Though humanity has never been a stranger to bloodshed, the war that began in the warmest days of 1914 would be a conflict like no one had ever seen. Trench warfare changed the geography of mainland Europe forever, governments collapsed under the weight of revolution, and the loss of life was staggering with an estimated ten million people dying over the four-year-long Great War.

Even places as quaint and picturesque as Nova Scotia were not immune to the conflict nearly 5,000km away. Many men volunteered to serve overseas and tragically lost their lives.

World War I: How it began

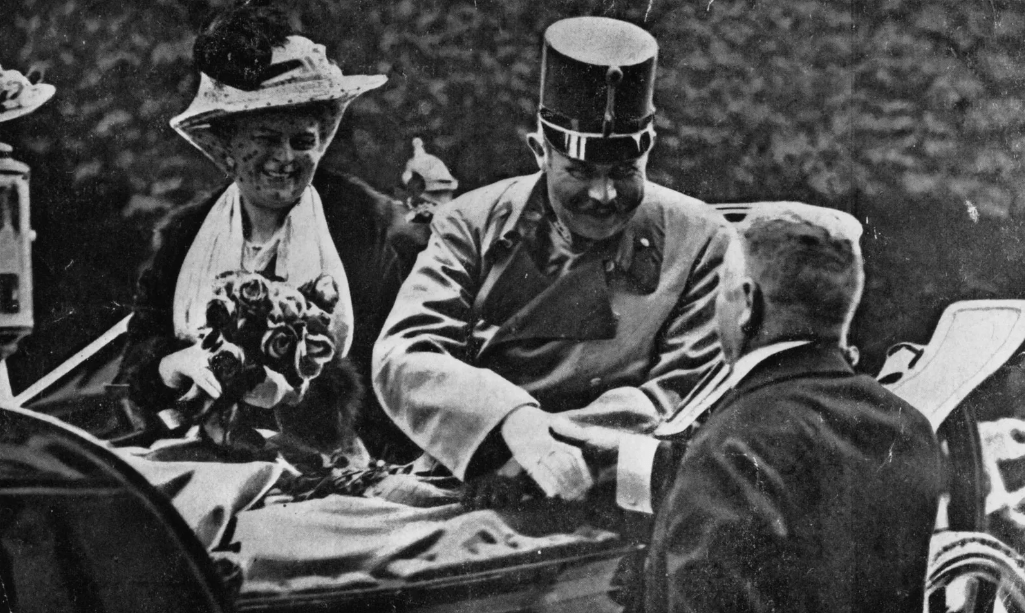

On June 28, 1914, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his consort Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were shot while traveling by motorcade through the city of Sarajevo in the then Austro-Hungarian province of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The gunman, Gavrilo Princip, was a Serbian nationalist who believed that Bosnia should be under Serbian rule, not Austro-Hungary. What followed the assassination was weeks of escalating tensions and violence. Anti-Serbian protests swept through Austro-Hungary, no doubt fueled by Austro-Hungarian leaders who believed the Serbian government had been involved in the assassination plot. Numerous demands and ultimatums were placed on the Serbian government by Austro-Hungary and its ally Germany. Serbia did its best to comply, but emotions ran so high that the situation could not help but come to tragic head. On July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

This sparked an intense chain reaction.

Seeing its Slavic neighbour under attack, Russia began to mobilize its troops. Noting that Russia was preparing for combat, Germany demanded declarations of peace from both Russia and its own neighbour France. When they received silence in return, Germany declared war on them both. In early August, 1914, Germany also invaded Belgium, a country that had been guaranteed boarders of neutrality in the Treaty of 1839. France turned to Great Britain for support. Though they were at first hesitant to become involved, the invasion of Belgium and Germany's failure to retreat from Belgian boarders became the tipping point for the British government. On August 4, 1914 Great Britain joined Russia and France and declared war.

As a part of the British Empire, when Great Britain was at war, Canada was at war.

It is not fitting that I should prolong this debate. In the awful dawn of the greatest war the world has ever known, in the hour when peril confronts us such as this empire has not faced for a hundred years, every vain or unnecessary word seems a discord. As to our duty, all are agreed: we stand shoulder to shoulder with Britain and the other British dominions in this quarrel. And that duty we shall not fail to fulfill as the honour of Canada demands.

~ Prime Minister Robert Borden, 12th Parliament, 4th session, August 19, 1914

At the time, both the Canadian army and navy lacked members and were incredibly ill-prepared for large scale battle. A call went out across Canada for volunteers to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). In the latter part of the war conscription was also utilized to support the military. Between 1914 and the end of the war in 1918 more than 620,000 Canadians were mobilized.

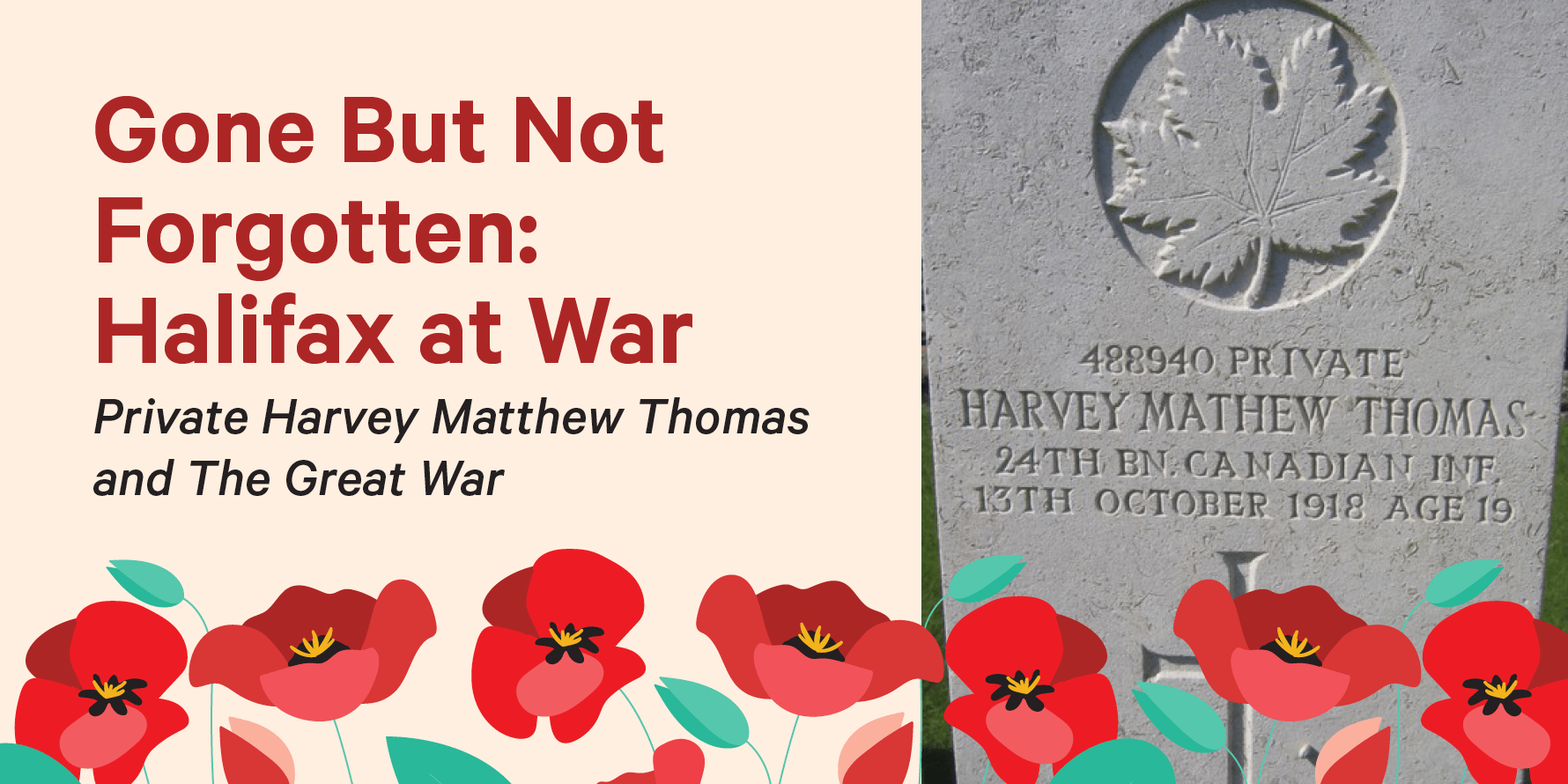

Private Harvey Matthew Thomas (1899 - 1918) - 488940

Harvey Matthew Thomas was born on April 4, 1899. His parents William and Emma Thomas came to Nova Scotia by way of Newfoundland sometime in the late 1800's. William was a carpenter by trade and worked for James Dempster LTD, constructing wooden doors and window sashes. Emma managed the Thomas household of eight children. City directories of the day suggest that the family lived in a number of locations in Halifax including Maynard Street, Atlantic Street, Walnut Street, and Cedar Street. It was the house on Walnut Street that is likely to have been the last home Harvey would ever know.

When the war began in 1914 Harvey was only fifteen years old. He was five foot and seven inches tall, and sported a dark complexion with a head of deep brown hair to match. His eyes stood out against his otherwise dark features as a light and gentle blue. He had three notable scars: one on his forehead and two on his left arm.

The sight of Halifax Harbour filled with ships of war and the city streets packed with men in khaki uniforms couldn't help but make an impression on young Harvey. He no doubt felt a swell of patriotism at the thought of fighting for King and Country and wanted to join those soldiers in their cause. In late 1915, Harvey volunteered for the 63rd Regiment, also known as the Halifax Rifles. This regiment was tasked with local duties, which meant protecting Halifax against attack and invasion by digging trenches, placing wire entanglements, constructing blockhouses and dugouts, and much more. It also meant that Harvey was not sent overseas to fight. He served with the Halifax Rifles for eight months, but by April of 1916 work on the home front was not enough for Harvey; he signed up to join the CEF.

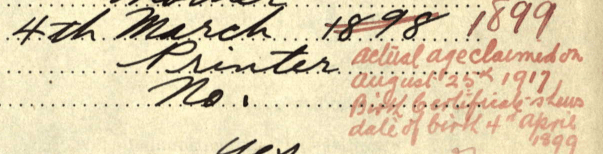

Men applying to serve in the CEF needed to be in good health and between the ages of eighteen and forty-five. Harvey was only seventeen when he applied, so he did what lots of young men did to join the war effort at this time - he lied. On his attestation papers Harvey stated his birthday was March 4, 1898, making him the legal age plus a month for good measure. This lie was later discovered in 1917 when someone in the War Office got their hands on Harvey's birth certificate. A note was made on his file, but by the time the lie was discovered Harvey was already well involved in the fight and there was no going back.

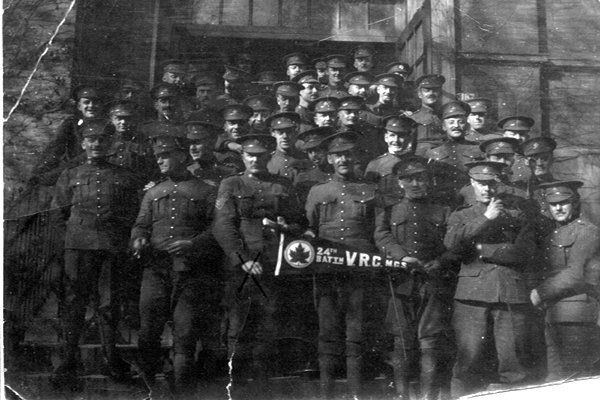

Harvey had his medical examination for the CEF at the military base on McNab's Island in Halifax Harbour. He was determined to be in good health, and was provided with vaccinations against potentially fatal illnesses like typhoid. On July 25, 1916 he arrived in England after a ten day journey at sea. He was "Taken on Strength", or officially accepted into the British Army, on the same day at Dibgate Camp near Kent, UK. Initially, Harvey was brought into the 23th Battalion, but by October 1916 he was placed into the 24th Battalion.

The 24th Battalion of the Canadian Infantry was also known as the Victoria Rifles. The Victoria Rifles were based in Montreal, Quebec, and at the time Harvey joined they were under the command of Lieutenant Colonel C. F. Ritchie.

Before Harvey joined the army he worked as a printer. In 1920, printers in Halifax made approximately $100 per month. In joining the army, Harvey would have taken a significant pay cut. He was paid $1 a day, plus an additional $0.10 per day if he was on the front lines. While he was overseas, Harvey kept very little money for himself and always sent $20 of his monthly income home to his mother.

Harvey spent most of his time in France, but was able to take some leave in order to get a break from the fighting. He visited Warlingham, UK a village about 14km south of London. While he was there he was treated in a military hospital, but the ailments appear to have been relatively minor.

While Harvey was with the 24th Battalion, he got himself into a little bit of trouble.

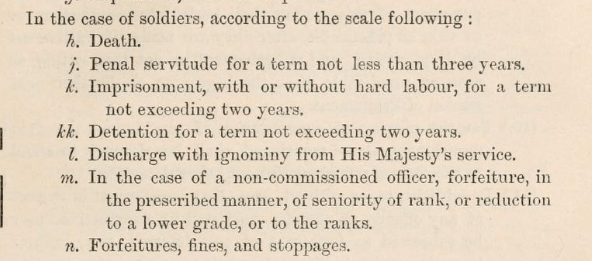

On the evening of July 30, 1917, a "disturbance" occurred in the 24th's camp. As a result, one Private was going to be placed under the watch of the Camp Guard. Harvey was instructed to assist in placing the other Private into confinement, which he refused to do... twice: "I cannot do it Sergeant... I am not going to do guard over my comrades..." (Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada: Courts Martial Records, 1914-1919, slide 4085). In August, Harvey was courts-martialled for his actions under Section 8(2b) of the Army Act found in the Manual of Military Law. Section 8 specifically refers to a soldier who: "Strikes or uses or offers any violence to his superior officer, or uses threatening or insubordinate language to his superior officer" (p. 274). Harvey was sentenced to forty-two days of Field Punishments (FPs). FPs took different forms depending on the severity of the incident, but could include being tied to a fixed object for up to two hours a day, being placed in irons (handcuffs or fetters), hard labour, etc.

On October 12, 1918, Lieutenant Colonel Ritchie received word that the 24th Battalion was to march on the French town of Hordain. He had been instructed to capture the town and establish a line of resistance against the German army north of town. At 8am, the Battalion marched from the town of Ramillies to Hordain approximately 9km away. Although they had expected severe opposition from the German troops, Hordain was captured with very few casualties. On the opposite side of town, however, the German forces were waiting. Machine-guns and artillery fired at the 24th Battalion and though they held on and were able to establish a new defensive line many of the men in the Victoria Rifles were killed. It was sometime during this push through Hordain that Harvey lost his life.

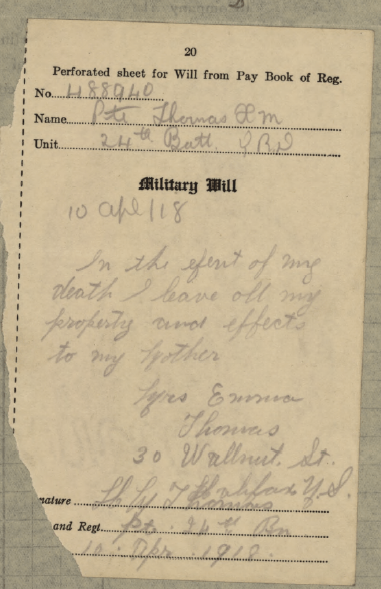

Harvey was declared killed in action on October 13, 1918. He was just nineteen years old. In his will he left everything he had to his mother.

Had he been a ranking officer, his family would have been notified of his death by telegraph - the fastest method of communication at the time. As it was, Harvey's mother, father, and siblings were notified of his passing by letter, which may have taken weeks to arrive in Halifax. In a strange way, Harvey's death was a lucky one. Many soldiers who died in the war were never found, or were simply buried in the fields where they fell. This was not the case for Harvey. His body was recovered and was taken to a nearby town to be interred.

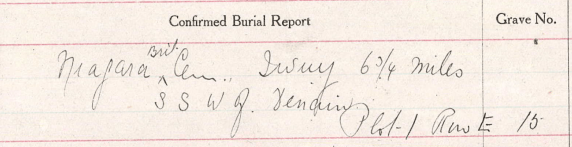

He was buried at Niagara Cemetery in the French city of Iwuy, Plot 1, Row E, Grave 15. The inscription on his tombstone was chosen by his family and reads: "Not gone from memory/Nor from love/Gone to our Father's home above".

In his death, Harvey was awarded the Memorial Cross.

World War 1 ended with the signing of the Armistice agreement on November 11, 1918, a mere twenty-nine days after Harvey was killed.

The Finishing Lines

The Thomas family, like so many other families, were left with an empty seat at their table. The joy of a four year war coming to an end was over-shadowed by their grief; a young life lost thousands of miles from home, buried on foreign soil. Perhaps they took consolation in the idea that Harvey died for a greater cause - that his life helped bring peace to a war torn world.

Would they continue find solace when just over twenty years later war would once again flood over Europe?

Library Sources

Halifax and Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, City Directory

Nova Scotia's Part in the Great War

Additional Sources

Boys! Come Along You're Wanted, Nova Scotia Archives

Canada and the Beginning of the First World War

The Canadian Great War Solider, The Canadian Encyclopedia

City of Halifax Civic Address Conversion, Halifax Municipal Archives

Commonwealth War Graves, Thomas Harvey

Company Sergeant Major Robert Lindsay, Government of Canada

Conscription in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia

Court Martial of the First World War, Library and Archives Canada

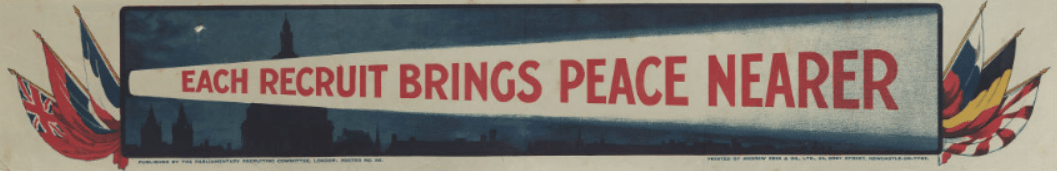

Each Recruit Brings Peace Nearer, Nova Scotia Archives

Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este, Britannica

The Great War, 1914-1918, War Graves on the Western Front

How many people died in WW1? A look at the numbers

The Long, Long Trail: Researching soldiers of the British Army in the Great War of 1914-1918

Manual of Military Law, Library and Archives Canada

Military Justice, International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Nova Scotia and the First World War, Nova Scotia Archives

Personnel Records of the First World War, Government of Canada

Rally Round the Flag, Nova Scotia Archives

Urban Working-Class Incomes and Real Incomes in 1921: A Comparative Analysis by Michael J. Piva

Add a comment to: Gone But Not Forgotten – Part 1: Private Harvey Matthew Thomas and The Great War