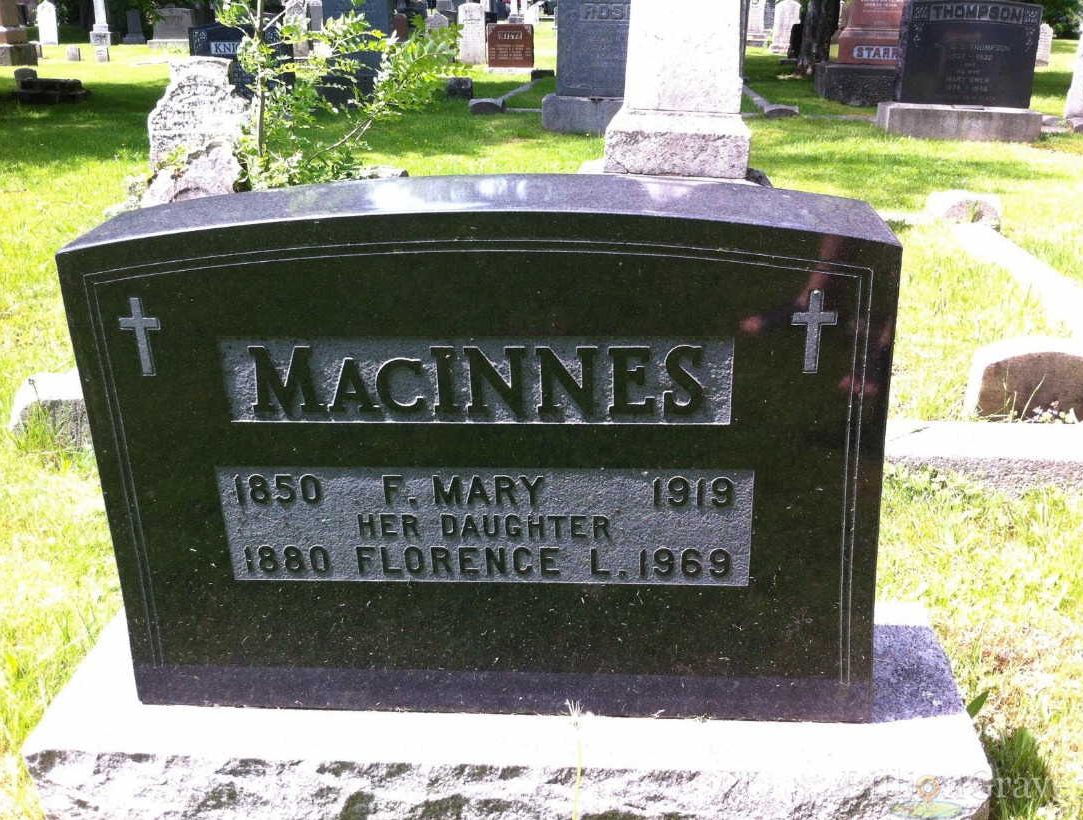

Florence Louisa MacIness (McIness, McInis, etc.) was born February 22, 1881 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Her parents, Henry and Frances (Gladwin) were both originally from Pugwash, Nova Scotia. They were wed in Halifax on December 18, 1873, and soon began their family. Their first child Henrieta was born around 1874, followed by Charles (born1876), then Florence, Nellie (born 1883), and their youngest child was Henry (born 1885). Florence's father worked as a machinist/engineer for the Intercontinental Railway, while her mother managed the household. The family lived in a number of locations throughout Halifax including Duffus Street, Campbell Road (now Barrington Street), Russell Street, and North Street.

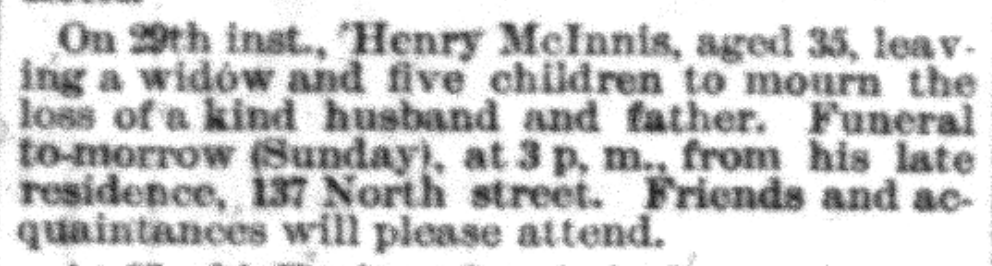

It was while living in their home at 137 North Street that tragedy struck the family. Florence's father passed away on October 30, 1886 when Florence was just five years old. While Henry's cause of death is unknown, there is no doubt that this would have been a terrible loss for the family. Exactly how Florence's mother was able to financially support the family is another mystery - perhaps they were able to subsist on a pension that Henry had left behind. In subsequent years, after Henrieta married salesman Roderick Morrison, the family's situation became a bit more stable. They all moved in together at 40 Coburg Road.

As a child, Florence suffered from several bouts of ill health. She had measles, scarlet fever, and mumps at a young age, any one of which could have been fatal. She also had appendicitis, which required her appendix to be removed. At one point she also suffered from a gastric ulcer. However none of these afflictions stopped her from growing into a strong woman. Florence put this strength towards helping others and attended the Victoria General Hospital (VG) School of Nursing.

The VG opened in 1887 as a renovation to the pre-existing Provincial and City Hospital. It was a massive improvement from previous hospitals in Halifax, but as a result it required a lot more trained staff. The solution was to not only operate the VG as a public hospital, but to also use it as a training facility for future nurses. In 1890, the first students attended the VG School of Nursing.

It was difficult to gain acceptance to the school. The requirements were: a grade ten education with strong marks, character references, and a submission of their birth certificate, as well as their health and dental records. Once accepted into the school the work was not for the feeble hearted. The students worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week, with only a few hours off on Sunday to attend church. The students were required to attend lectures, write exams, and were sent to Boston or Montreal for maternity nursing training. Despite the incredibly hard work, Florence graduated from the VG School of Nursing in 1909, and became the Night Supervisor at the VG, and later the Assistant Superintendent of Nurses.

Nursing at the VG was a difficult job: nurses cared for up to fifty patients at a time, wrote detailed reports, and performed more mundane chores including maintaining the heat, filling kerosene lamps, cleaning chimneys, washing windows, sweeping, and mopping. The job was hard and the hours were long, but Florence was up to the task.

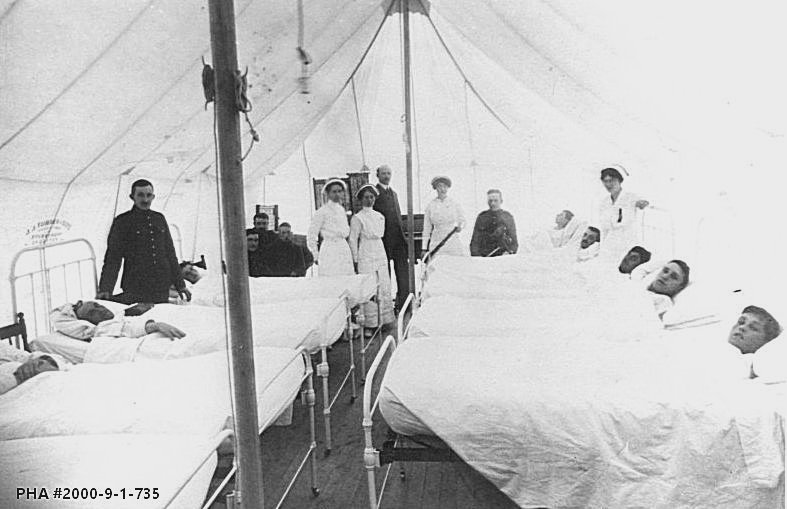

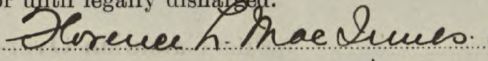

By 1914, Halifax was a-bustle with wartime activity. Men were heading overseas to fight Austro-Hungary, Germany, and their allies. Florence no doubt watched her friends, family, neighbours and acquaintances do their part to support the war effort. Before long, she decided she needed to do the same. Florence initially worked at the Military Hospital in Halifax, but it didn't take long for her to decide that working on the home front wasn't enough. On May 12, 1915 Florence signed up for the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) as one of Canada's Nursing Sisters. Sister Nurses had been working in one form or another for the Canadian military since 1885, but it wasn't until 1899 that they were considered an official part of the Canadian Army Medical Department. Members of the Nursing Sisters were granted the relative rank and pay (about $2 a day) of an army lieutenant.

In her service file, Florence is described as fair skinned with auburn hair and blue eyes, and stood a petite five foot four inches tall. She had a vaccination mark on her right arm, a light brown spot on her leg, and of course, a rather noticeable scar from her appendix removal on her abdomen. She was sent to England that same month and France shortly after to serve with the No. 1 Canadian General Hospital (No.1 CGN). While in France, she served at several military hospitals, including those found at Rouen and Etaples. Florence was nothing if not a dedicated nurse. In her file it is stated that she "worked very hard without a day of leave", that is, until her health took a turn.

In late November 1916, there was an air raid over Etaples. Following the raid, Florence began experiencing dizzy spells. These episodes were so debilitating that at one point she was unable to leave her bed for six weeks. She also developed experience extreme nervousness and an inability to sleep. On nights when she was able to fall asleep, her rest was disrupted by "distressing" dreams. Her memory became poor and she struggled to concentrate and focus on her work. She also suffered from depression, bouts of vertigo, severe headaches, and facial numbness. Over time she developed a tremor and had difficulty keeping her balance. On top of all of that, she was experiencing her menstrual cycle every week. Her medical file states: "She [Florence] thought at times that she was becoming insane."

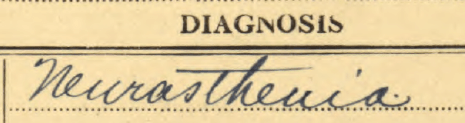

By the end of 1916, her health - both mental and physical - had deteriorated so much she was sent back to England for treatment. She stayed at a convalescent home in London for five weeks, followed by treatment at Ramsgate for an additional four months. By May of 1917, it was determined that her condition was so poor that she should not stay in England. Her file states: "This NS [Nursing Sister] should be invalidated to Canada at earliest possible date under medical supervision." In June she was sent back to Canada aboard the ship Letitia. Though she made some progress during her recovery time, her symptoms persisted and in some cases worsened. For example, doctors noted she was losing a notable amount of weight. So what was the diagnosis? Though a number of terms related to Florence's symptoms appear in her file, the diagnosis that appears more than any other is "neurasthenia," more commonly known as shell shock.

For wartime doctors, shell shock was initially only considered to be a physical condition. It was believed that soldiers who had been in the trenches and barraged by artillery fire had been concussed by the shock waves of the assaults. This resulted in expected symptoms: trembling, headache, dizziness, poor concentration and memory, and an inability to sleep. However, as the war progressed members of the military who had been nowhere near the front lines were experiencing these same symptoms. The idea of shell shock then began to include a mental component as well - that the stress of all things related to war could cause a victim to suffer a "weakness of the nerves". More accurately, the victims suffered a nervous breakdown.

Florence's file stated that her neurasthenia was caused by being overworked. The truth, of course, is that like others who served Florence had been so completely traumatized by the experience of the air raids - along with the horrific casualties that she may have seen - that her mind and body rebelled against her.

In 1919, Florence was sent to Montreal, Quebec for additional treatment, but eventually she returned home to Halifax for good. She attempted to work, but her condition continued to interfere with her duties. Later that year, it was determined that she could not return to nursing with the military "... owing to her inability of assuming mental responsibility". She was officially discharged in July 1919. By the 1920's, Florence stepped away from nursing entirely. She began working as a clerk at local stores like E. H. Price on Young Street, and later Wood Bros. Co. on Granville Street. She worked at Wood Bros. Co. until she retired in the late 1940's.

Florence passed away on February 12, 1969 at the age of 88. On her death certificate, although she had not practiced medicine for decades, it states that her occupation was "retired nurse". Despite Florence's trauma, her family must have known that being a nurse and serving her country was a personal point of pride for Florence, and it was the way she would have wanted to be remembered.

The Finishing Lines

In the end, Florence lived a long life, which is more than many of those who served during the Great War can say. There can be no doubt. However, her life, like the lives of so many others who served and survived, was forever changed. She traveled to France with the hopes of saving lives, and in a very real way lost part of her own.

When she left Halifax, bound for the European continent, there was no way she could have known the profound effect that the war would have on her and others like her. Her story is a chilling reminder that not all wars are fought on the battlefield, and not all wounds truly heal.

Library Sources

Halifax and Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, City Directory

Personnel Records of the First World War, Government of Canada

Additional Sources

Is Shell Shock the Same as PTSD?, Psychology Today

Nursing Sisters, Government of Canada

Nursing Sisters from Port Hope, A Living Past

Post-traumatic stress disorder, Mayo Clinic

The Shock of War, Smithsonian Magazine

Add a comment to: Gone But Not Forgotten – Part 2: Sister Nurse Florence Louisa MacInnes and The Great War