Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window

In 2018/2019, it was projected that the people of Halifax would ride the bus 17.5 million times. The year before: the number was similar, and it was similar still the year before that. Turns out, Halifax and nearby communities have had a historic love affair with public transit. Let’s take a look at how it all began!

The 1860/70s

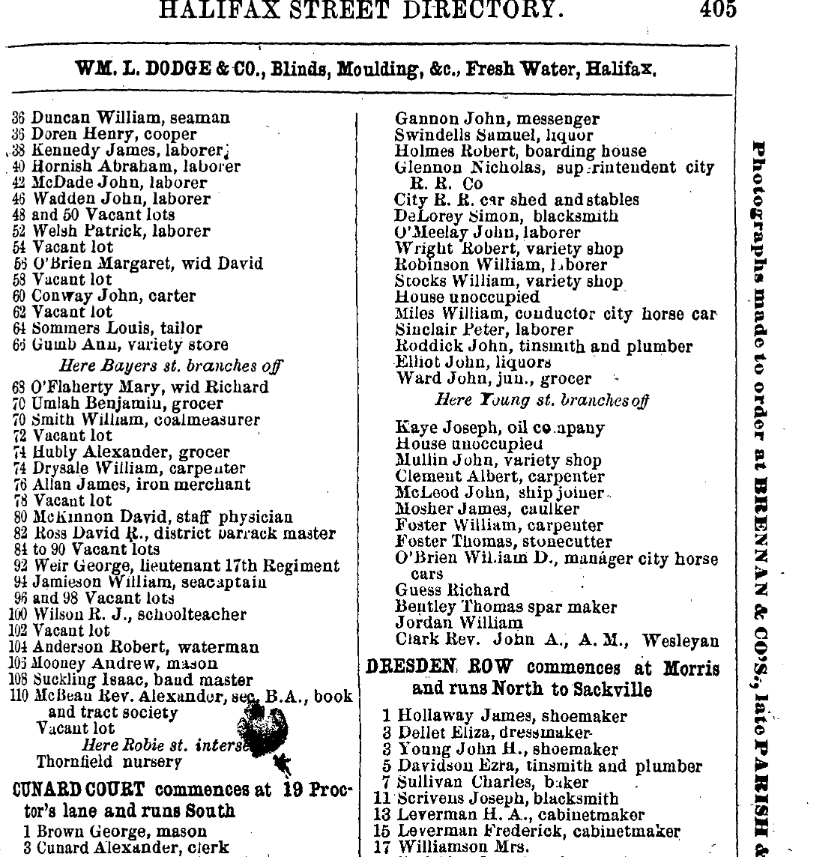

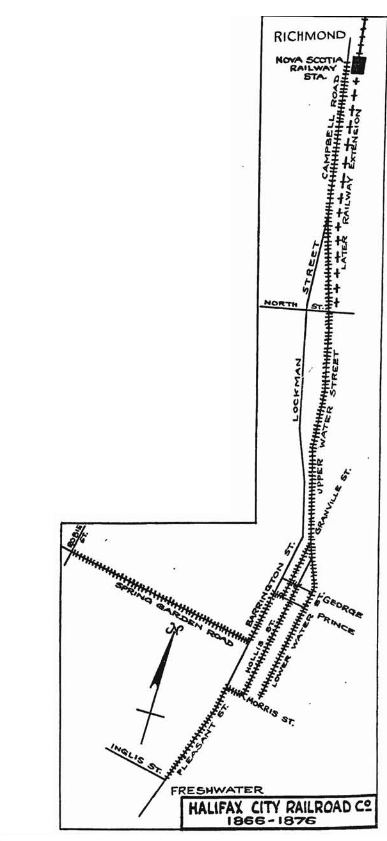

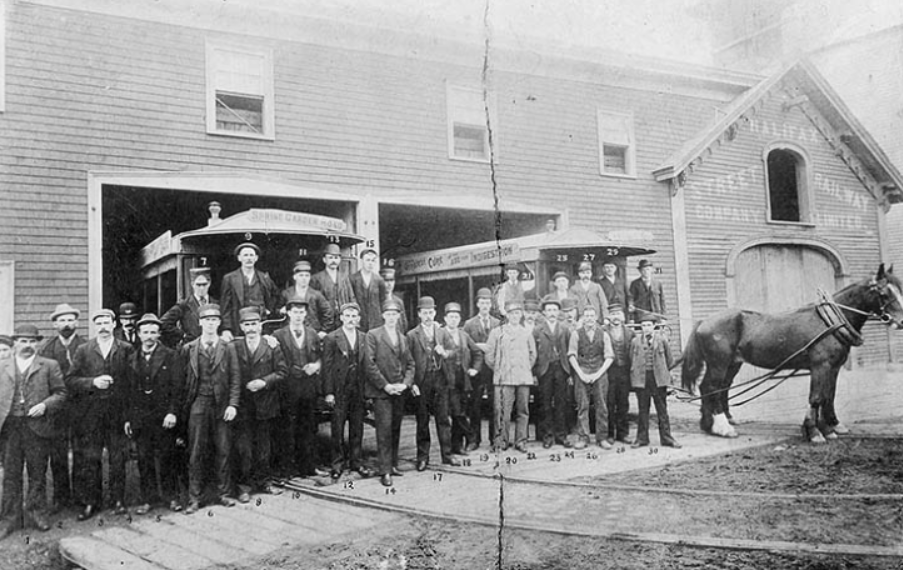

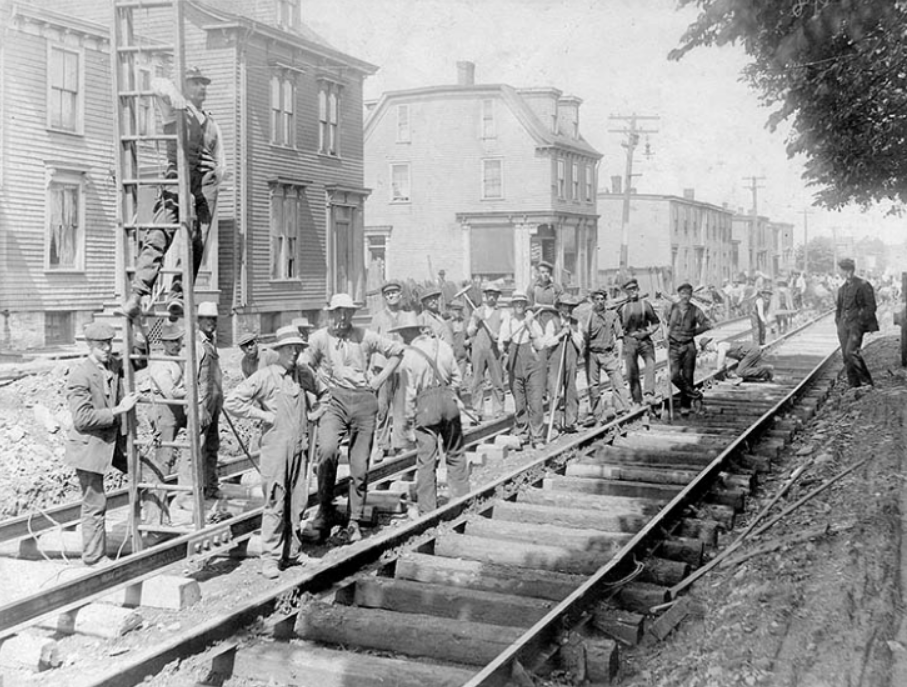

Prior to the 1860s, public transportation in Halifax relied on horse-drawn cabs and coaches. At a rate of $0.35-0.65 per person, they were not something every citizen could afford. In 1863, William D. O’Brien made the decision to try a public transport system in the city, creating the Halifax City Railroad Company. It took three years for construction to begin, but within the course of a few months, O’Brien and his workers laid track for a horse-pulled railway.

The railway opened to much fanfare in June of 1866. The Acadian Recorder stated that “…an immense concourse of people gathered near the Province Building at 12 o’clock on the day mentioned to view the cars as they were driven over the line for the first time. The pleasant faces of both old and young, white and black, showed with what delight our people hailed the undertaking…” When the railway settled into its routine schedule, regular hours ran from 6 am-10 pm, with no service on Sunday. The cost was twenty tickets for $1, or $0.07 for a single adult ticket and $0.03 for a child. As time went on, the service was so popular that additional track was laid to accommodate a route on Spring Garden Road up to Robie Street, as well as service to the newly developing Windsor Park. Larger cars with sturdier rails had to be implemented on certain routes in order to carry the large number of passengers using the railway.

Unfortunately, O’Brien’s endeavour would only last a few years. In 1876, the Intercolonial Railway made plans to lay track further into the city. In order to do so, they needed to excavate part of Campbell Road and Water Street, which would mean the removal of some of the Halifax City Railroad Company’s tracks. O’Brien attempted to negotiate with the Intercolonial Railway but met with little success. Ultimately he abandoned the business and sold off the cars and his horses.

The 1880/90s

Though coaches, cabs, and the occasional omnibus were available for use, Halifax went without public transportation for nearly ten years. This changed in 1886 when a group of three Americans – E. F. Camp, John F. Zebley, and John R. Bothwell – formed the Halifax Street Railway Company. This venture opened in October of that same year. The cars ran every 15 minutes at a cost of $0.05/person. In rough weather, these cars were fitted with plows for snow clearing, but they were not especially safe. Staff were required to stand on the back of the plow blades to keep them on the ground. In particularly bad storms, the plows would jump the rails and knock people into the snowbanks!

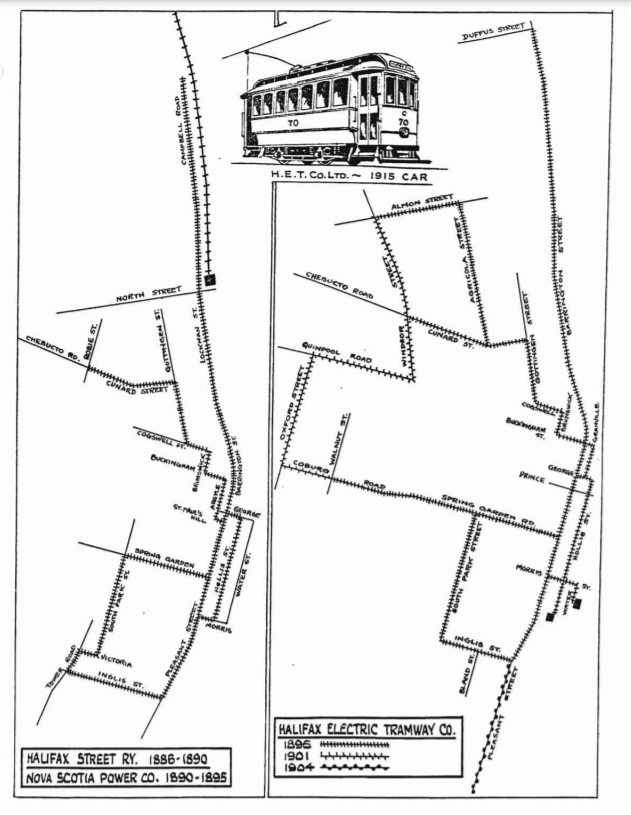

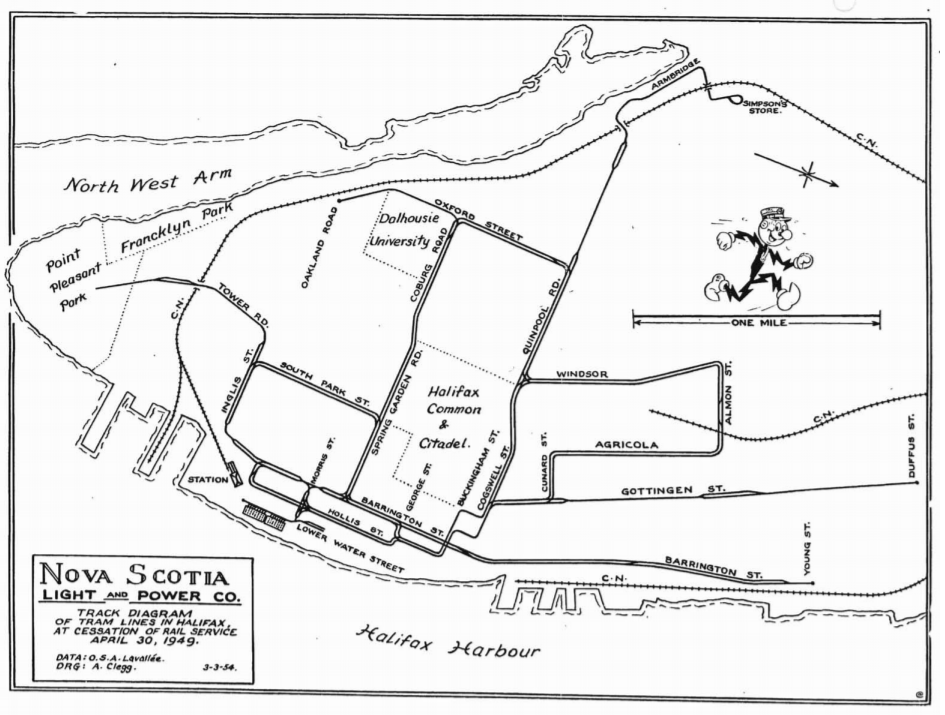

As much as the horse railway system was a benefit to Halifax, by the 1890s all anyone could talk about was an electric trolley system. In 1895, the Halifax Electric Tramway Company was founded. This Company purchased the Halifax Street Railway Company, as well as the relatively new Nova Scotia Power Company, for $25,000. They also purchased the Halifax Illuminating & Motor Company, which supplied the city with power. With these forces combined, they were able to start the task of installing the power poles and electric cables that would fit the city for an electric tram.

A new depot was built on Water Street capable of housing thirty cars. The fleet was composed of both open and closed style carriages. These, along with trucks and some electrical equipment, were purchased from Rhodes, Curry & Company in Amherst, NS. The first of the carriages arrived in February 1896, and by May of that year, the horse-drawn railroad made its last run.

The 1900/10s

Throughout the early 1900s, the electric trolley system expanded rapidly. Connections were made to service Willow Park, Greenbank, Steele’s Pond, Armdale and much more. However, with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, all expansion to the tram system was put on hold. Despite the war, or perhaps because of it, Halifax was a bustling seaport, and the use of the trams did not dwindle. As the war waged on, literal manpower became difficult to find. This led the Company to hire a number of women to act as conductors. It was also during this time that the Company changed its name to the Nova Scotia Tramway and Power Company.

On December 6, 1917, tragedy struck the city as the French ship Mont Blanc and the Norwegian ship Imo collided in the harbour. The resulting explosion destroyed much of North End Halifax, killed some 2,000 people, and injured at least 12,000 more. For the Nova Scotia Tramway and Power Company, the disaster resulted in the injury of several employees, the damage and destruction of passenger cars, and downed poles and power lines. Power had to be cut to the lines for a number of days in order to facilitate repairs. Reconstruction was slow going, but by the end of the decade, the system was more or less back on track.

The 1920/30s

Now that the war was over, the Nova Scotia Tramway and Power Company took stock of their business and decided that it was time to replace some of their old carriages. Twenty-four trolley cars called Birneys were purchased as the new fleet. Birneys were small, but they were lightweight, inexpensive to purchase, and efficient to run as they only required one person to operate. Initially, the Birneys were a dark green colour, but people found them difficult to see in the dark, or the fog. They were repainted orange, but the colour was considered too ugly. Ultimately, they were painted a friendly and visible canary yellow. Birneys were exceptionally popular in Halifax. As other cities began selling off their cars, Halifax scooped them up, until eventually, the entire fleet of cars were Birneys. The cost to ride a Birney in 1925 was $0.10 for adults and $0.05 for a child. In 1928, the Nova Scotia Tramway and Power Company rebranded and became the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company.

The 1930/40s

The end of the 1930s brought the beginning of World War II. Once again Halifax became a bustling hub of wartime activities, with the population doubling from approximately 60,000 to around 120,000. The Birneys that had easily shuttled upwards of nine million passengers a year around the city found themselves now needing to carry 31 million. Though additional cars were purchased, it became almost impossible to keep up with maintenance issues – the Birneys simply weren’t built to handle the high demand. When the war ended, the Company made the decision to scrap the 86 car Birney fleet.

Despite their issues, the citizens of Halifax loved the Birney Cars and were sad to see them go. On March 26, 1949, the Birneys ran downtown for the last time. Car Number 177 was decorated for the occasion, with two poems written on it:

“Good-bye my friends, good-bye! Good-bye, my friends, this is the end; I’ve travelled miles and miles And watched your faces through the years, show anger, tears and smiles; Although you’ve criticized my looks And said I was too slow, I got you there and brought you back, Through rain and sleet and snow.”

“Farewell to all you motorists, To-day my journey ends! So let’s forget past arguments, Shake hands and part as friends. You’ve followed me around the streets And many times you swore Because I beat you to the stop And dared you to pass my door!”

Many people – from as far away as Florida – reached out to the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company hoping to purchase the decommissioned Birney cars, but the Company refused to state that after their years of service they had earned the right to be scrapped, rather than be sold and run the risk of being poorly managed and maintained.

The 1950s-1980s

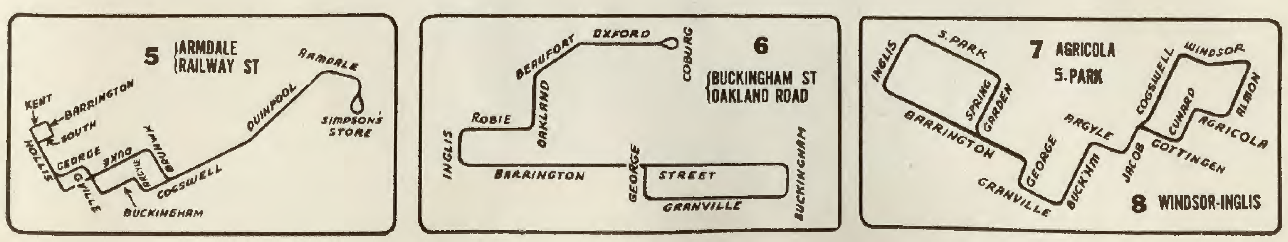

At a cost of nearly $2,000,000, the Birneys were replaced with larger trolleycoaches. These yellow and cream trams were chosen for a number of reasons, including their hill-climbing abilities, noiseless operation, and larger cabin space. The electric coaches were very popular. Even with the increasing number of cars on the road, the trolleycoaches were still carrying upwards of 27 million passengers per year. Though it might have been expected for fares to increase on the new trolleycoaches, the cost remained the same as a ride on the Birneys until the mid-1950s.

Unfortunately, the 1960s brought about difficulties for the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company. Experiencing high losses, they approached the city asking for financial assistance in the form of a subsidy, or to be bought out entirely. A review of the public transport system called the Urwick Currie Report was conducted. The report praised the Company and their employees for their hard work, but ultimately concluded that they could not keep up with their current route schedules and with how fast the City of Halifax was growing. The report recommended that the city purchase the transit system at a cost of $500,000. It was also suggested that the city begin a transition to diesel buses, a switch that would be integrated over the next 5-7 years. Though many of the recommendations of the Urwick Curry Report were quickly put into action, the establishment of a City Transit Commission did not occur until April 1969.

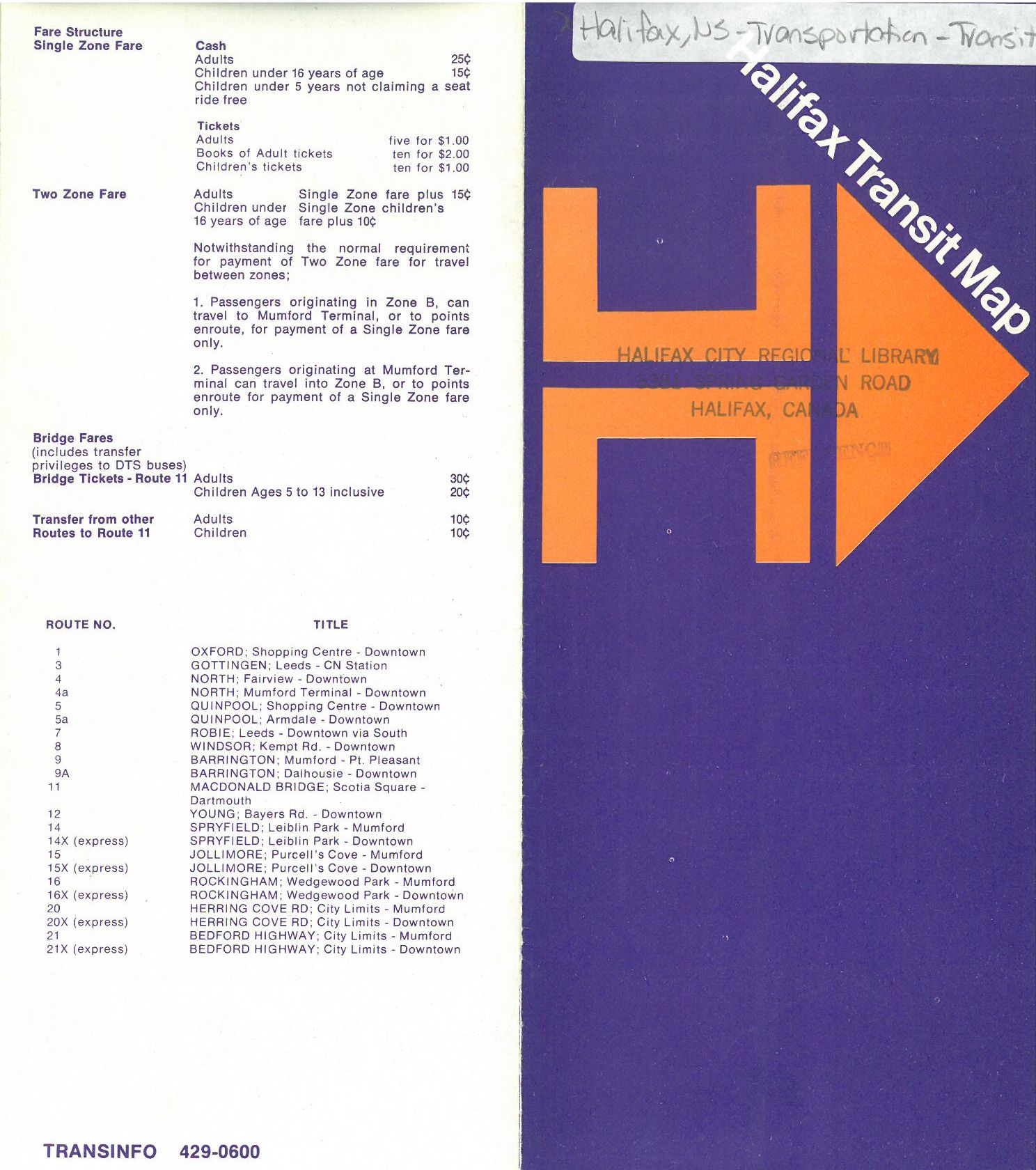

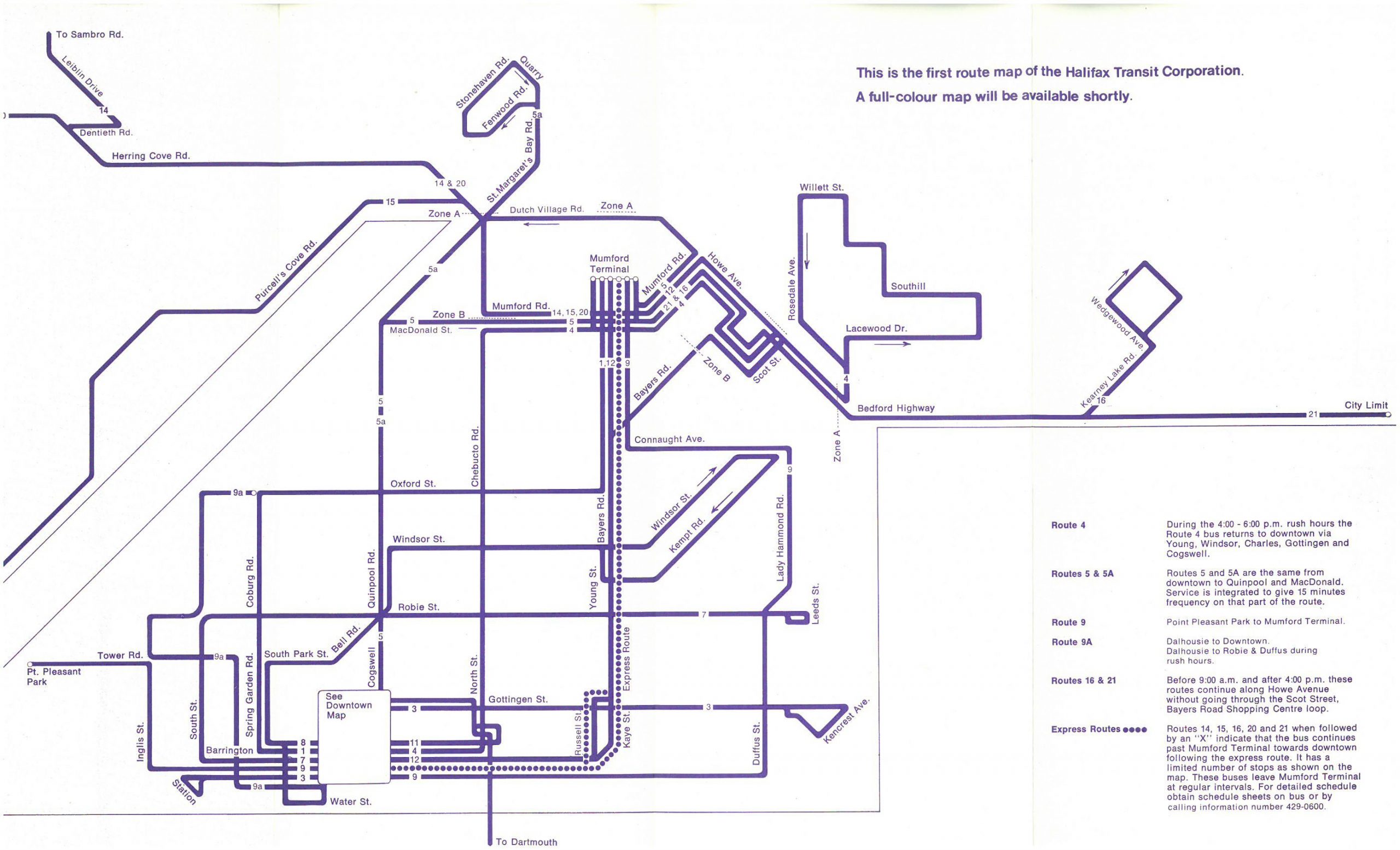

It was decided that the official handoff from the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company to the City of Halifax would happen on January 1, 1970. In preparation, twenty 35 foot and fourteen 40 foot diesel buses were purchased at a cost of approximately $1,285,000. Initially, the trolleycoaches were to be phased out gradually, but after further consideration, it was decided this was not possible due to the overall condition of the trolleys and the plans for completely new bus routes. 40 more buses were bought to facilitate an immediate changeover. Many citizens worried about the environmental impact the buses would have on the city, as well as the noise pollution they created. It also sparked a feud with Acadia Lines, a charter bus service that had been serving the outer areas of the city. Nevertheless, on December 31, 1969, driver Bill Forbes made the last run in an electric trolleycoach, pulling into the Young Street Station for the last time at 12:45 am New Year’s Day. From that point on, the purple and orange buses of the Halifax Transit Corporation hit the streets. The cost of a basic bus ticket rang in at $0.25 for adults and $0.10-0.15 for kids; these prices would increase if you needed to cross the bridge to Dartmouth. Forbes remembers how emotional citizens were at losing the trolleycoaches: “People cried; honest to God they cried.”

Unlike the Birneys, the trolleycoaches were sold off. Most of them were used to supply parts to transit systems in Toronto. One car, however, was donated to the Trolley Museum in Kennebunkport, Maine. Trolleycoach 273 was donated to the museum in 1971 by the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company, along with some spare parts and other equipment. Forbes took a trip to the museum in 2013, but discovered the trolley was not kept in good shape: “It was rusting, the bumper was half off… When they took it they said it was going to a museum, but it’s in a yard – the graveyard they call it.”

By 1979, the now named Metro Transit had its sights set on a fully integrated public transit system that covered Halifax, Dartmouth, and greater Halifax County. The Metropolitan Area Planning Commission (MAPC) agreed on the construction of a new facility for transit operations and maintenance, to be located in Dartmouth not far from the MacKay Bridge. The venture had a projected cost of $7.1 million dollars. The rest, as they say, is modern history.

So what?

There have certainly been lots of changes since the 1970s – even discussions of returning to a rail system. But through it all, Halifax has remained a city of active, busy, buses. Catering to thousands of users, they are absolutely essential to everyday city life. Whatever the future holds for public transportation in Halifax, you can bet that people will be hopping on board.

Online Resources

Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

The Coast: Streetcar Desires, opens a new window

Halifax Transit: Trolley Bus Service in Halifax, opens a new window

Skyrise Cities: Once Upon a Tram: The Halifax Street Railway, opens a new window

Global News: Digging up the past: Halifax’s buried rail tracks make way for progress, opens a new window

Seashore Trolley Museum: TRACKLESS TROLLEY 273, opens a new window

Library Resources

“Halifax, City of Trolleycoaches” by Paul A. Leger 388.46 L512h

“Trams and Tracks” by Russ Lownds 388.46 L919t

“Golden Jubilee Division 508 Amalgamated Association of Street, Electric, Railway and Motor Coach Employees of America (A. F. of L. – C.I.O.) Affiliated with Halifax and District Labour Council, Nova Scotia Federation of Labour, Canadian Labour Congress: 331.8811388322 G618

Halifax Birney Stronghold by Robert R. Brown 388.46 B879h

“The Halifax Street Railway” by Don Cunningham 388.46 C973h

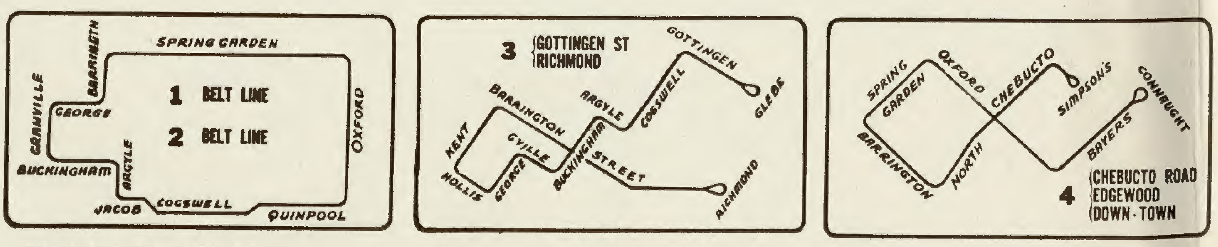

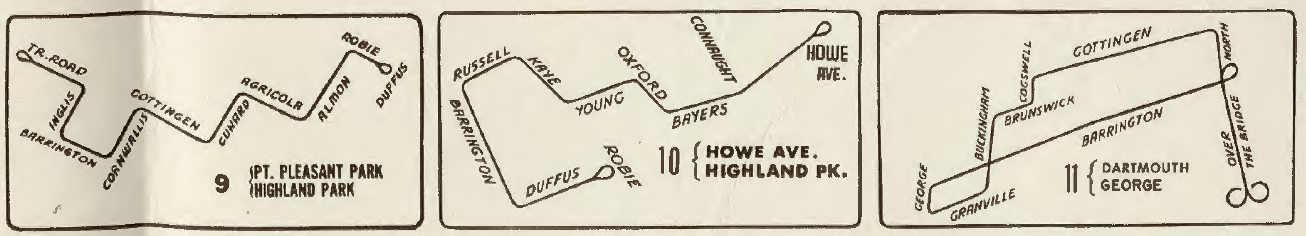

Trollycoach Map

Vertical Files: Halifax, NS – Transportation

“The Classic Transit Days” by Peter Clarke, Chronicle Herald, Dec. 31. 2013

“Shopping, Transit Boost Aim of Downtown Scheme” by Jill Rafuse, Halifax Mail Star, Sept. 30, 1975

“Transit Plans in Final Stage” by Jim Axell, Chronicle Herald/Mail-Star, June 15, 1979

Transit Map, 1970s

Add a comment to: From the Birney to the Bus: A Brief and Not at All Definitive History of Halifax Public Transit