Written by Kristine, staff member, Halifax Central Library

In today’s world of air travel it’s hard to believe that only a century ago human flight was still a novelty. It’s been just a little over a hundred years since very the first short powered flights of the Wright brothers in 1903. Now at any given moment, hundreds of thousands of people are in the air across the globe.

With the outbreak of the First World War, most early flying efforts had to be put on hold or re-directed to military purposes. In 1919, with the war finally over, Atlantic Canada was a place of some important progress in aviation technology.

There were several reasons for our region to be a bit of an aeronautical “hotspot” in 1919. One factor was geography: Newfoundland is North America’s most north-easterly point and so was a natural home base for those attempting to cross the Atlantic by air.

Cape Breton was also the part-time home to Alexander Graham Bell. Although Bell is most well-known for inventing the telephone, he was an important pioneer in aviation research. Different methods of flight were among the many projects he worked on at Baddeck from the 1890s until his death in 1922.

The Atlantic Air Race

In 1919, with the need for military flight applications behind them, engineers and pilots could once again turn their attention to improving the capacity and range of their flying machines for peaceful goals. One of the most sought-after achievements was a non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

In the spring of 1919, Newfoundland became the home base for several crews attempting to be the first to achieve this feat. Many of them were flying decommissioned WWI bombers that had to be brought over from England by ship. The incentive was large—a prize of £10,000, which had been first offered in 1913 by Lord Northcliffe, owner of the Daily Mail newspaper in England. In today’s currency that would amount to something like $800,000.00 Canadian dollars.

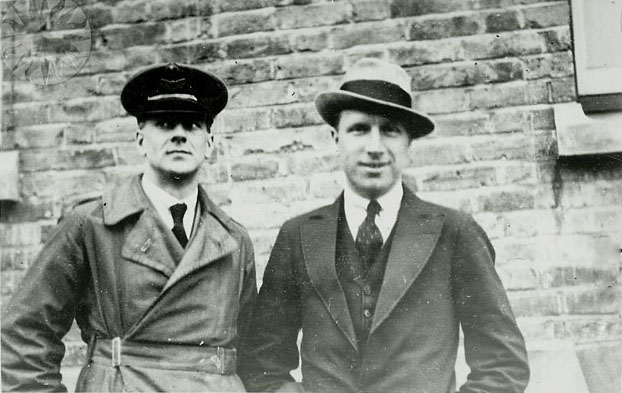

Great excitement surrounded St. John’s and neighbouring towns chosen as airfields. Many Newfoundlanders had never seen an airplane before—now they were at the centre of an international air race. 2 attempts had already ended in crashes before the departure of British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown on June 14.

With Alcock as pilot and Brown navigating by the sun and stars, the 2 men flew a Vickers Vimy biplane into what became a somewhat terrifying night. Only an hour after takeoff, the plane’s electrical generator was damaged, leaving the crew with no radio contact for the rest of the flight.

Weather conditions, although good at the start, became foggy and cloudy during the night. At one point the clouds were so dense that they could no longer tell which way was up, and the plane narrowly avoided going into the ocean. Freezing temperatures were extremely uncomfortable for the 2 men flying in an open cockpit. The cold also caused ice on the wings and engine troubles near the end of the journey.

Despite the challenges, Alcock and Brown made it through the 16.5 hour night flight. They became the first to complete a non-stop Atlantic air crossing when they landed in a boggy area near Clifden, Ireland on the morning of June 15.

To learn more about Eastern Canada’s role in the history of aviation across the Atlantic, try Gavin Will’s book The Big Hop, which conveys the sense of excitement of the time and also has excellent reproductions of photographs of the aviators who strove to push flying farther and faster than ever.

Flying the mail

One of the Atlantic region’s “firsts” happened through an accident which occurred in July of 1919: the crash landing of a plane in Parrsboro, Nova Scotia.

The Handley Page V/1500 Atlantic had been built for use as a bomber in the First World War, although the war ended before it went into active service. In 1919 the Atlantic was shipped from England to Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, for an attempt at the non-stop Atlantic crossing by Admiral Mark Kerr and his crew.

When Alcock and Brown beat them to the punch, Admiral Kerr accepted an invitation to tour the United States with the Atlantic. They departed for New York on July 4, 1919, and at 1:00 AM on July 5 the Atlantic was forced to make an emergency landing at Parrsboro, Nova Scotia.

Although the crew were unhurt, the plane was severely damaged during the landing. The Atlantic remained at Parrsboro for repairs until October 9, 1919, when it finally finished the journey to New York.

This journey was especially significant because it carried the first ever air mail from Nova Scotia to the United States. This was just a few months after the first Canada-U.S.A. international airmail had been delivered on March 3, 1919, from Vancouver to Seattle.

The landing of the Atlantic was a large event in the life of the community of Parrsboro; a plaque in the town marks the event and plans are in the works for a reconstruction and memorial festival later this year.

On September 24 of 1919 another airmail “first” took place. This was the delivery of airmail to PEI arrived on a flight from Truro to Charlottetown on a Curtiss JN-4 biplane. The flight was organized by the newly formed Devere Aviation Company to promote their aerodrome and school. The return flight carried a letter from the Postmaster of Charlottetown to the Postmaster of Truro that remarked how mail had arrived in one day that would have normally taken 1 or 2 weeks by conventional post.

Bell at Baddeck

Aviation was one of Alexander Graham Bell’s chief interests in the later part of his life. He and his associates in the Aerial Experiment Association spent much of their time at Baddeck, where they accomplished the first powered flight in Canada with their Silver Dart plane in 1909.

In 1919, after a wartime hiatus, Bell’s research returned to a related project, the “flying boat” or hydrofoil, which he had first developed in 1911. Hydrofoils use plates to push the craft above water the same way airplane wings function in the air, and Bell’s research had impact both on marine and air craft design.

On September 9, 1919, Bell’s hydrofoil HD-4 set a world record water speed of 114.04 km/h crossing the Bras d’Or lake. That speed was more than double the speed of the fastest conventional boats.

To learn more about Alexander Graham Bell’s work in aviation try Terrance W. MacDonald’s 2017 book Firsts in Flight: Alexander Graham Bell and his Innovative Airplanes.

Find more in our Local History collection

Daring Lady Flyers: Canadian women in the early days of aviation

Add a comment to: 1919: A Year of Flying Firsts