Written by staff blogger, Vicky

Historical research is the original Wiki-hole.

You start out casually researching information for one topic, but along the way, you find something else that is fascinating, which leads to yet another thing... and another. Before long, you have fallen into a deep chasm, and you're fully distracted from your original goal. Sometimes you never truly stop falling, and your distractions seem to go on forever. Other times you abruptly hit a hard bottom all because you stumbled across two words in a Halifax city directory:

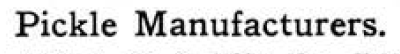

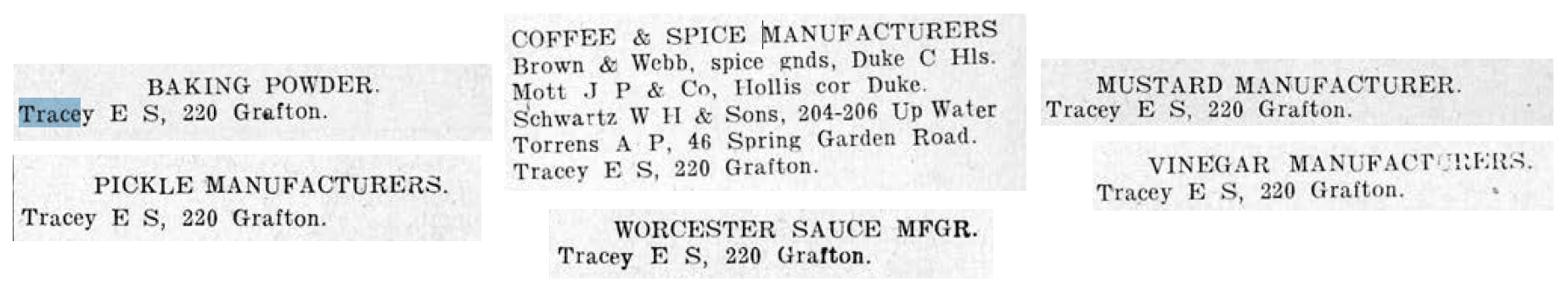

Hi folks. It's me. I hit this hard bottom. How could I not when under the heading for Pickle Manufacturers, there was but one listing:

With another quick flip through the directory, I discovered that the E. stands for Edwin, and now Edwin S. Tracey and his once local pickle factory are all I can think about. Who is Edwin S. Tracey? What's his story? Let's dive into the brine and learn about his life, his business, his time as Halifax's Temperance Inspector, and of course, his pickles.

Edwin S. Tracey

Edwin Seymour Tracey was born in Ship Harbor on January 12, 1870. His father, Edward (1845-1920), also born in Ship Harbour, made his living in numerous ways over the course of Edwin's life. Records list him as a fisherman, a ferryman, a cooper, and as an employee for Nova Scotia Car Works Ltd, just to name a few. His father also served with the 12th Regiment of the Nova Scotia Militia under Lt. Col. George Fraser in 1866. Edwin's mother, Angeline Glawson (1848-1891), also of Ship Harbour, managed their household of ten children.

The family spent the early part of Edwin's life in the Ship Harbour/Jeddore area, but by the late 1880s, Edwin had left home for new adventures. According to the 1888 Halifax city directory, he lived at 115 Upper Water Street and worked as a clerk. In subsequent directories, Edwin worked for J. R. Siteman & Co., a wholesale and retail company that dealt primarily in grocery items for both homes and stores on ships. Within three years, the entire Tracey family had moved into the city. Initially, the extended family also took up residence in the downtown core, but by at least 1894, the family had moved to 21 Bloomfield Street in Halifax's North End. Edwin may have moved to Bloomfield with them, but some resources show that he remained on Lower Water Street.

As Edwin set down roots in Halifax, he happened to meet Hattie (or Hettie) L. R. West. Hattie was born on July 11, 1864, in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia. Her father, Robert West, ran a successful retail business that dealt in everything from paint and glassware to clocks and shoes, and nearly all things in between. Exactly how she and Edwin crossed paths is uncertain, but it is possible they met as a result of some potential business dealings between Edwin and her father. However it came to be, there were certainly sparks between them. On August 22, 1893, they were married in Bridgewater by Reverend William E. Gelling.

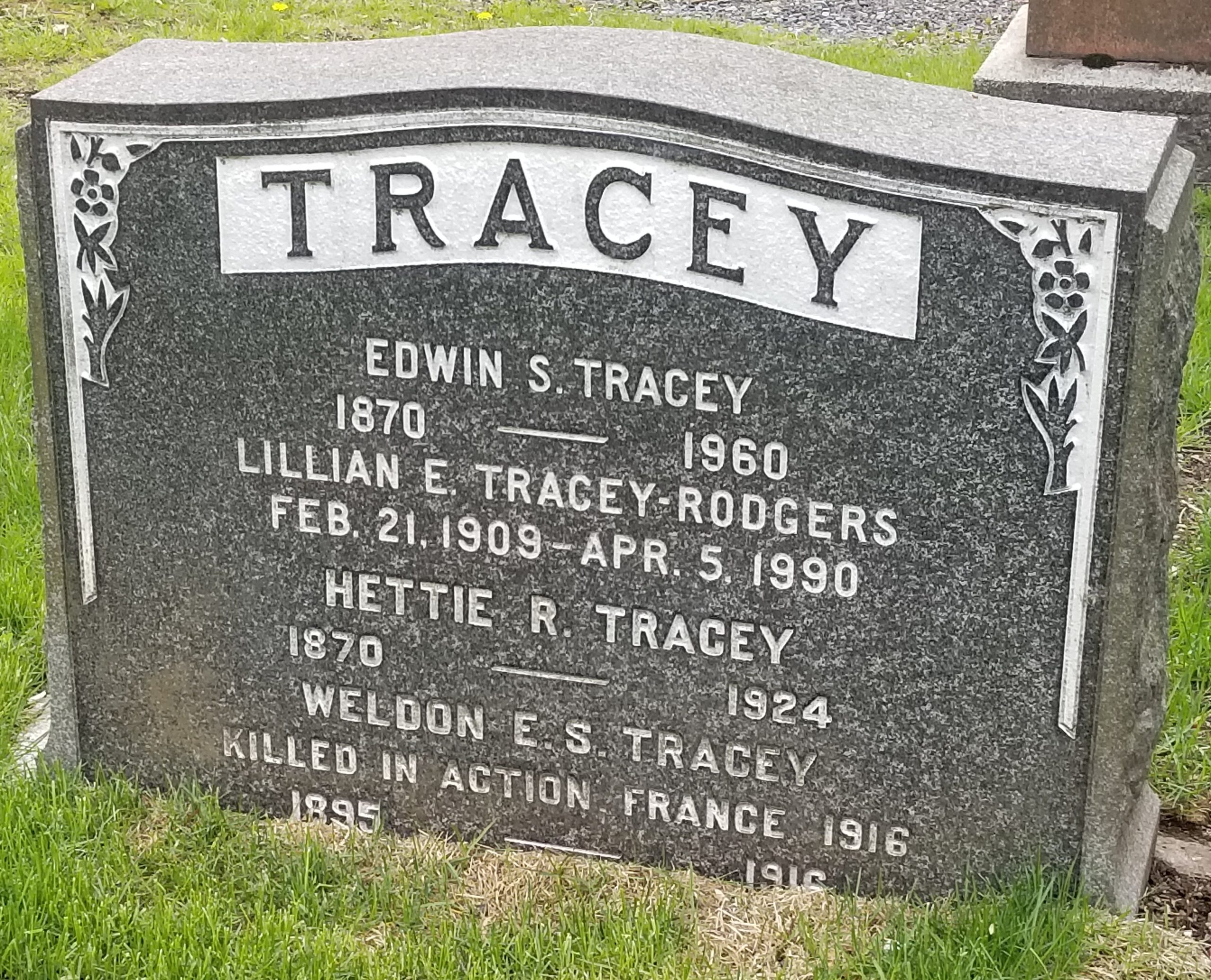

Not long after their marriage, Edwin and Hattie began trying to grow their family. Unfortunately, they suffered the loss of several children. Vernon R. B. Tracey passed away at seven months old, Cecil T. Tracey died at 14 months, and one child only referred to in records as "Tracey" passed away as they came into the world. In the midst of these tragedies, Edwin and Hattie were blessed with two children who reached adulthood: a son - Weldon, who was born in 1895 - and a daughter - Muriel Gwendolyn, who was born in 1896. The same year that Muriel was born, the couple moved into a new home a few blocks away from Edwin's family at 15 Woodill Street.

Get to the pickles already!

Edwin had always had an interest in plants and gardening. Perhaps it was this interest, coupled with having inside knowledge of the grocer trade from his time at J. R. Siteman & Co., that caused him to turn away from his position as a bookkeeper.

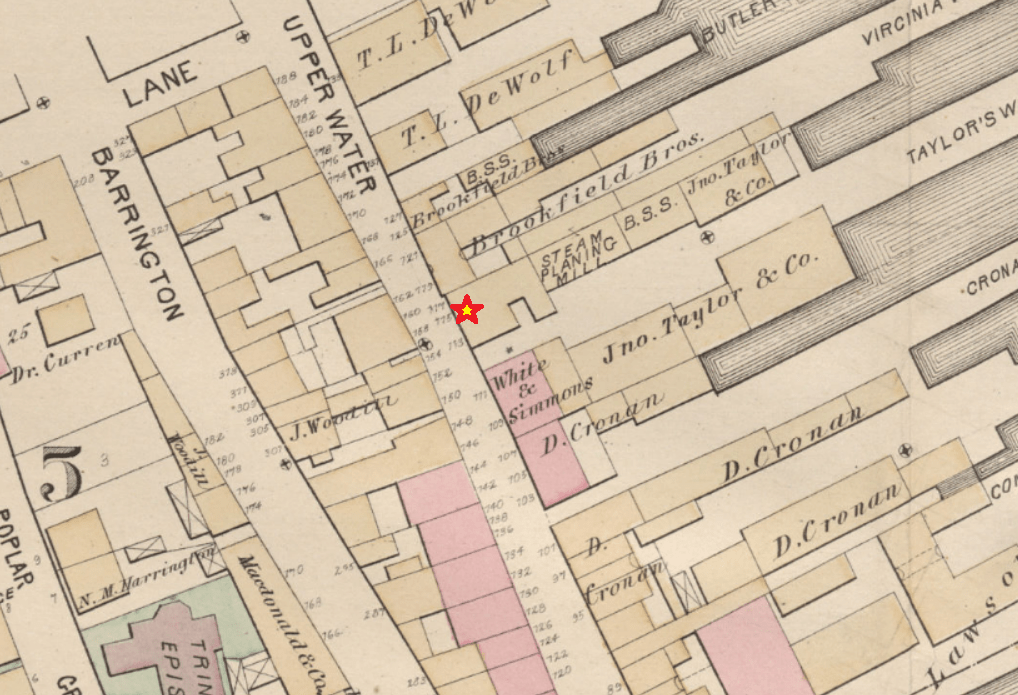

In 1888, Edwin developed a partnership with Walter Adolphus Nicolle. Just the year before, Walter had opened a grocery store at the corner of Jacob and Grafton Streets (where Duke Tower now stands). Together the men specialized in wholesale and retail groceries and alcohol sales. However, the partnership did not last long. Within two years, the listing for the store in the city directories no longer contains Walter's name. Though it might never be known exactly why the partnership dissolved, it is most likely that Walter moved to Port Mulgrave in 1899. Whatever the reason, subsequent directories show Edwin working solo for a number of years. And work he did!

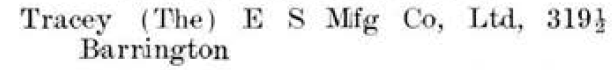

Edwin began making pickles to sell in his shop, but as it turns out, he wasn't just the local pickle man! He processed a wide variety of goods: baking powder, coffee, spices, mustards, and more! He also became well-known for his homemade syrups. By 1903, Edwin was also utilizing space at 319 1/2 Barrington Street for business purposes.

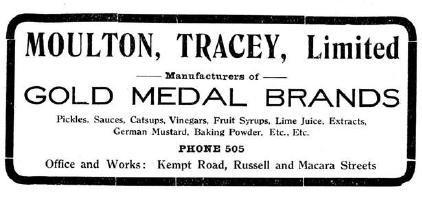

In 1912, Edwin had another business partner. The name "Moulton" appeared alongside Tracey's in city directory advertisements. The "Moulton" in Moulton, Tracey, Limited is likely to have been Abraham Moulton, a Newfoundlander who was the manager of Maritime Paint and Varnish Co. Abraham eventually went on to run the commercial merchant and shipping company Moulton A. & Co.

Moulton and Tracey moved business operations from Barrington Street to the corner of Kempt Road (now Robie Street) and Macara Street, approximately where the CTV Atlantic building stands today. It was around this time as well that advertisements in the city directories began specifically promoting "Gold Medal Brands," the label under which their items were produced. However, just like with Walter Nicolle, the partnership between the two men did not last long. By 1914 Edwin once again was the sole name attached to the business. Whether or not the men continued to work together is unknown.

Tragedy

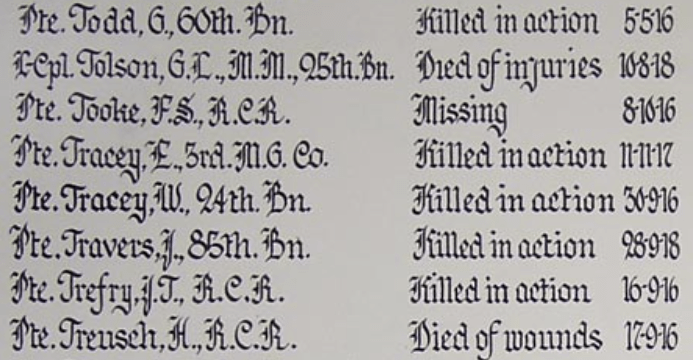

The early 1900s was a difficult time for Edwin and his family. World War I had begun, and Edwin's son Weldon joined the fight. Initially, Weldon joined the 63rd Regiment of the Halifax Rifles, but in February of 1916, he signed up for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. On his attestation papers, Weldon is described as fair-skinned with blue eyes and light brown hair; he had a vaccination mark on his left arm. Private Tracey went to Europe, but he did not make it home. He served as a part of the 24th Battalion of the Canadian Infantry, also known as the Victoria Rifles. It is believed he died while on the front line near Courcelette, France, on September 30, 1916, but his body was never recovered. To recognize his sacrifice, Weldon's name was inscribed on the Vimy Ridge Memorial in France.

In a bit of a pickle

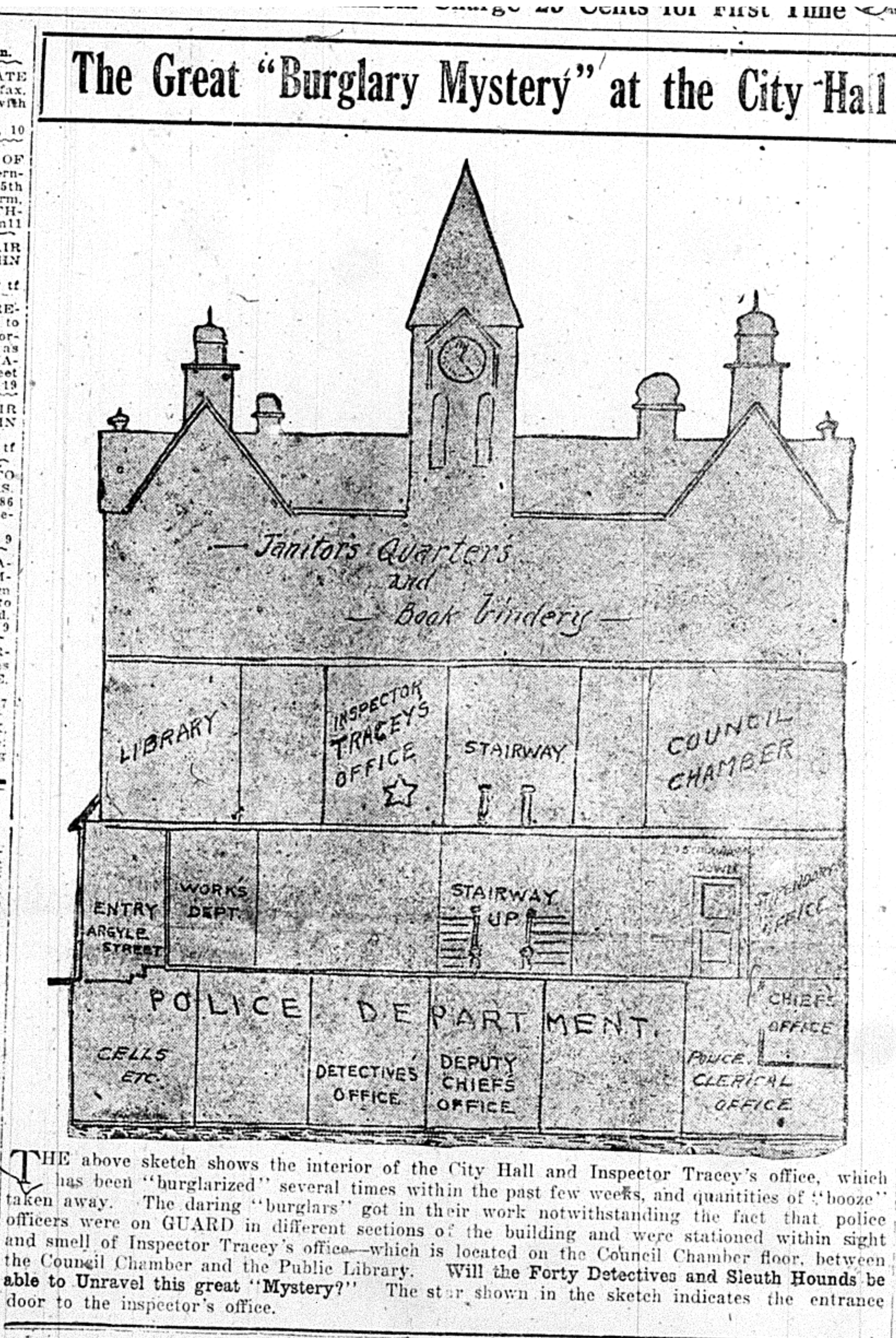

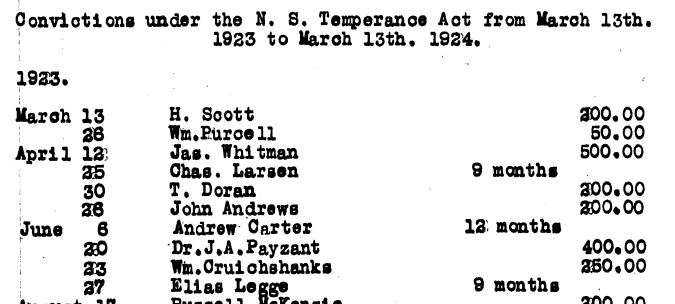

Before the war was over, Edwin made another change in his profession. In 1916 Edwin closed the E. S. Tracey factory on Kempt Road and took up a position with the city of Halifax as the Temperance Inspector, where he earned approximately $2,500 a year, or about $41,500 today. This was a particularly demanding job as during World War I, laws enforcing prohibition had been put into place. These laws came to pass partially due to pressure from the temperance movement which toted the evils of alcohol, but also due to the war itself. The restriction of alcohol was seen as an important wartime sacrifice; the grains used to distill alcohol should be diverted to feed the troops overseas. While serving as Temperance Inspector, Edwin had an office in the town hall and became responsible for confiscating alcoholic contraband.

On December 6, 1917, at 9:04 a.m., the ships Mont-Blanc and Imo collided in Halifax Harbour, causing the Halifax explosion. The Richmond district in the North End was levelled, with the surrounding areas being all but destroyed. Nearly 2,000 people were killed, and thousands more were injured. With no way to be prepared for such an unexpected tragedy, the result was absolute chaos. Halifax City Hall contained the city council and the local police, and the building became a meeting place where those in need of shelter, food, and medical supplies could gather and seek refuge.

The following day on December 7, Edwin received a telephone message to come to his office because his door was open. He came to his office at town hall to find the door partially broken, the glass window fully smashed, and the lock on the door turned from the inside. Down the hall, several other office doors also had their windows shattered, though whether this was caused by malicious intent or the explosion itself was hard to say.

Upon entering his office, Edwin found that several cases of liquor - mostly whiskey, which he had confiscated but not yet destroyed - had been taken. The building had been busy over the past twenty-four hours, and so Edwin began to ask other people if they had seen anyone taking alcohol from his office. He was told no, and that perhaps it had been taken as part of the relief effort. Edwin had his doubts but chose not to report the incident. He boarded up his office window so the remaining alcohol would be safe.

But the next day, his office was broken into yet again. This time the lock was completely smashed, and a few more cases of liquor had disappeared. This time Edwin mentioned the theft to Deputy-Mayor H. S. Colwell and proceeded to move the remaining alcohol to the janitor's apartments on the third floor. But break-ins continued to occur. On one occasion, Edwin spent the night in his office until the early hours of the morning attempting to catch the culprit, but they did not return that particular evening. All told, during the month of December 1917, Edwin's office was broken into five separate times.

Edwin had attempted to keep the thefts quiet, but in early January 1918, the Evening Mail broke the story to the public. The report underscored that the alcohol was taken from Edwin's office while the police were on guard "...day and night in various sections of the building, and within smell and sight of the inspector's office..." (Evening Mail January 9, 1918 p. 1). They also made accusations that vehicles used to transport the injured, sick, and homeless after the explosion were also used to move the stolen alcohol to different areas of the city. What's more, they made a claim that civic officials had themselves been drinking and were seen "... staggering and half-jagged among those heart-broken and nerve-shattered North-end people." The publication then demanded the names of those officers who had been on duty during the thefts, the names of the city officials who had been drunk at city hall during those first days after the explosion, and the resignation of the head of any department that was connected with the theft. The implication that the theft had perhaps been an inside job or that the city council had been directly involved did not sit well with Mayor Martin or his aldermen. In fact, so much offence was taken that Alderman H. E. MacNab put forward a motion at a council meeting to insist the Evening Mail and Halifax Herald both print retractions or face being formally charged with slander. The motion did not pass.

By mid-January 1918 an inquiry had begun to get to the bottom of what had transpired. Edwin, along with several city council members, were interviewed about their knowledge of the events. During questioning, Edwin stated that this was not the first time his office had been broken into, though the previous culprits had been caught. He also admitted that after the explosion, he did issue some bottles of liquor to the men who had been recovering the dead from the devastated area and to those who were working at the morgue. The rest of the liquor had been taken without his permission or knowledge.

The city council members who were interviewed swore to know nothing of the thefts. Alderman H. E. MacNab said the following in his report:

I have no information. I know nothing about it except what I saw in the newspapers ... my motion was not so much with regard to the stealing of booze as with regard to who were drunk around the building at that time. That is one of the most serious charges... As to the stealing of the liquor from Mr. Tracey's office, we can all see that is going to be a hard thing to get at. We will never get at who took it. It was taken when all thieves take things, in the dead of night when there was no one around to see them take it.

Investigation into the Theft of Liquor from City Hall, January 18, 1918, p. 12

MacNab was right. When all was said and done, the thief was never caught. As for the drunkenness and calls of slander: no one interviewed regarding their involvement in the crime or for being drunk in the wake of the Explosion were ever charged. The Halifax newspapers of the day never faced litigation.

It gets worse before it gets better

The early twentieth century was a rough time for Edwin. Between the loss of his son and the scandal at City Hall, he was no doubt ready for a time of peace and tranquillity. Unfortunately, that is not something he received.

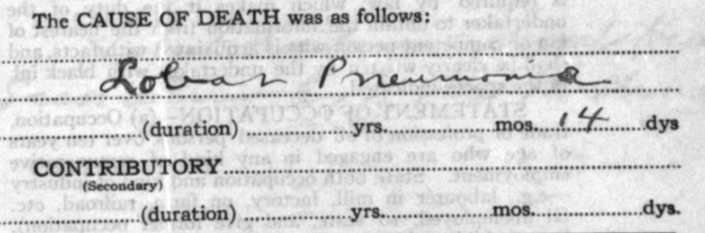

In early January 1924, Edwin's wife Hattie became sick with lobar pneumonia, which she was unable to fight off. She passed away on January 19 at fifty-four years old. Edwin, his daughter Muriel and her husband Wallace no doubt leaned heavily on each other for support during their time of grief.

With his wife now departed, Edwin did his best to move on. He continued to work as the city's Temperance Inspector until 1926/27, when he decided to turn over a new leaf.

New beginnings and full circles

Exactly why Edwin left his job as the Temperance Inspector is not truly known. Perhaps he saw the end of the temperance laws on the horizon, or perhaps he was even dismissed from the position. As he was now in his mid-fifties, maybe he was simply looking to retire. Or maybe he was just looking to do something he loved.

During his time as the Temperance Inspector, Edwin did not forget his love for plants and gardening. He became known for his beautiful flower gardens at his summer cottage in Tantallon - particularly for his dahlias. He even won awards for his blooms in local flower shows. Plants and gardens were indeed a personal passion, and so by 1927, Edwin was living his best life working as a florist.

Soon, there would be more good news. Edwin met Lillian Eileen Carroll, who lived nearby on Gottingen Street. Her father, Thomas H. Carroll, worked as a shipper for Benjamin Moore. Lillian was significantly younger than Edwin - nearly forty years his junior - but it does not appear the age difference was an issue. They were married on September 12, 1929, in St. George Anglican Church's rectory. The couple had three children together: Beryl (1930), Weldon (1931-2020), and Edwin Jr.

Edwin and his newly formed family lived their life together at 7 Woodill Street in Halifax. He continued to work as a florist and salesman until just before the start of World War II. In 1935, he pivoted back to his earlier profession and once more became the strong arm of alcohol law enforcement in Halifax when he gained employment as the Liquor Inspector. Thankfully, wartime prohibition was not in practice through the Second World War, so perhaps things were a little easier the second time around, or at least less scandalous! Edwin continued to work as the Liquor Inspector until approximately 1955, when it looks like he finally retired at 85 years old.

Well... mostly.

Keeping the family tradition and the end of a long story

Documents suggest that Edwin never truly stopped making his homemade syrups, and his interests were not lost on his children. In 1956, Edwin Jr. took up the mantle of his father and once again began making Gold Medal juices and syrups under the name E. S. Tracey Manufacturing Co. HIs son Weldon also joined in the business, helping to bottle their products, and Edwin himself lent a hand. It was a small industry run out of the family house on Woodill Street, but it was a testament to one man's passion inspiring the next generation. Unfortunately, Edwin's involvement in the business did not last long.

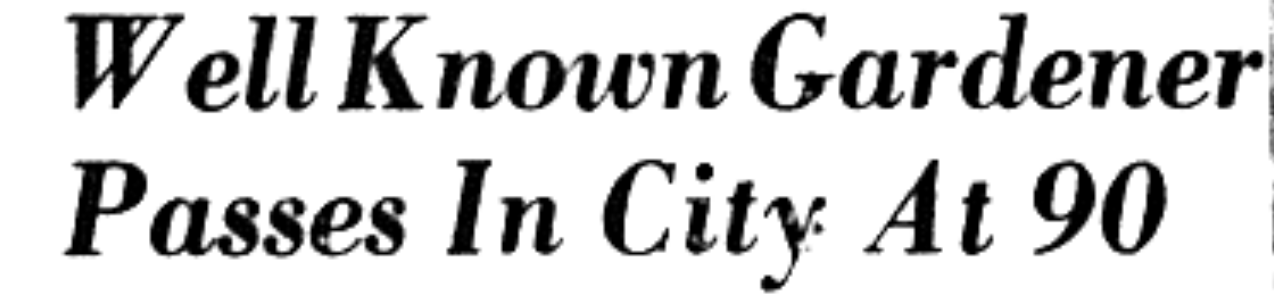

Edwin had been dealing with a string of health problems later in life. For nearly two decades, he had been fighting heart disease, and within the year of 1959-1960, he fractured his right hip and was diagnosed with prostate cancer. It was something else, however, that would ultimately end his life. In early June 1960, Edwin suffered a stroke. Approximately one week later, he passed away on June 16, 1960, at age 90.

The Finishing Lines

I started this blog looking to write a cute story about a pickle factory, but as so often happens when you throw yourself at historical research: I got a tale more complex and more intriguing than I anticipated.

In his obituary, Edwin is remembered as a prominent citizen in Halifax. He is praised for his work with his company E. S. Tracey Manufacturing, and as the liquor inspector, but he is best remembered for his beautiful flowers and garden. On his death certificate, there's no mention of his time as a liquor inspector, only that he was a syrup manufacturer and that he had been doing it for sixty years. I think this is how Edwin would have wanted to be remembered: that he lived a long full life doing the things he loved most.

Sources

Battle of the Somme Roll of Honour, opens a new window

Books of Remembrance, Halifax Public Libraries, opens a new window

Courcelette Canadian Memorial, opens a new window

Dahlia photo, Andrea Stöckel, Public Domain Pictures, opens a new window

Gold Medal Lime Juice Bottle, Etsy, opens a new window

Fenian Raids, Ancestry, opens a new window

Halifax Riflers, Government of Canada, opens a new window

Halifax City Council Meeting Minutes, Halifax Municipal Archives, March 27, 1924, opens a new window

Hettie Tracey, Nova Scotia Vital Statistics, opens a new window

Hopkins City Atlas of Halifax, Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

Inflation Calculator, opens a new window

Liquor Theft, Halifax Municipal Archives, opens a new window

Looking north toward Pier 8... Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

Pickles, Wall Paper Flare, opens a new window

Pneumonia, Johns Hopkins Medicine, opens a new window

Prohibition in Canada, the Canadian Encyclopedia, opens a new window

Weldon Tracey, Obituary, opens a new window

Special thanks to the fine folks at the Municipal Cemeteries Office, opens a new window and the Halifax Municipal Archives, opens a new window.

Add a comment to: Finding Yourself in a Bit of a Pickle: The Life of Edwin Seymour Tracey – A Brief and Not at all Definitive History