Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window

On April 15, 1912, an article appeared on the front page of the Halifax Herald. “THE TITANIC IS STRUCK BY AN ICEBERG” the headline read, followed by four short paragraphs telling readers that nearby ships–like the Virginian–were changing course and heading to the Titanic’s location to offer assistance. It is clear from this brief story that the full gravity of the Titanic’s situation was not yet clear, and that the devastating news of the hundreds of lives lost was yet to come. Among the dead was prominent Dartmouthian, George Henry Wright. Let’s take a look at his life, how he came to be on the ill-fated vessel, and how his death affected our community.

The Wright stuff

George Henry Wright was born in Wright’s Cove in Dartmouth, on October 25, 1849. His father, George William Wright (1816-1856) and mother Bridget (Lowe) Wright (1823?-1856?) ran a successful farm in the area, and made a good living; but their son was not interested in following in his parents’ footsteps. At the age of 17, Wright left his home in Dartmouth, and travelled to the United States in hopes of making his fortune.

Once described as an “incipient genius for compilation,” Wright put his skills to use while in America. He began collecting information to assemble a shippers’ guide for businesses in the United States. This endeavour took him all across the U.S.A. and enabled him to form relationships with many entrepreneurs. The guide was a financial success—but it would be only the beginning of his life’s work.

In 1876, Wright attended the U.S. Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The Exhibition was the first World’s Fair held in the United States. It took ten years to plan and featured displays about art, manufacturing, farming, mining, and more from each of the American states, as well as 37 different countries. It was here, particularly after seeing the displays from Australia, that Wright was inspired to expand his shipping directory to include more of the world at large. Later that year, he set sail for Australia and New Zealand.

Globetrotting

Wright’s expedition in Australia was a laborious one. The terrain was difficult, the lodgings were not always comfortable, and the days were long—but he was dedicated to his idea of a world directory. In the Evening Mail, Wright is quoted as saying: “The difficulties seemed overwhelming and the whole prospect dreadfully disheartening, but I had made up my mind to succeed, and stuck right to it.” From Australia and New Zealand Wright travelled to Singapore, Burmah (Myanmar), “Further India” (Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia), and India. He then began his journey home by passing through the Middle East, Italy, France, and finally to England where he booked passage back to New York.

Once settled in New York, Wright began the publication of his directory through the firm Thomas Cook and Sons. He titled it “Wright’s World Business Directory,” and it was an instant hit. Full of useful information and business advertisements, the Halifax Herald called the book “invaluable to merchants and manufacturers seeking to extend their trade.” As soon as the book was published, Wright returned to Australia with his brother to distribute the guide. When he arrived, the people were delighted with the product, but also a little surprised that he was able to complete his task. On this trip, Wright began gathering even more information for a second edition, once again travelling those places he had previously visited—adding Japan to his trip as well. Between 1880 and 1899, Wright would publish 5 editions of the directory, which were composed of some 4,000 pages.

Though the completion of his World Business Directory was his ultimate goal, Wright also found himself creating guides specifically for England. He published two souvenir books for the World’s Fair in 1893/94, one of which focused on English textile trades, and the other on engineering and metal trades. These publications were over 400 pages long, and included historical information about London accompanied by illustrated sketches. The book also featured advertisements by some of Britain’s well-known firms like Rylands and Sons of Manchester and London, Elkana Armitage of Manchester, Horrocks of Preston, and more. Wright stated that though some businesses were hesitant to advertise in the book, once a few major organizations bought in, most of the rest followed.

Coming home again

Wright was certainly a man of the world, but he never forgot where he came from. In 1896, he returned to Halifax and shifted his focus to improving the community where he grew up. As one of his first tasks, Wright, along with architect James Charles Dumaresq, constructed two office buildings. The first being the St. Paul’s building on the corner of Barrington and Prince Street, and the other, just two doors down, The Wright Building (also known as The Marble Building). On these buildings, the Evening Mail reported:

The Marble block and the St. Paul buildings are the two finest and handsomest business blocks, not only on Barrington Street, but in the city of Halifax… They offer to the public not only splendid stores, but excellent chambers and office accommodation, as well as a handy-sized and elegantly-finished assembly room.

—Evening Mail, December 27, 1897, page 9.

The buildings featured many modern conveniences of the day, including elevators, electric lights, and steam heat. Additionally, the clock tower that once stood on top of the roof of St. Paul’s connected to clocks on every floor in the building, ensuring tenants and the public knew the correct time of day.

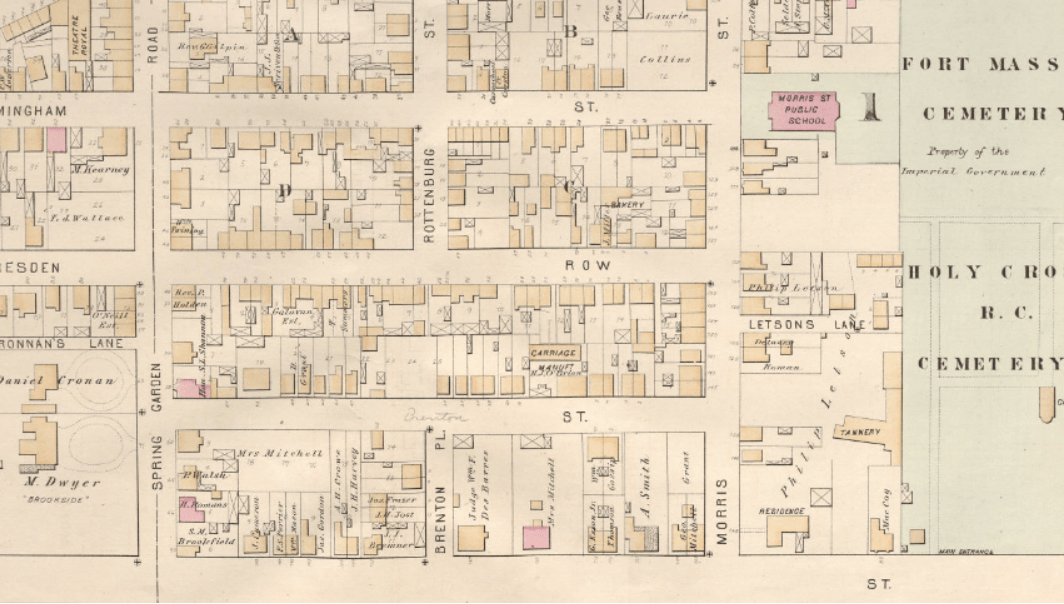

Wright did not focus solely on the construction of commercial properties. He was a vocal spokesperson for the city’s poor and underprivileged; particularly its women and children. He believed that all people were entitled to proper housing, which lead him to develop what’s considered to be Halifax’s first housing project. Upon the death of local tanner Phillip Letson, Wright purchased a plot from Letson’s estate at the corner of Morris and South Park Streets. He removed the tannery buildings, and with Dumaresq began renovating the remaining property. When he finished, they had constructed 18 homes on South Park Street, Morris Street, and Wright Avenue (previously Letsons Lane).

The houses facing South Park Street were generally larger, more elaborate dwellings in the Queen Anne Revival style that was popular at the time, but many others were simpler and built with the working Haligonian in mind.

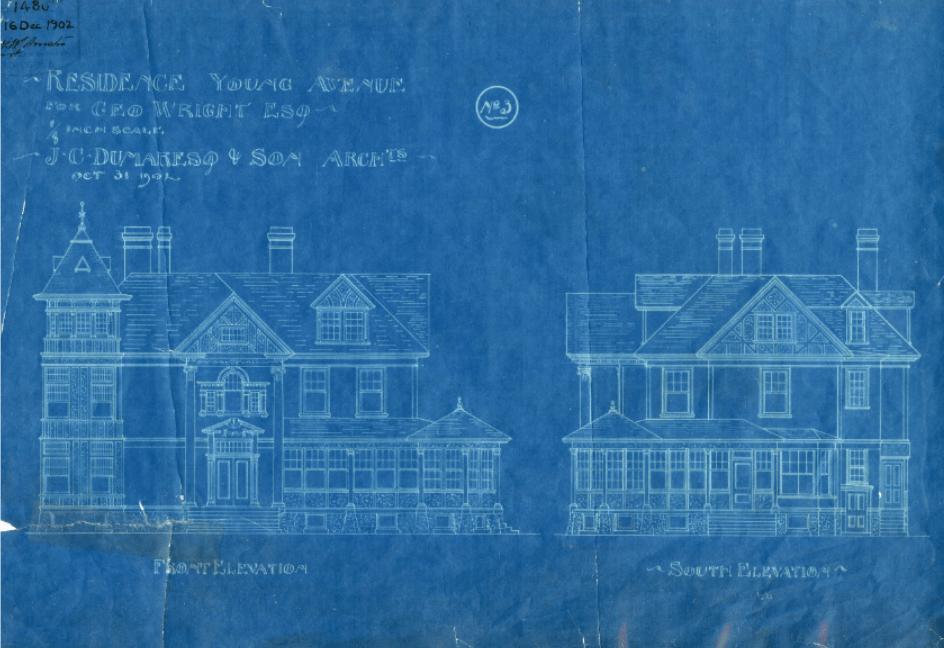

Not to forget himself, Wright and Dumaresq also constructed a beautiful home for Wright on Young Avenue. At a cost of $10,000, this Queen Anne Revival home was completed in 1903. The mansion included a library, sunroom, parlour, living room, kitchen and pantry, 3 bedrooms, two baths, and a dressing room. The attic and basement contained a larder, furnace room, laundry area, a toilet, and a servant’s room, believed to be where his chauffeur/butler lived. As Wright was a lifelong bachelor, this living situation led to rumours that Wright had a relationship with his employee, but that has not been confirmed.

In addition to these housing projects, Wright was also well-known as a philanthropist. The Halifax Herald stated that Wright “…never gave an unsympathetic ear to a hard-luck story or appeal for help, no matter whence it came, so long as he thought the need was real. He was every ready to help, and he helped quickly. His hand was always in his pocket. There was no philanthropy in the city to which he did not contribute if its wants were made known to him.” In true Victorian fashion, Wright was also an advocate of morality, with strong opinions against the use of profanity, prostitution, and what he considered to be ‘cheap’ entertainment in local theatres. In 1911, Wright wrote to Halifax City Council suggesting that a by-law be introduced that would prohibit “demoralizing pictures and… indecent vaudeville shows”, and that theatres would instead show “high class and instructive amusements.” He was also known to write letters to the New York Times expressing his views.

An ill-fated trip

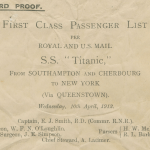

In the fall of 1911, Wright booked passage on the Empress of Ireland and travelled Europe with his friend C. W. Frazee. He was in Paris when he heard about the Titanic’s maiden voyage, and it appears his passage back to New York on the luxury liner was booked at the last moment as his name does not appear on the final passenger list.

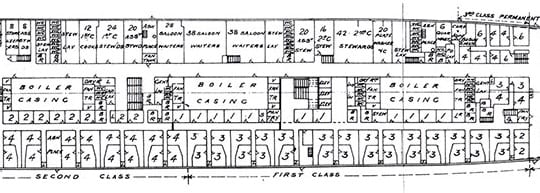

Though it is not known exactly which cabin belonged to Wright, it is known that he purchased a First Class, single-berth cabin at a cost of £26 (ticket number 113807). These cabins were found on the E Deck of the ship, near the middle of the vessel. First Class rooms were placed in the middle of the ship as this location was less likely to feel the effects of the waves compared to the stem and stern, making for a smoother, more enjoyable voyage.

In the very early hours of April 15, 1912 the Titanic collided with the iceberg that would seal its fate. When the true reality of the disaster was reported, and it was discovered that Wright had been among the victims of the tragedy, The Halifax Herald reported: “There is now no doubt that George Wright is among those who went down with the Titanic, heroically standing aside like the others to allow the women and children into the boats – themselves facing certain death.” This paints a portrait of a brave man who was obviously revered by the town that lost him, but when survivors were later questioned about Wright’s presence on the ship, no one could recall seeing him. Frazee would say that Wright was inclined to keep to himself, and was also an incredibly heavy sleeper. It was speculated that Wright went to bed on the evening of April 14 and either drowned in his sleep, or woke up too late to escape his cabin. However, Frazee would also state that if Wright had woken in time, he would have been that man who stood to the side to save the lives of others.

Wright’s body was never recovered, or at least never identified, but his brother arranged for a headstone to be placed in Christ Church Cemetery in Dartmouth.

The reading of the will

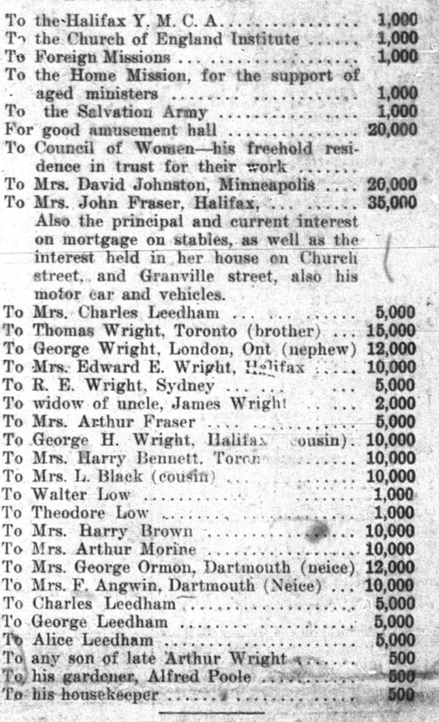

On April 9, 1912, the day before the Titanic left port, Wright met with his lawyers in London. It was during this meeting that Wright composed a will, which would donate thousands of dollars to his family, friends, and various charities.

Some of the most notable charitable donations include $1000 each to the YMCA, the Church of England Institute, and the Salvation Army. He also set aside $20,000 to build an amusement hall “…to provide for a higher form of amusement than is at present placed before the people, and for a building to be erected for the purpose of bringing the people together to uplift and train them to higher ideals, such building to be also used for meetings, lectures, and to provide clean amusement in order to check the lure and bad influence of the streets…” This donation was held by the city until the 1950s, where the money – which had then grown to around $85,000 – was given to the YMCA after a judge’s ruling.

One particularly notable bequest was that of his home on Young Avenue, which was to be held in trust for the Local Council of Women in Halifax. This chapter of Council had formed in 1894, and was dedicated to directing positive change for women, including helping them win the right to vote. According to their website, the Council states that Wright “…wanted them to have a proper place to meet, allowing them to continue the work that they were doing. For many years, “The George Wright House” has been a meeting place for community groups for meetings and special events for women in the city.” To this day, the Council continues their good work from Wright’s home.

Looking forward

Although Wright started his life with a solid foundation, it was truly his dedication and drive that made him a success. Whether or not one agrees with his strict Victorian views, Wright had a vision for Halifax and Dartmouth that included the betterment of everyday life for the poor and working class. Through his generosity, charity organizations received much-needed financial support to help make positive changes in the city, with some benefiting from his gifts over 100 years later.

Library Resources

Halifax and Titanic by John Boileau – 910.91634 B679h

Titanic Remembered: The Unsinkable Ship and Halifax by Alan Ruffman – 910.91634 R923t

Titanic by Jim Pipe – 910.91634 P664t

In the Wake of the Alderney: Dartmouth, Nova Socita, 1750-2000 by Harry Chapman – 971.6225 C466i

Historic Young Avenue and Some of its Heritage Treasures by Young Avenue District Heritage Conservation Society – 971.6225 Y687

Anatomy of the Titanic by Tom McCluskie – 623.82432 M478a

Halifax Chronicle Herald Microfilm: “Hilda, George, and the Iceberg” April 12, 2007 page A7

Halifax Evening Mail Microfilm: “George Wright’s Worth Example” December 27, 1897 pages 9 and 10

Halifax Herald Microfilm:

“The Titanic is Struck by an Iceberg” April 15, 1912 page 1

“Halifax Loses Good Man in George Wright” April 20, 1912 pages 1 and 2

“George Wright’s Will Provides for Bequests of about $275,000” May 7, 1912 page 1

Ancestry.com Library Edition

Online and Community Resources

Canada's Historic Places: George Wright House, opens a new window

Find a Grave: George Henry Wright, opens a new window

Encyclopedia Titanica: George Henry Wright, opens a new window

GG Archives: Decks of the Titanic: Comprehensive Details - 1912, opens a new window

Encyclopedia Titanica: Titanic Deckplans : RMS Titanic : Plan of E Deck, opens a new window

George Wright: A Most Notable Dartmouth Native , opens a new window

Historic Nova Scotia: George Wright (1849-1912) A Notable Dartmouth Native, opens a new window

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic: Titanic Remembered Bibliography, opens a new window

The Globe and Mail: Mysterious Haligonian lost on the Titanic made quiet exit, opens a new window

THE LOCAL COUNCIL OF WOMEN HALIFAX: The George Wright House, opens a new window

Halifax Rainbow Encyclopedia: George Wright, opens a new window

Halifax Heritage Property Program , opens a new window

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Centennial Origins: 1874–1876, opens a new window

Nova Scotia Archives, photographs and maps, opens a new window

Halifax Municipal Archives, Legacy Content, opens a new window

Halifax Council Minutes, January 5, 1911, opens a new window

Halifax Council Minutes, December 19, 1912, opens a new window

Halifax Council Minutes, October 31, 2011, opens a new window

Add a comment to: George Henry Wright and the Sinking of the RMS Titanic: A Brief and Not at All Definitive History